This article is an edited version of a talk I gave, in collaboration with David Cant, to the Cragg Vale History Group on 17th April 2025 at St John’s in the Wilderness Church. In the first half of our talk, David gave an overview of the history of hill farming in the Calder Valley and an introduction to W.B. Crump’s invaluable 1951 book, The Little Hill Farm (hence the overall title of our talk, ‘The Little Hill Farm, 70 years On’). For my section of the talk, I focussed specifically on the farms in Cragg Vale, telling their story from the 1940s onwards.

I have always admired the farms of the upper Calder Valley, and W.B. Crump’s 1951 book The Little Hill Farm is such a marvellous testament to them. In this article I will give an account of the state of Cragg Vale’s little hill farms towards the end of Crump’s life, in the 1940s. This was a little before his book was published, but was actually long after he had conducted most of his research around 30 years before. I will also talk a little about the changes in the post-war period.

Crump himself looked to the future in the final paragraphs of his book: ‘Doctrines change, customs die out, but the little hill farm…plays its part in the agricultural economy of the country.’ But he bemoaned how the Ministry of Agriculture encouraged big farms and big fields while, in his words, ‘despising and neglecting’ the little hill farms. Sadly, some would say nothing has changed, and I can only imagine what Crump would make of how things have gone since.

As Crump ruefully observed when recollecting giving his first lecture on the subject in 1913, the audience ‘took great pleasure in extending my knowledge of local farming.’ As I invited my audience to at the talk, readers here should feel free to take such pleasure in extending my knowledge, as I am always ready to learn, especially as I hail neither from a farming background nor from Cragg Vale. Please leave any comments below, or email on pauljamesknights[at]gmail[dot]com

Here to start is a typical little hill farm, Wood Top.

It seems, from the caption that accompanies it in the Pennine Horizons Digital Archive, to be inhabited by the Wilkinson family. It is not dated but it looks to be perhaps early 20th century, when Crump would have been roaming the hills, so perhaps he passed this way and spoke to the Wilkinsons.

Crump mentions a few places in Cragg Vale in his book, but he seems to have been particularly fond of visiting the Greenwood family at Broadhead End. Here it is today.

Through Crump’s account of visiting between 1908 and 1912, we learn that the Greenwoods rented 53 acres for a low rent of £30, and kept six cattle, some pigs, and enough poultry to produce 8,000 eggs each year.

Crump remembered the ‘musical hum’ of the milk separator, with the skim milk fed to the pigs and calves. Mrs Greenwood made 30 pounds of butter a week, selling it for 1s 5d per pound around Mytholmroyd. The large meadow, the six-day-work meadow, was limed every year with five tons of lime, hauled up from Mytholmroyd Station.

Crump also recounts how, on June 24th 1908, St John’s Day, two Irish mowers began work in the ‘six-daywork’ meadow in front of the house. Mr Greenwood and his father-in-law would shake out the swaths to dry and carry ‘burdens’ of hay, each weighing 3–4 stone, to the 200-cubic-yard hay mow (loft), working from 10 o’clock in the morning to 8 o’clock in the evening, until the mow was full.

Crump explains that a daywork was roughly two-thirds of an acre, derived from the local perch of seven yards. This accords with his description of the meadow in question as the ‘six-daywork’, since its area is recorded on the 1907 Ordnance Survey map as 3.686 acres, making it just a shade under six days’ work.

Crump records that the two mowers expected to scythe the meadow in two days, meaning they would each cover more than the two-thirds of an acre of a daywork each day – in fact around 0.92 acres. Their earnings were 5s per daywork, so they likely earned around 7s 6d per day, which is around £40–£45 in today’s money. In addition, the Greenwoods, as was traditional, supplied them with accommodation and five meals a day.

So we’ve seen Wood Top and Broadhead End, but these little hill farms are liberally scattered across the ‘tops’. Crump quotes, as everyone does, Defoe’s 18th-century observation that the ‘sides of the hills…were spread with houses, and that very thick’.

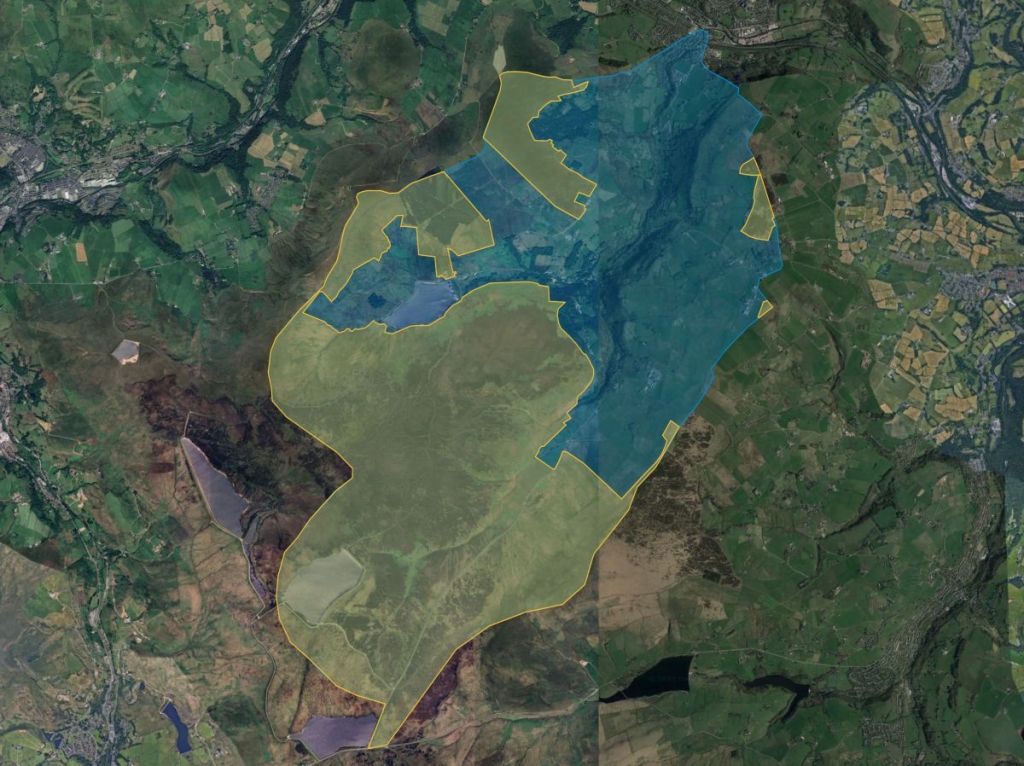

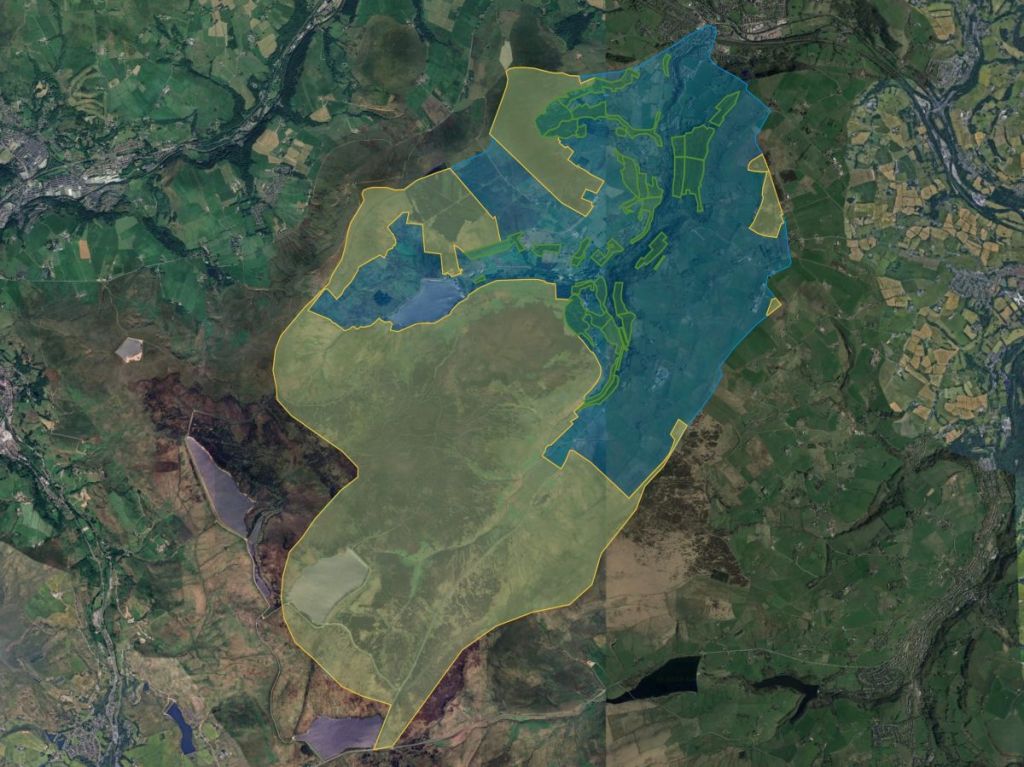

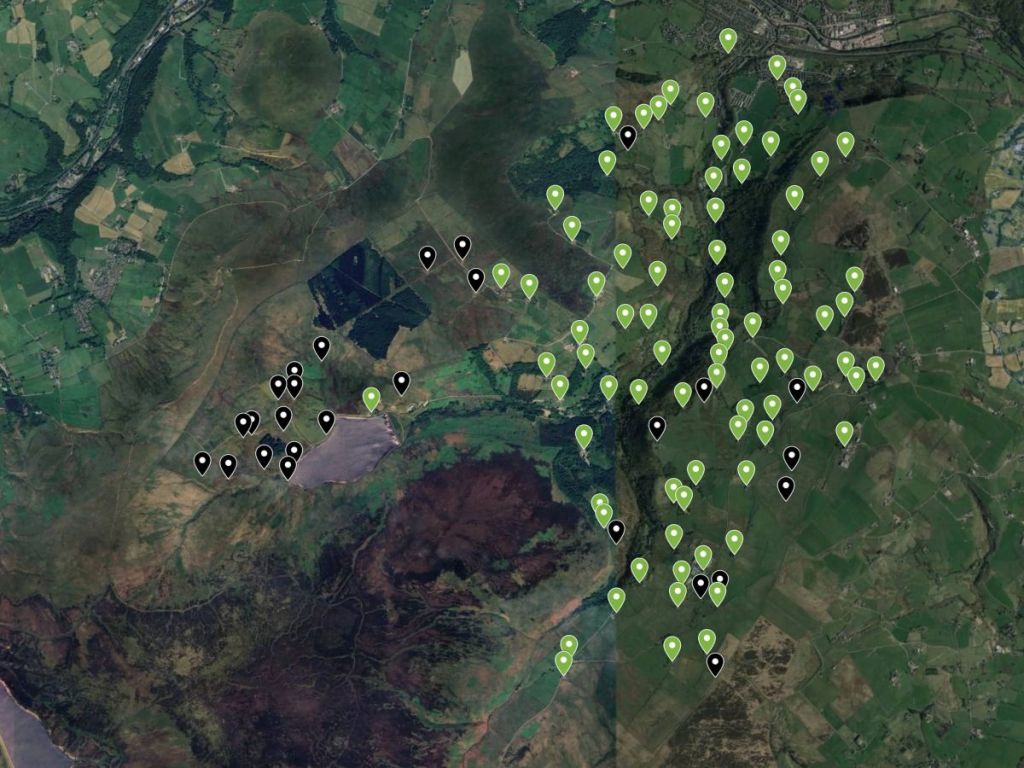

How thick? Well, to put what came after the Second World War in context, I wanted to know how many little hill farms there were originally, so I mapped all the farms there ever were in Cragg Vale. Poring over the historic OS maps, I found 114…

…so Defoe was not wrong – the hills were spread very thickly with houses, as this figure does not even include any cottages and other dwellings beside farmhouses. In fact, the farms seem to be at such a density that it appears they must have had only a very small parcel of land each. The 1793 General View of the Agriculture of the West Riding mentions that each homestead has ‘a sufficient quantity of meadow and of pasture for the support of a horse and a cow, with now and then a corn field’.

Let’s work it out what counted as sufficient. The area I mapped was bounded by the catchment of Cragg Vale’s river, called Turvin Clough in its upper reaches, then called Cragg Brook and finally Elphin Brook in its final stretch before it joins the Calder. This five-and-a-half-mile-long river drains an area of 6202 acres.

But much of this is moorland, and while many farms had rights to graze stock upon the open moor…

…this doesn’t allow us to work out the average size of a holding in terms of how much enclosed pasture and meadow they each had. So we need to subtract the 3550 acres, or 57%, of the catchment which is moor, here shaded orange.

Not only that, but Cragg Vale is a quite a wooded valley…

…so we also need to subtract these woodlands (although stock is sometimes grazed in them, and winter fodder in the form of holly was harvested from them). There are 39 named woodlands in Cragg Vale, so I mapped those as well, shaded green, and divided into their individually named compartments.

Here’s a closer look without the other layers of the catchment and the moors. I mapped their extent in the late 19th century, but you can see that since then they have greatly expanded, although they have mostly expanded into areas which were never fully improved into meadow and pasture, judging by the shading given these areas on the old OS maps.

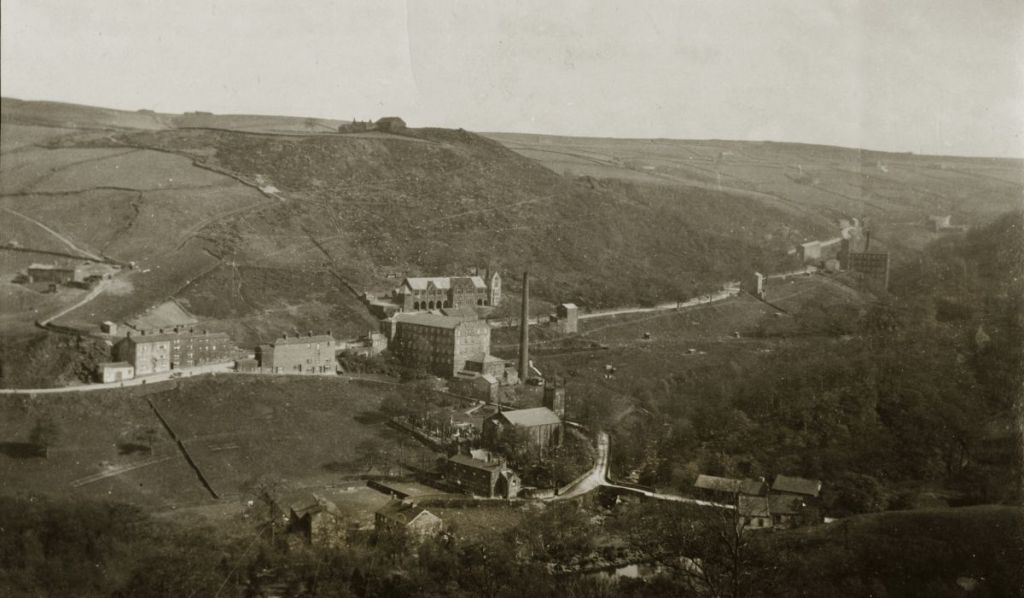

Here is an example under Bank Top, which looms darkly up on the skyline. Bank Top Wood, which wraps around the hillside under the farm, appears to be quite denuded at this time, but it has since climbed back up the hillside, also also spread across it, swaddling Marshaw Bank on the left, and linking up with Deacon Hill Wood, which is just out of shot.

But still, even with all this woodland, it only amounted to 326 acres in the 19th century, or 5.2% of the catchment. (It might be a little more because of the way the online area calculator I used deals with slopes, but let’s go with this figure.) This leaves 2326 acres, or 37.5%, as ‘pleasant and profitable greensward’. That’s all the remaining blue.

Taking the 114 farms and dividing these 2326 acres between them gives an average of 20 acres per farm.

I have done this exercise, rather more roughly, for the whole of the five townships of Erringden, Wadsworth, Heptonstall, Stansfield and Langfield and their 575 farms, and it came out as 21 acres each, so it is comparable to just Cragg Vale.

Now this might seem rough and ready, but we have some official records with which to compare this calculation, in the form of the National Farm Survey: between 1941–44, inspectors were sent to all 300,000 farms in the country, and detailed returns were filled out on every aspect of each farm’s operations. Most of the visits in Cragg Vale were made in 1943, with some in ’42 and some in ’44. Heroic members of the Hebden Bridge Local History Society went to the National Archives at Kew some years ago and photographed all of these records for Calderdale. For the 85 Cragg Vale farms for which there are returns, the range of their holding size is between three and 80 acres, with the mean at 17 acres and the median at 15.

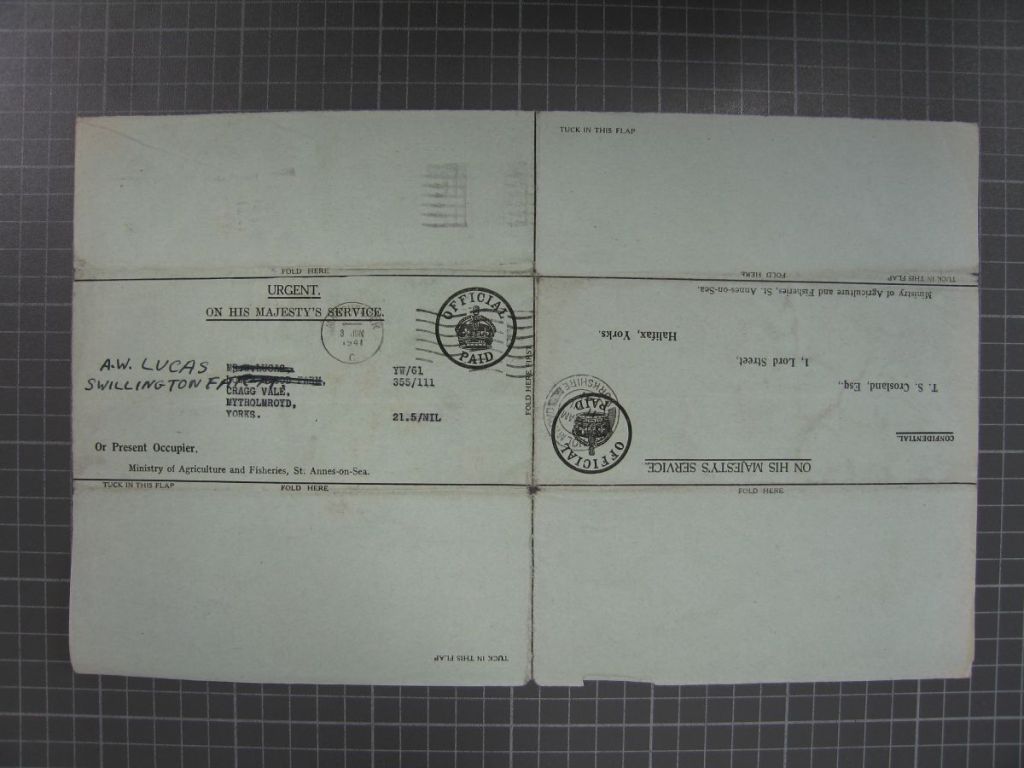

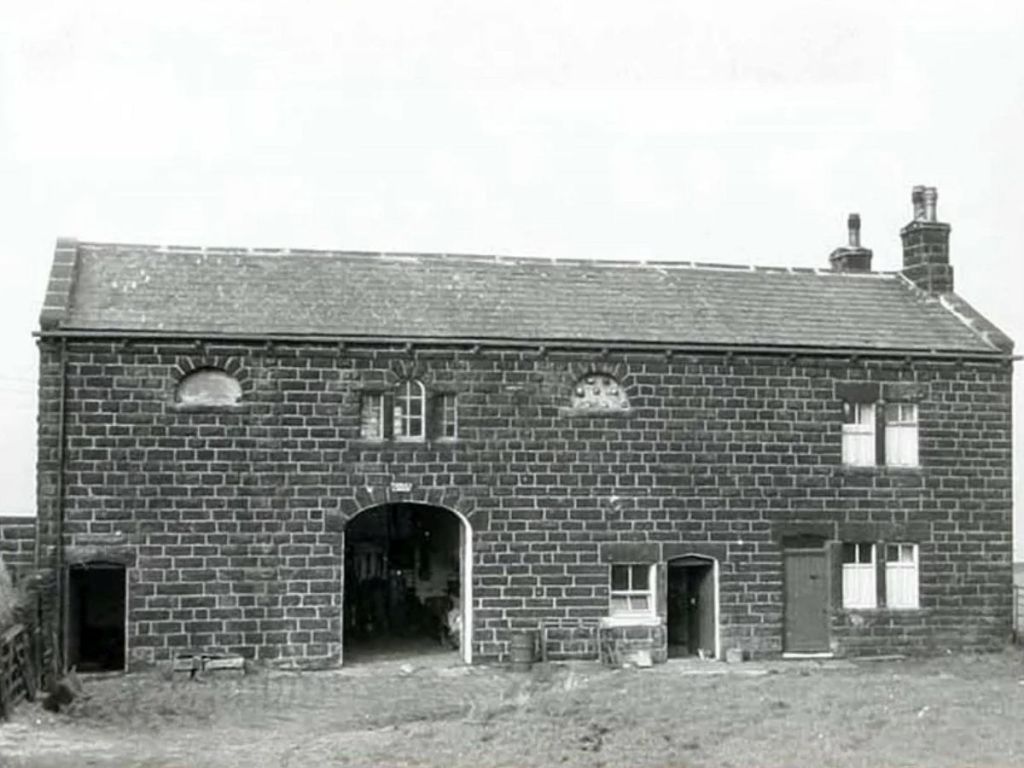

Let’s take Swillington, photographed here in the 1980s. I’ve picked it as a first example since it’s a fairly typical Cragg Vale little hill farm.

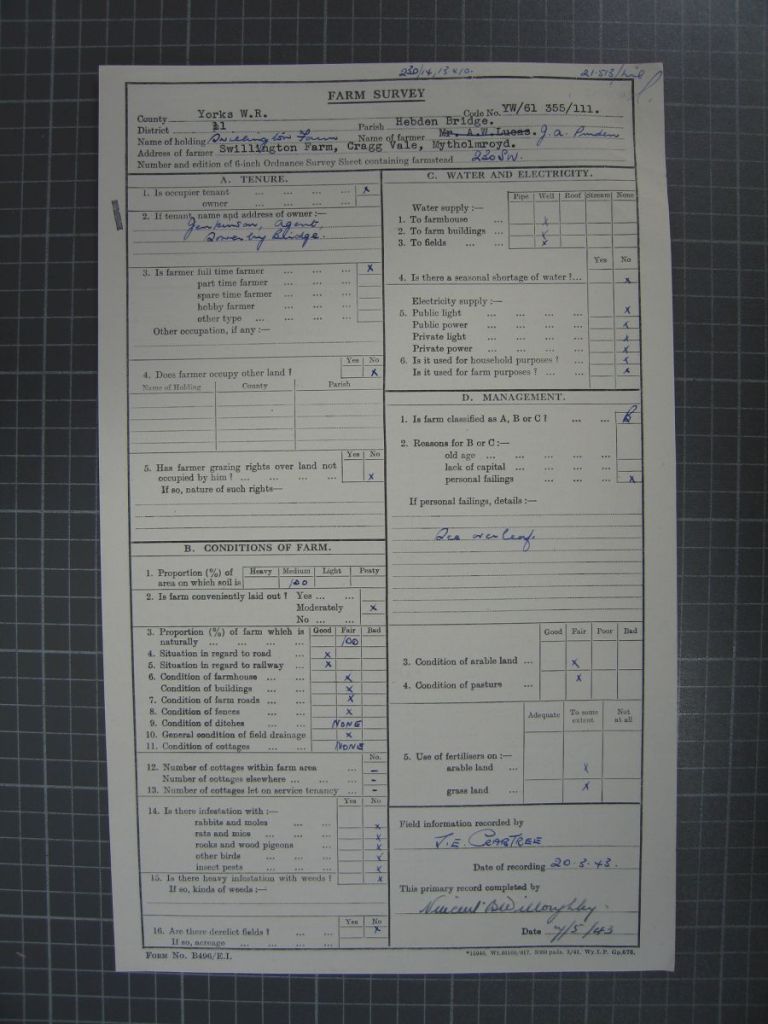

Here is the primary return of the National Farm Survey, which tells us that Swillington is farmed full time by a tenant farmer whose name I cannot quite read…

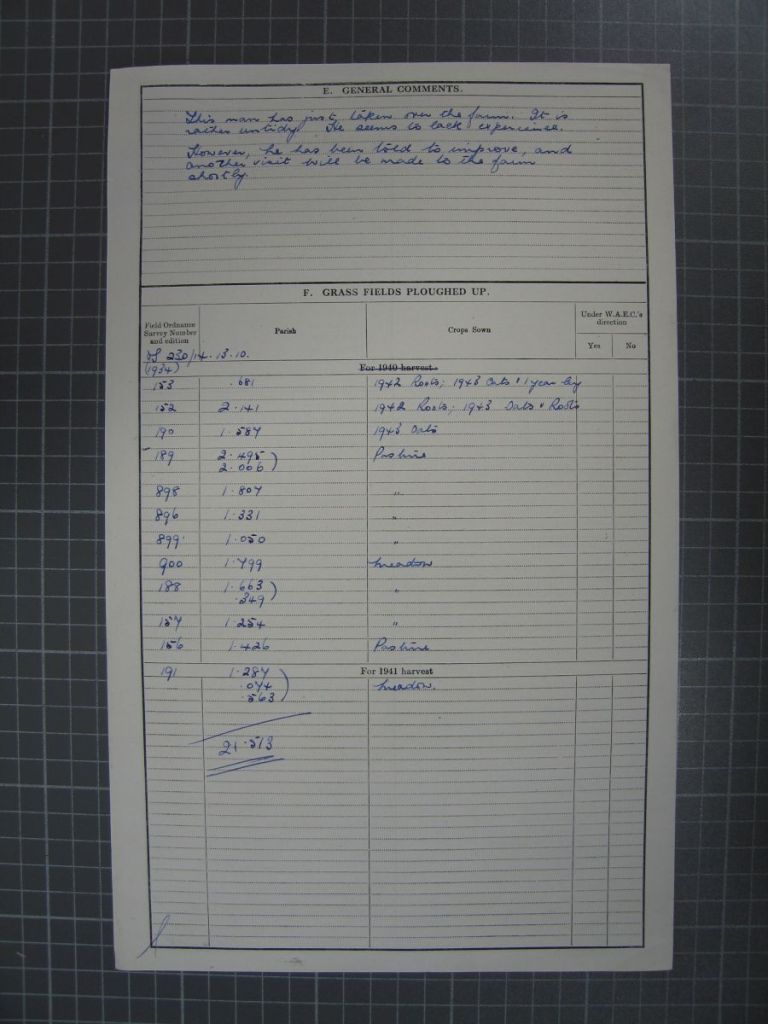

…and it has 21 acres. Every individual field is listed with a number that can be linked to the 25-inch OS maps, and what that field is used for; mostly pasture and meadow, but with some roots and oats.

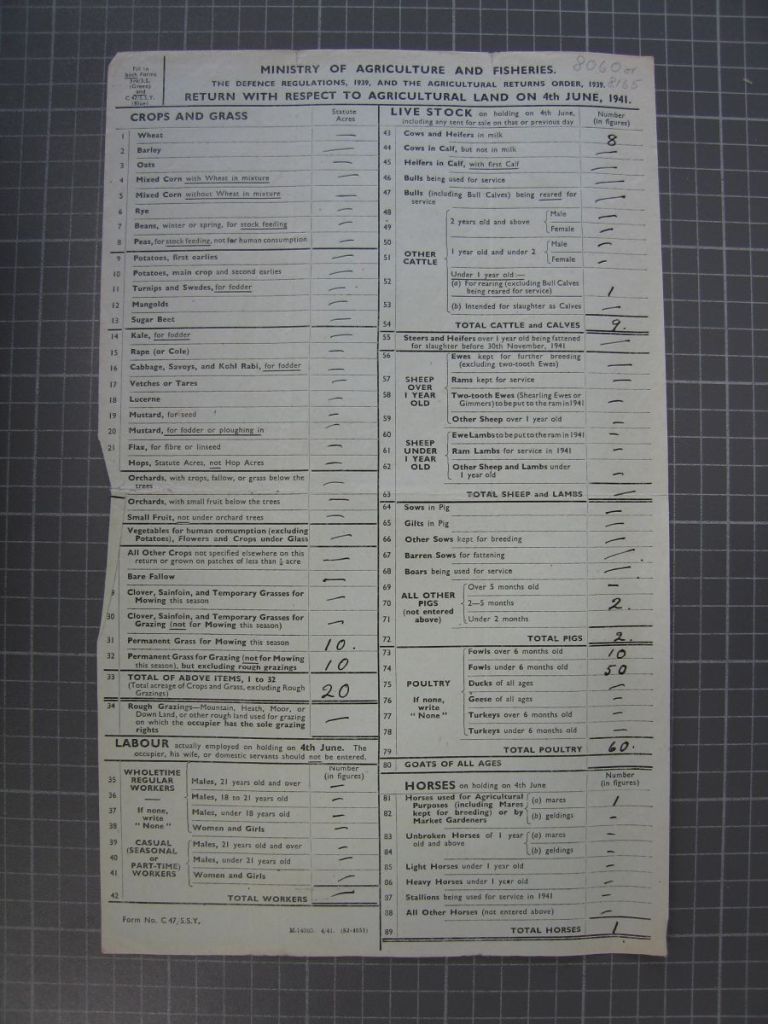

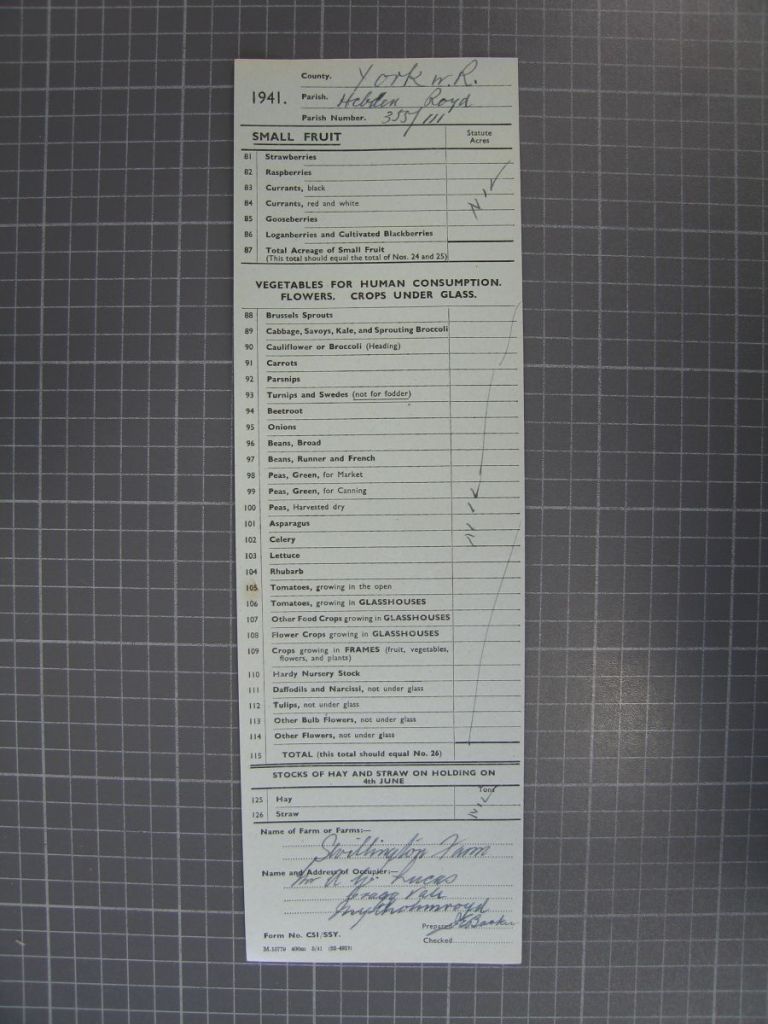

The census return, which was sent to an AW Lucas…

…tells us the that there are nine cattle, no sheep, two pigs, 60 poultry and one horse.

The horticultural return records a nil result, as almost all farms of the upper Calder Valley did.

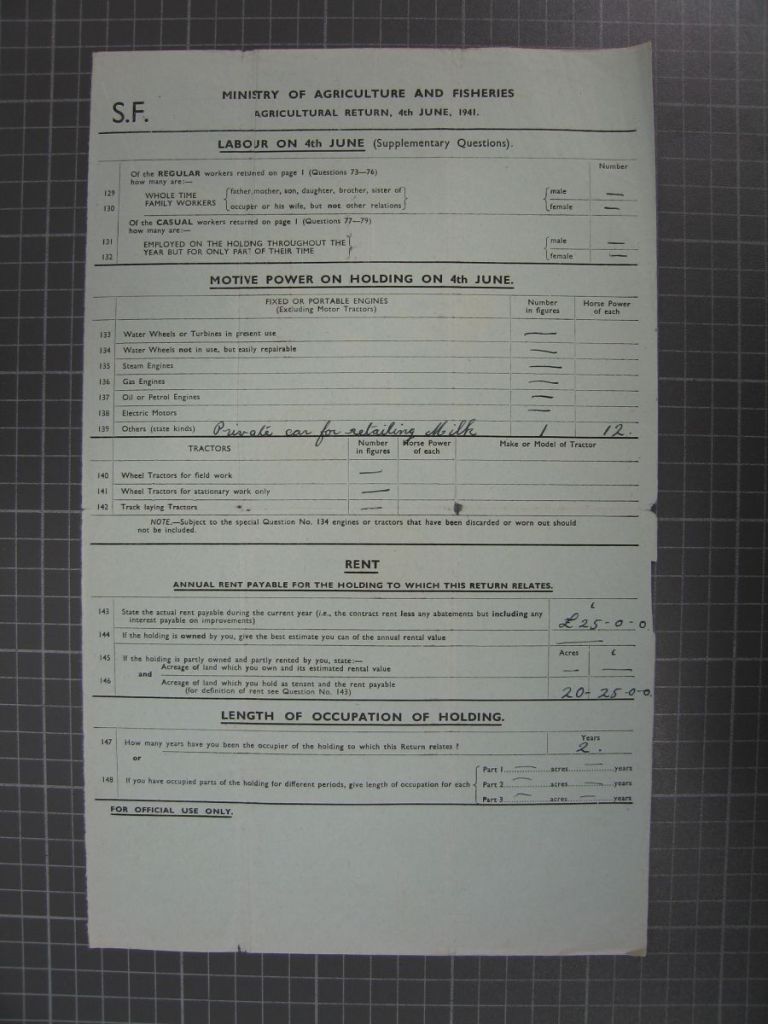

And the supplementary return…

…tells us no extra labour is employed; there is no tractor but there is a car for milk retailing; that the rent is £25; and that the farmer has been there for two years.

Here is Swillington a few winters ago. To my knowledge it is no longer a working farm as such, and in this it is also typical.

Now there is a lot of information in here; I could tell you about all sorts of things for each individual farm, like Hollin Hey here, which was labelled as Little Hollin Hey on the returns…

…but what I have picked out for analysis is the four main types of stock: cattle, sheep, pigs and poultry. I’ll take us through those with example farms to build up a picture of Cragg Vale’s little hill farms in the 1940s.

Here’s Waterstalls, for example, which was tenanted by a Mr Huntley.

Now there is a section of the primary return labelled ‘If personal failings, detail’. That is, personal failings of the farmer that might prevent them from increasing production on their farm, which was the point of the exercise. I’ll mention a few of these, but I do this to reflect on how pompous the main inspector, Mr Crabtree, was and how unpleasant it must have been to have him snooping around your farm. He did not, for instance, think much of Mr Huntley, remarking ‘This man does not seem interested in his land. Seems to fancy pet dogs and goats’. Well, whether this was true or not, neither goats nor dogs were enumerated on the survey, but cattle were, and Mr Huntley’s herd size is at the lower end of the range, with five. The smallest herd sizes were at Sandy Pickle and Marshaw Bridge, which each had two.

The other Hollin Hey, or Great Hollin Hey as it was labelled on the census return, was at the higher end, with 27.

The highest was actually at Low Bank, with 35. Of the 85 Cragg Vale farms in the survey, 52 kept cattle, so there were still 29 with none, although some of these farms were vacant. The typical herd size is around nine cattle, such as that kept by Mr Benfield at Bent Close.

Now onto pigs. Here’s Upper Lumb, where full-time farmer and farm owner Mr E Lumb kept one pig.

Whereas at Hoo Hole, full-time farmer-owners Messers E & A Lumb had 12 pigs.

Up above Hoo Hole (down at the bottom), was Plane Tree (on the left), which was actually farmed from Hollock Lee (on the right) by tenant Eric Ingham, who was branded by Mr Crabtree ‘very careless and had no ambition’. Plane Tree was more average, with five pigs.

Twenty-three farms kept pigs. Pig numbers were generally low, with most farms keeping just a few animals. The median and most common number of pigs was two. The mean was five, but this was influenced by a few larger pig holdings.

Now for poultry. High Green, which was farmed from Lower Lumb by Mr Baker, had 30 poultry. (Where I wish I could use a photograph by the renowned architectural historian Christopher Stell, which I unfortunately cannot reproduce here as I don’t have permission, I shall underline the farm name, and if you click on it a new tab will open on the Historic England website.)

And Turkey Lodge, which you’ll recognise as the oldest-looking building at The Craggs Country Business Park, had 26. This farm is unusual in that the named farmer is a woman, Miss L Easton. She was a tenant, and worked as a British Restaurant helper, so only farmed part time. Mr Crabtree was unimpressed, branding her ‘very stupid and obstinate’ and noting, with barely disguised glee, that ‘this lady has been given notice to quit by the agent’.

(I won’t say anything about the owners of the tenanted farms, as I haven’t spotted an interesting pattern, with some being local, as in the case of Turkey Lodge where the owner lives in Sowerby Bridge, and others not.)

As I said, Mr Baker farmed High Green from Lower Lumb, and down there, he had a poultry flock numbering 215.

At the very upper end of the scale, Stannery End has a flock of 1225…

…but this is an outlier, as is Elphaborough Hall, which is listed as having 77100, and that is not counting Thornber’s operation either, which is not included in the survey.

Fifty-nine farms kept poultry. The most typical flock size was around 50–60. E & A Lumb, for example, kept 50 at Dean Hey…

…but this was in addition to their 100 at Hoo Hole.

Now horses. Spare-time tenant farmer James Clarke, who before the war had made his living with poultry and pigs until this was no longer viable and he had to go to work as a warehouseman, had one horse at Lower Cragg to get around his 13 acres and tend to his nine cattle.

Fred Bainbridge of Lark Hall had a large holding…

…encompassing Broad Fold…

…and Sykes Gate…

…so he had two horses. But over half – 35 of the 63 farmers – made do without a horse.

And finally sheep.

Only 11 of the 85 farms kept sheep. Flock sizes varied widely. John Ormerod at Kirby Cote only kept nine…

…whereas there was a flock of 213 at Hill Top…

…which was farmed from Old Cragg Hall by JW Sutcliffe. The median flock size was 31, while the mean was 56. The larger flocks increased the mean, so the median gives a better picture of a typical flock.

Now I know you’re wondering about the most obvious livestock that I’ve missed out.

But I have to say that no alpacas appear on the records in the 1940s, though these at Far Moorside wanted to be counted as I walked past.

You’ll have gathered the picture as I went along that there was a mixture of owners and tenants, full-time and part-time farmers. Twenty-eight farms were occupied by their owners, as Mr A Butler did at Old House (or Olde House as it is called today)…

…and 31 were occupied by tenants, like J Cawkwell at Catherine House.

Thirty-two farmers described themselves as full time, like J Haslam at Pied Well, or Plodwell as it was labelled.

Poor Mr Haslam’s ‘personal failing’, as judged by the inspector, was ‘old age’. But he did charitably mention another disadvantage suffered by the farmer: ‘land full of rock’.

While 32 farmers were full time, 25 described themselves as part time, like Joe Hill at Higher House…

…who was otherwise a gamekeeper, albeit one that ‘lacked ambition’, although quite what ambition Mr Crabtree would have approved of is unclear.

And there were quite a number of farms that were farmed from other farms. Folly Hall (top), for example, was farmed from Cob Castle (bottom).

Now I’ll explore what has happened since Crump’s death and the publication of his book in the early 1950s. It is evident that not only are not all of those original 114 farms still standing today, but many were gone even by the time Crump was exploring the district. Indeed, 20 of them were. Thirteen of these were in The Withens, and were abandoned when Withens Clough Reservoir was built. Pasture Top was one of them.

Six more, scattered across the area, were also gone, like Windy Harbour, of which only a few wrinkles in the ground remain.

Six more fell into dereliction in the first half of the 20th century, including Blaithe Royd, Law Hill and Bank Top, whose foundations can still be seen in the fields beside the Sunderland Pasture plantation, and Red Dikes, where gamekeeper Tommy Ormerod was keeping 11 cattle, 45 sheep and 14 poultry in 1944…

…before leaving in 1947. Nearly 80 winters later, its roofless, but much of it still stands.

Deacon Hill followed some time after Edward Beattie left:

Here it is today:

Together with the recent demise of Bank Top, this brings the total to have disappeared or be in a state of dereliction to 28, or 23% of the 114.

But it might have been much worse. As recently as the late-1970s, farms were still being abandoned, neglected and falling into dereliction. Christopher Stell photographed Higher Cragg with its roof collapsing in 1961, and Ralph Cross captured a windowless Bell House in 1957. Both are inhabited today.

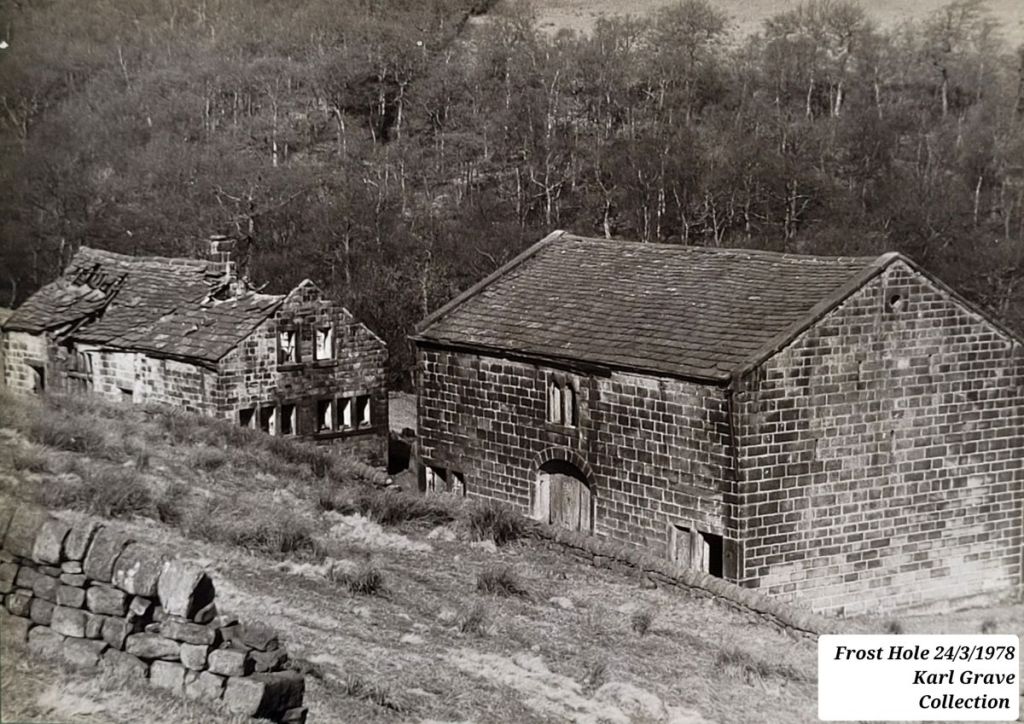

And we have Karl Grave to thank for a superb collection of images of the abandoned farms of the late 1970s and early 1980s, in a project he undertook for the Hebden Bridge Camera Club. Here is a selection of the many farms he photographed, all of which were rescued…

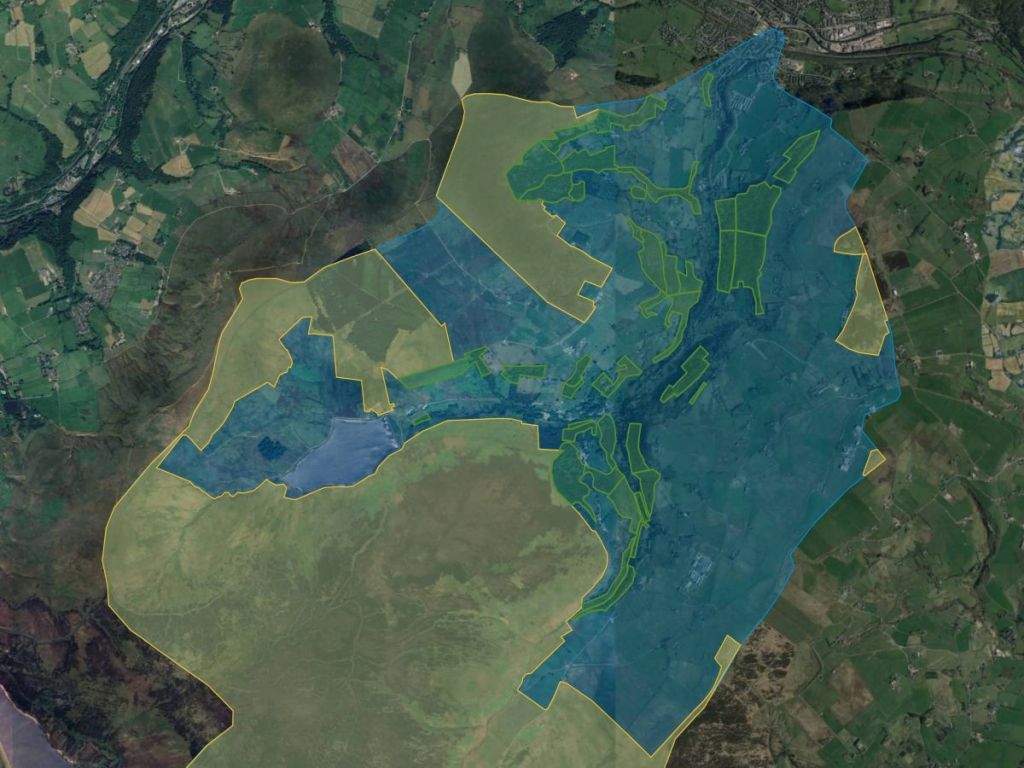

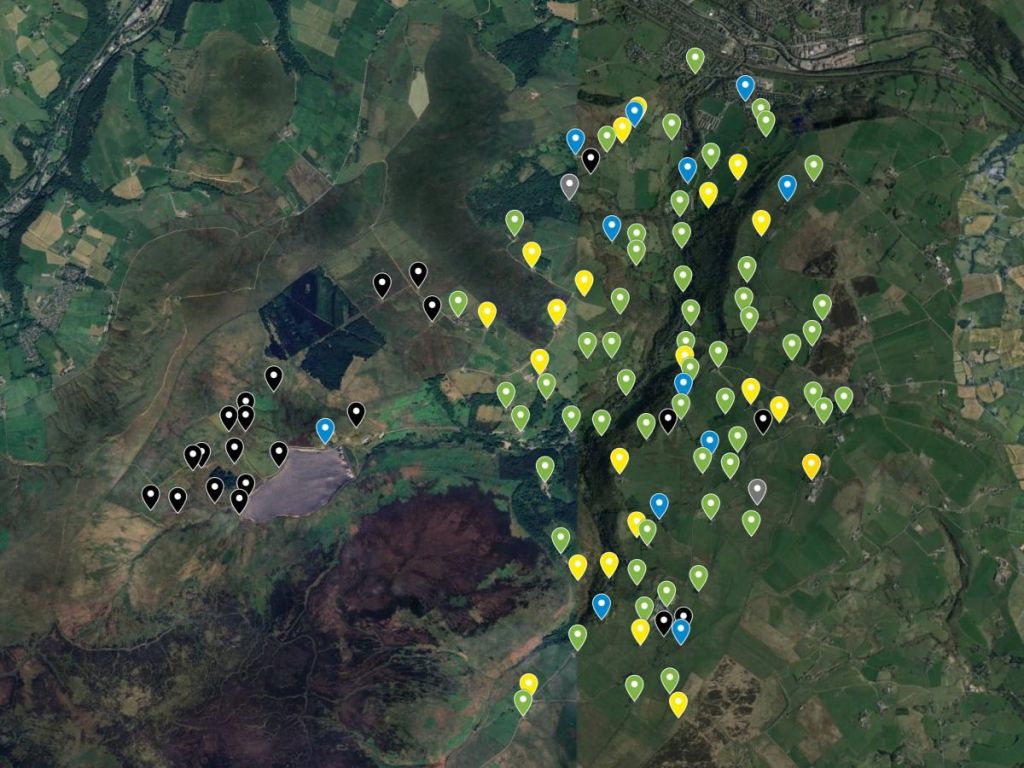

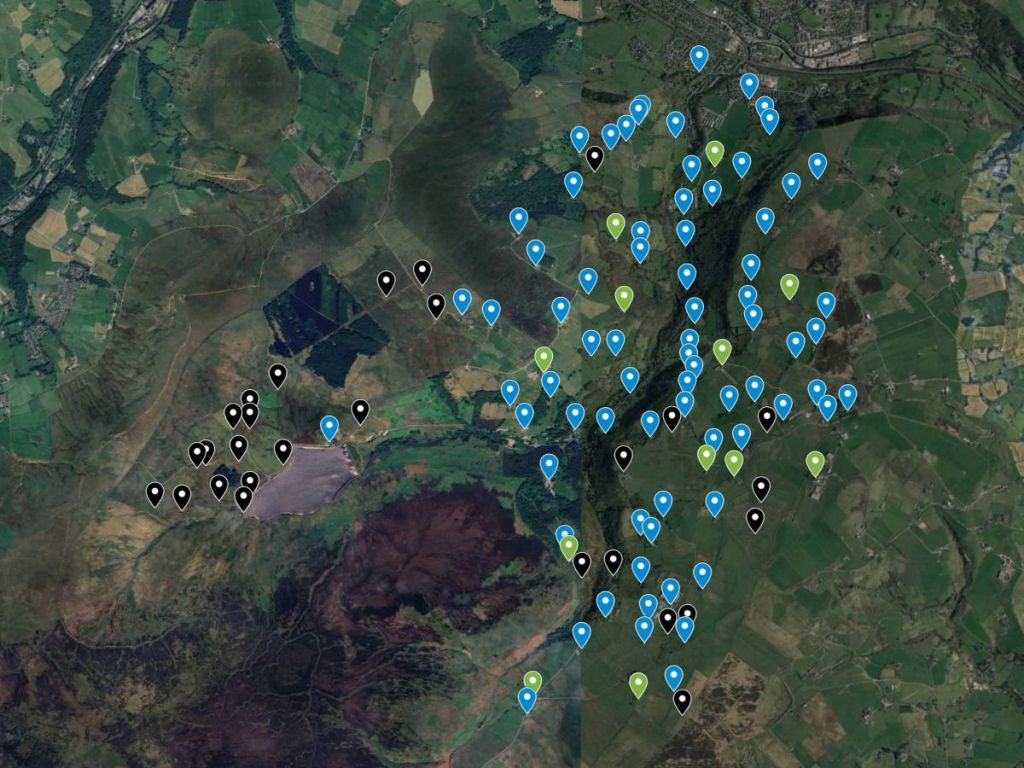

Many others reached these states and worse before being renovated. But the flipside of this success is that they are no longer working farms. So what are the numbers today, 70 years on from Crump? By my reckoning, working farms have declined from 85 in the 1940s (though 22 of these were being farmed from other farms, which I have marked in yellow, so perhaps the 63 in green is a more accurate number)…

…to 13 today, about 10% of the historic number, or 13% of those still working in the 1940s.

I won’t get into exactly how I’m counting as there would no doubt be disagreement on what counts as a working farm as opposed to a smallholding or hobby farm, but these 13 range from Sykes Gate at the head of the valley…

…to Hollin Hey at the bottom…

…and from the big modern barns of Crow Hill…

…to the newer, smaller-scale outfit at Higher House Barn.

And what have been the consequences of the decline from 85 working hill farms in 1943 to just 13 today? First, the area of land under active farming hasn’t shrunk as much as the numbers might suggest. A few of the remaining farms have greatly expanded their holdings – taking on land from neighbouring farms that have become dwellings only – and three farms from just outside the study area now farm land within it. So while farm numbers have collapsed, the overall footprint of land still under agricultural management remains relatively intact.

Second, the number and type of livestock has changed dramatically. One of the most striking things to come out of my research into the history of the upper Calder Valley’s little hill farms is just how recent the dominance of sheep really is. Historically, cattle were by far the mainstay, and only a handful of moorland-edge farms kept sheep. The 1851 census, for instance, records just eight sheep-keeping farms out of 155 in the parish of Wadsworth. A century later, the National Farm Survey showed a similar picture: in the 1940s, as I have detailed, only 11 out of 85 farms in Cragg Vale kept sheep, while 52 were keeping cattle. I don’t know exactly when the big shift occurred, but it seems that sheep numbers peaked in the 1970s and ’80s and were still high in the ’90s, driven by EU headage payments. Since then, flock sizes have generally been in decline.

There’s also been another significant shift that the National Farm Survey doesn’t capture directly: the disappearance of dairy. Many farms once had their own milk rounds or sold their milk through other local routes. Today, dairy farming has virtually vanished from Cragg Vale, and the few remaining cattle are kept chiefly for beef. Pigs and poultry, once commonly kept on small farms, are now very rare.

Third, the look and feel of the landscape has shifted.

With fewer farms working the land, and with many former holdings in private hands no longer managed in traditional ways, the valley has taken on a more patchwork and ‘scruffier’ character compared to that captured in historic photographs. Some land is now used for horses or alpacas; other fields have been planted with trees, or left to revert to woodland – whether by design or through neglect.

When it comes to the architecture of the hill farms, most of the old farmhouses have been rescued and renovated as private dwellings, and their barns, too, have often been converted. So while there are far fewer working farms, there are actually more dwellings than before (though probably a lower population overall compared with the mid-19th century), as former farmsteads have been divided, extended and repurposed for domestic life.

But while the architectural heritage of these little hill farms is, for the most part, safe – rescued, cherished and adapted for modern life – the agricultural heritage they embody survives only tenuously, held together by a few long-rooted farming families and a handful of newer farmers.

I hope that together they can find ways to weave the old and the new into something that can carry the story of the little hill farm forward.

Thank you to David Cant for inviting me to collaborate on the talk; to members of the Cragg Vale History Group for being such excellent hosts; to Karl Grave for allowing me to use his photographs; to Ann Kilbey for supplying me with images from the Pennine Horizons Digital Archive (all uncredited photos are my own); to the members of the Hebden Bridge Local History Society who painstakingly recorded the National Farm Survey returns; and to the Cragg Vale farmers with whom I spoke about their land and its history.

For further reading, see my ‘A History of Farming in the Upper Calder Valley‘.

Love the landscape in the Calder Valley – there’s a real sense of connection to the past especially with the old farmhouses. The essay and photographs are fascinating. Thanks for posting

LikeLike

Very kind, Kath. Thanks for reading.

LikeLike