By Paul Knights (read about my work here).

If you have any comments, please email me at pauljamesknights@gmail.com or post at the bottom of the page.

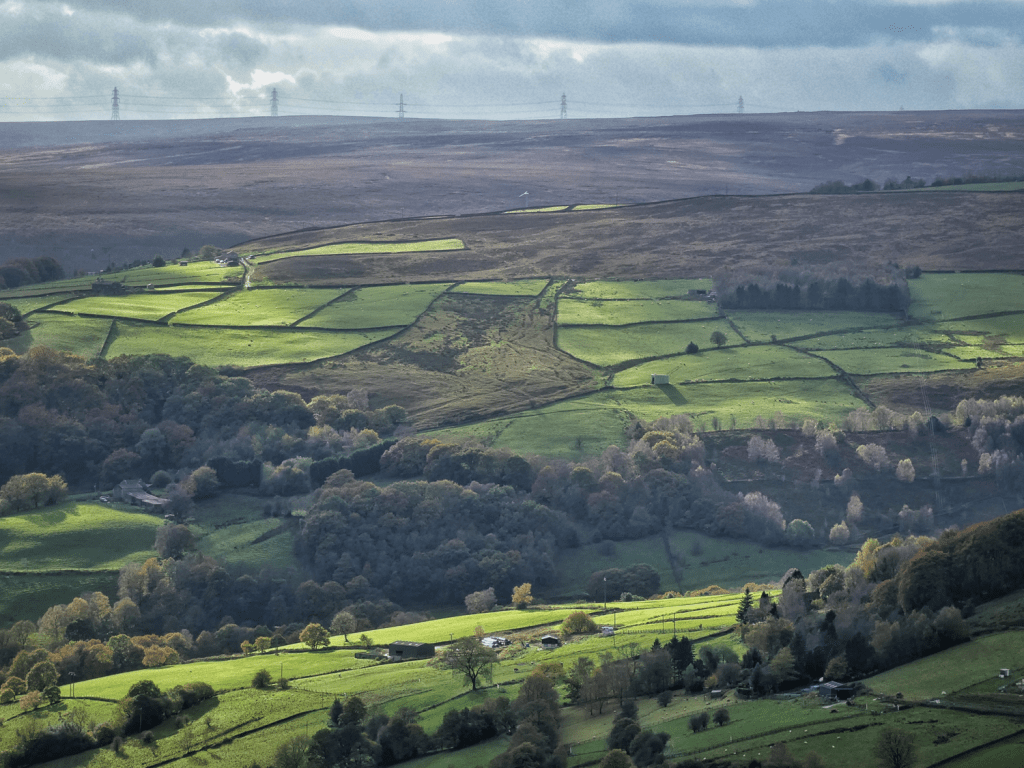

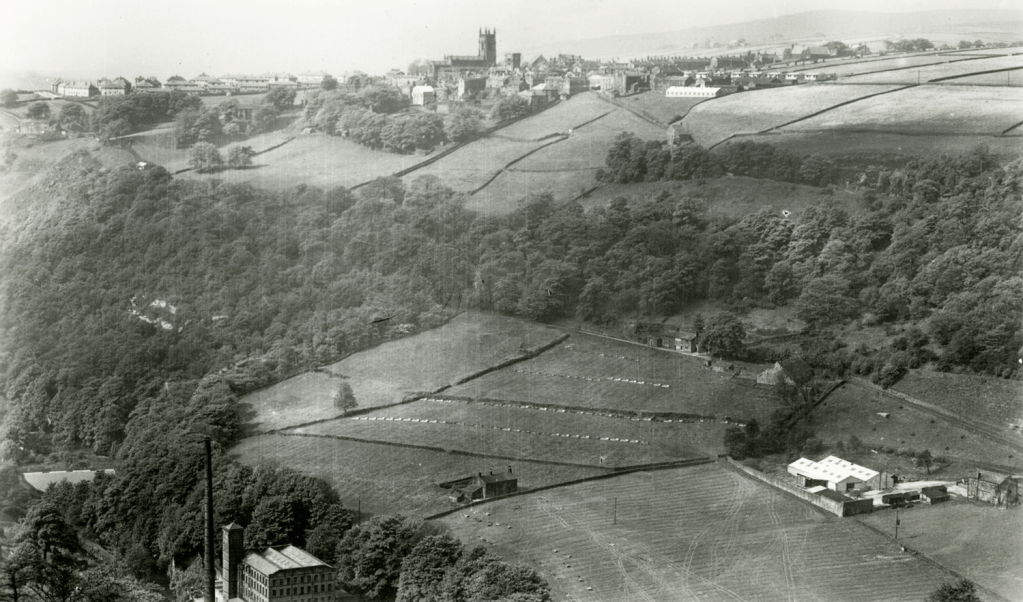

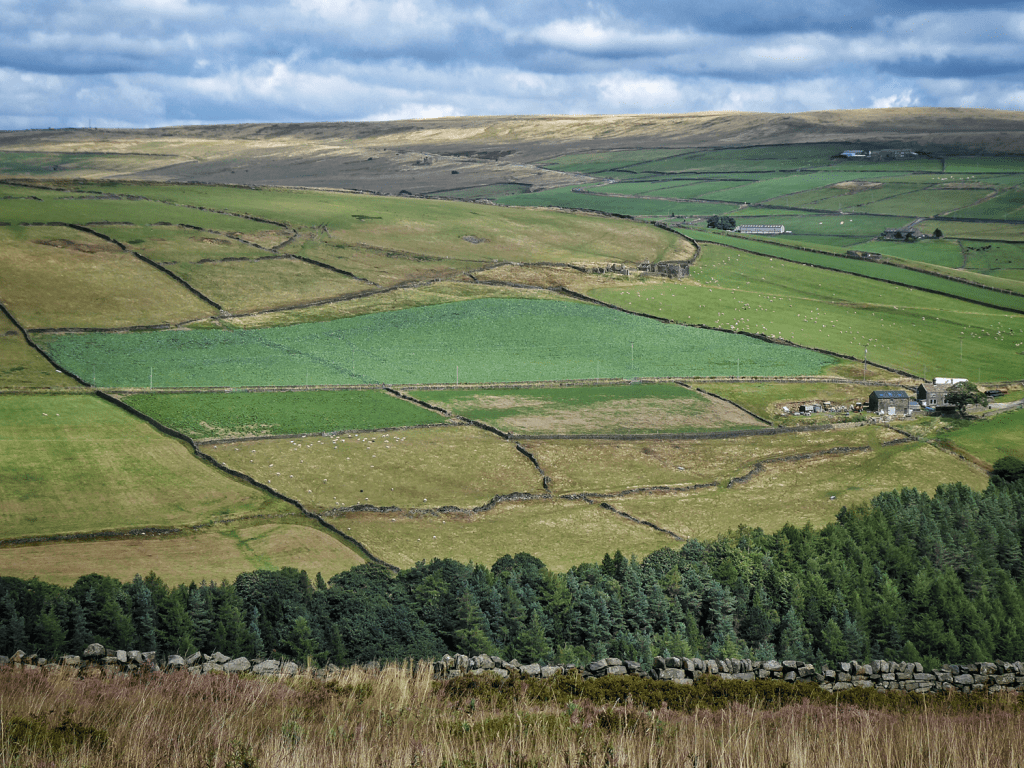

The Upper Calder Valley is a landscape deeply shaped by its farming history. The terrain, climate and soils create a character distinct from the lower valley, and this uniqueness is etched into the pattern of fields and farms we see today.

In this post, I’ll explore these patterns and explain how they came to be, and the story they tell of farming’s development in the upper valley over the centuries. I’ll also delve into what these farms produced during different periods of history.

I’m going to begin by looking at the valley’s farms as they are in the present day. I will focus on the traditional working commercial farms, rather than the valley’s newer, smaller, innovating food producers, because these older operations reflect a direct lineage to the ways farming was practiced in the past. They represent continuity—living evidence of how local agriculture has evolved while still holding onto its roots. These working farms, themselves still small, family-run businesses, can be identified today by their by their tractors, modern barns and stacks of black-wrapped silage bales.

A Tour of the Valley’s Farms

The farms of the Upper Calder Valley make up a rich tapestry of history and tradition, each with its own story to tell. Most of these farms sit on the ‘shelf’ of farmland that lies above the steep inner valley and below the moors.

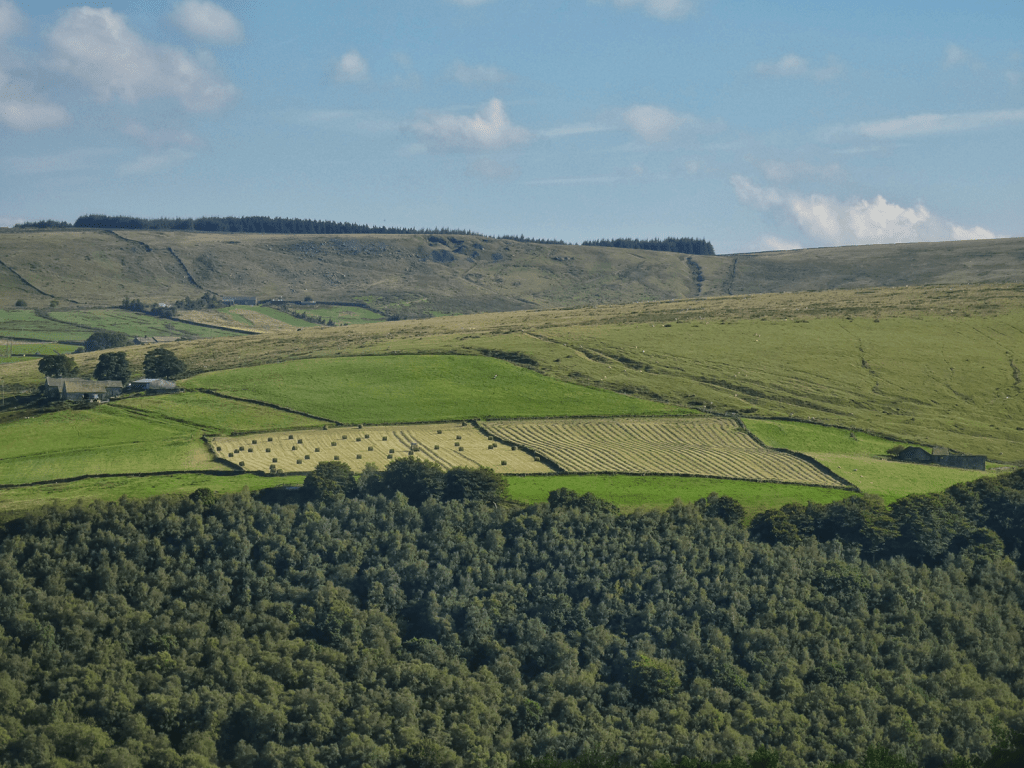

Here’s Old Chamber, perched above Hebden Bridge, on a fine summer’s day after baling…

…and Spinks Hill, enduring the brunt of a winter storm on the shoulder of the moor above Keighley Road.

In Crimsworth Dean, you’ll find Thurrish…

…and White Hole…

…Abel Cote…

…and Laithe.

Above the wooded valley of Hardcastle Crags, a band of farms are strung along the spring line, with Walshaw at one end….

…Mansfield House a little further along…

…and Stony Holt looking down on Midgehole.

All these farms have fascinating histories. Callis Wood, for example, unusually located within the steep inner valley rather than on the shelf above, was a trailblazer in diversification. Back in the 1890s, it hosted enormous picnic parties. Visitors would disembark from trains at Eastwood Station (now vanished) and walk to Callis Wood for its refreshment pavilion. A four-piece band played there every Saturday night through the summer, drawing lively crowds.

That experimentation, searching for ways of making a living in the unforgiving Pennine climate, continues today. Pextenement, for example, has ventured into organic cheese-making, winning many prizes for its produce.

These farms, like Egypt at the head of the Colden Valley…

…and Scammerton, near Blackshaw Head…

…are more than just buildings and fields; they are living connections to the valley’s past, each contributing to the evolving story of farming.

In Erringden, which was once a manorial deer park and opened up for settlement in the 15th century, you can find Horsehold…

…Lower Rough Head…

…and Edge End, its companion sycamores standing sentinel—a common feature of many hill farms in the area.

The Changing Face of Farming

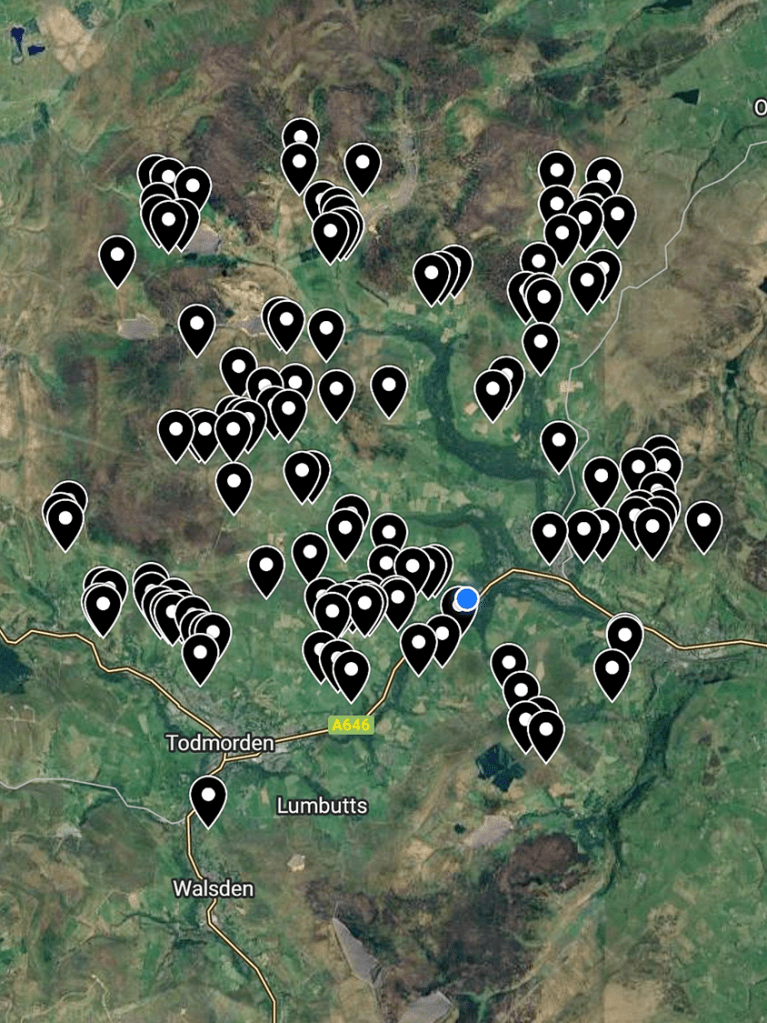

By my reckoning, there are around 50 working commercial farms between Mytholmroyd and Todmorden. (My study area consists of the five ancient townships of Erringden, Langfield, Heptonstall, Wadsworth and Stansfield). Fifty is a fair number, but as you start to look more closely and pay attention to the architecture of local farmhouses, you’ll realize that many of today’s private dwellings dotted across the landscape were once working farms.

There is Bell House, for example, once home to the infamous ‘King’ David Hartley of the Cragg Vale Coiners…

…Rough Top under Stoodley Pike…

…and Middle Nook, near Old Town.

Traditionally, the word ‘farm’ was absent from the names of these properties. It would have been unnecessary, as nearly every dwelling in the area functioned as a farm, and the nature of the place was understood. However, as farming has declined and more of these buildings have been converted into private residences, the word ‘farm’ has often been appended to their names. Estate agents have found this particularly appealing, as the term evokes a romanticised rural lifestyle, even if the property is no longer engaged in food production. This shift reflects both the changing use of the land, and an attempt to preserve, as well as market, the connection to their agricultural past.

These former farms can also sometimes appear to be working, as Marsh (Farm) did on this day, with a tractor rowing up mown grass in its nearby fields. However, while many such former farms are sold with a few acres of fields attached, it is very common for the owners to let the local farmers mow them.

There are over 400 of these former farmhouses in the area, vastly outnumbering the remaining working commercial farms. Most have been converted into multiple dwellings, with not only the houses and cottages occupied, but their barns now housing human rather than bovine residents.

Here is Popples below Blackshaw Head…

…Height in Langfield…

…and Kershaw in Erringden.

Despite no longer occupying the same economic and social role within the landscape as that for which they were originally built, their continued presence connects us to their past and reminds us of the way these places once shaped, and were shaped by, the lives of those who worked the land. At Lady Royd, for instance, we can strain to hear the sounds of its little school, shuttered since 1948, thronged with 40 pupils from the surrounding farms of the Savile Estate…

…while at Rake Head, a former workhouse farm perched on Erringden Moor, we can try to imagine the difficult lives of the 14 paupers who were recorded as living there on the 1871 census.

Cross Ends, tucked beside the Old Haworth Road in Crimsworth Dean, was once used as a chapel…

…and Keb Cote became a pub, the Sportsman’s Arms, one of the highest in England, which itself sadly closed over a decade ago.

The distinctive vernacular architectural heritage of these former farms has, for the most part, been sympathetically preserved or restored thanks to planning regulations. As a result, these buildings stand as tangible reminders of their past.

Kilnshaw, one of the last farms to be built in the area, dates to the 1860s…

…while Hollin Hey was wholesale moved and rebuilt in 1896 from its original 16th-century position to be further down the hillside.

Here is Horrodiddle…

…and Rough Nook beside the lonely road to the Lancashire border.

Hill House is perched on a promontory above Mytholmroyd…

…while Greenland…

…and Popples Close, at the head of the Colden Valley, mark the upper reaches of agricultural settlement.

These properties are scattered reminders of a time when farms truly blanketed the valley tops, forming a dense patchwork of agriculture and rural life.

A Landscape Transformed

Now let’s walk out of the farmyard and into the fields. Mapping the extent of the land farmed paints a remarkable picture. I have drawn around the highest limits of the enclosed fields with a green line. It snakes for 38 miles on the north side of the valley, above the Long Causeway, around the head of the Colden Valley, above Blake Dean, Crimsworth Dean, and Old Town, and then for another 10 miles on the south side of the Calder, around Withens Clough, and under Stoodley Pike and Gaddings Dam. There are also three ‘islands’ of enclosures in the north-west of the area: Widdop, Gorple and Raistrick Greave.

The total area encompassed by these lines is approximately 15,000 acres. However, we need to account for several deductions from this total. Areas of unenclosed moorland within the green lines—Erringden Moor, Staups Moor, Lord Piece, the Bride Stones and other smaller patches that escaped the process of enclosure and improvement—are marked out in blue.

Also, the urban-industrialised strip along the valley floor and the woodlands on the steep, inner valley sides and tributary cloughs must be deducted from the total.

These slopes and cloughs have always been predominantly wooded. Even in the 19th century, at the minimum extent of woodland coverage, there were still 62 named woods on the valley sides, but they were fragmented, with fields created on the more gentle, less boulder-strewn slopes separating them from one another. But after the Second World War, when farms needed a tractor to remain commercially viable, these inclines, inaccessible to machinery, were abandoned, and over the last 70–80 years have quietly reforested themselves, joining the individual woods to one another in a contiguous band of woodland that now covers about 1,500 acres (2.3 square miles, marked in blue on the map below). If you were to start from Todmorden, and walk up into all the individual cloughs and tributaries on the north side of the Calder to Mytholmroyd and back to your start point doing the same on the south side, you could walk for 22 miles without ever breaking from the shade of the woodland canopy.

After we have made these three kinds of deductions, we are left with around 12,000 acres of enclosed land. At its peak in the mid-19th century, this area supported about 575 farms—a much greater density to the considerably sparser settlement of places like the Yorkshire Dales or the Peak District.

Sharing out those 12,000 acres between 575 farms gives an average of just 21 acres per farm. This has been a rough and ready way of working out the average, but it aligns well with historical records.

Why So Many Farms?

The extraordinary density of farms in the Upper Calder Valley can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, from medieval times through the 1600s, the climate worsened, becoming colder and more challenging for farming. Secondly, through this period the population increased, driving demand for farmland. And thirdly, the area followed multiple inheritance traditions, according to which, unlike primogeniture, where the eldest son inherits everything, property was divided equally among all sons. This practice led to the continual subdivision of farms, reducing their average size over generations.

These three factors made deriving a livelihood from farming alone incredibly challenging, meaning hill farmers were forced to look for a secondary source of income. It was found in handloom weaving. Almost every farm had at least one loom. This provided families with an additional income stream and allowed them to continue farming on a subsistence basis.

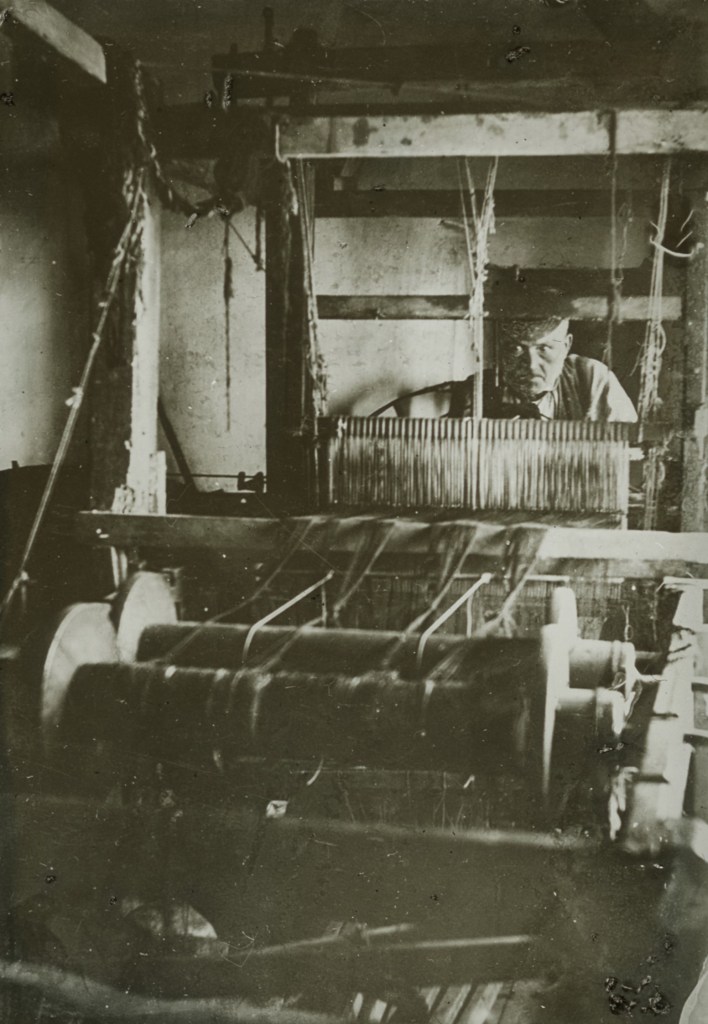

We can catch a glimpse of this dual livelihood that sustained local farming families for centuries in just a few surviving photographs. Here is Jack o’t’ Bog Eggs (Bog Eggs, above Old Town, is now called Allswell Farm). He was the last handloom weaver in the parish of Wadsworth, still at his work in 1896.

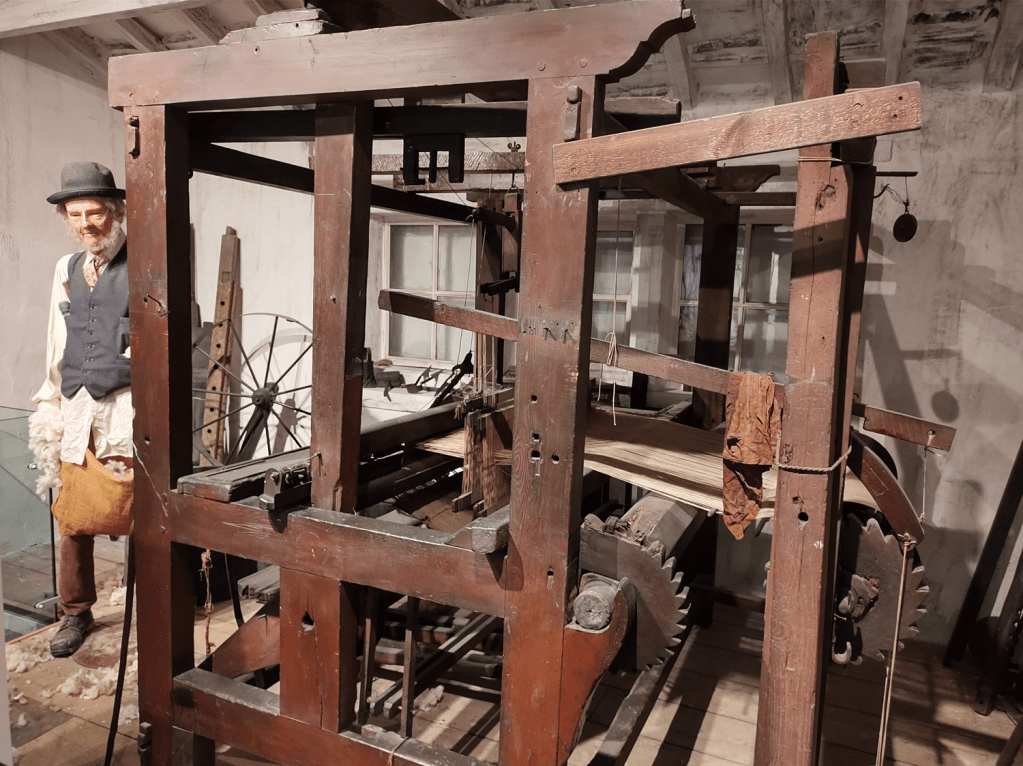

A replica loom built for The Gallows Pole TV show is on display at Heptonstall Museum…

…but a real example can be found at Cliffe Castle Museum in Keighley. It belonged to Timmy Feather, the last handloom weaver in Haworth.

The Evolution of Enclosures

The history of farming in the valley is also written in the changing pattern and shapes of its fields, which were called enclosures. Early enclosures, dating from the 12th to the 16th centuries, were informal and resulted in irregular, higgledy-piggledy patterns, as seen on the south-facing slopes of Stansfield, for example.

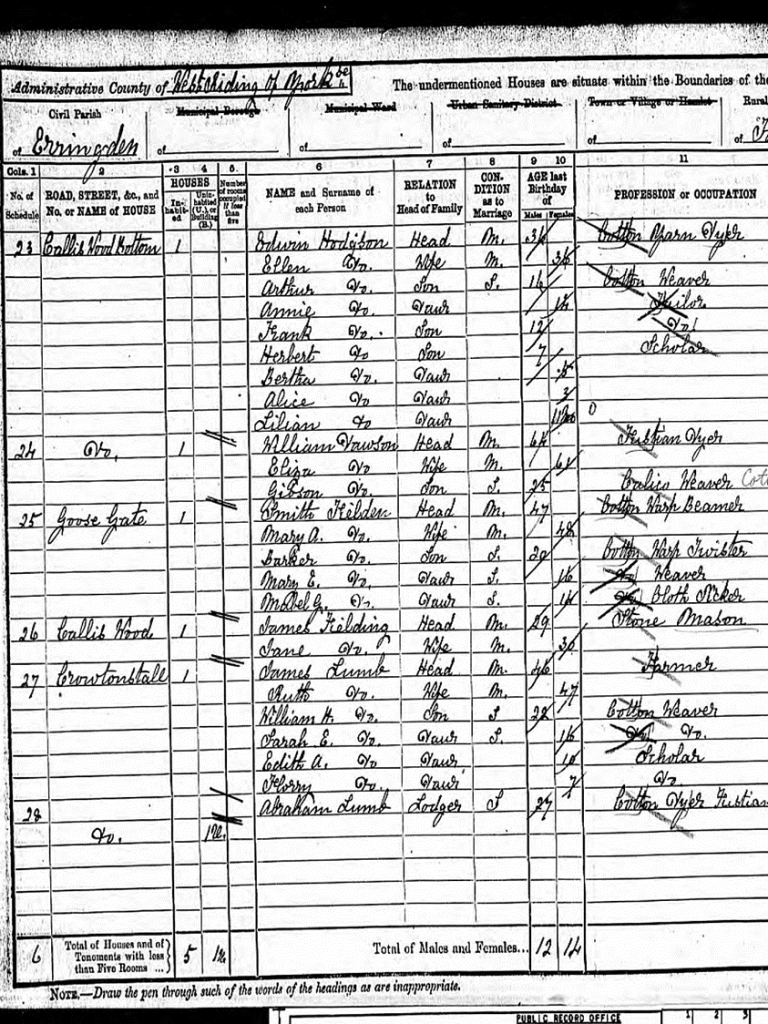

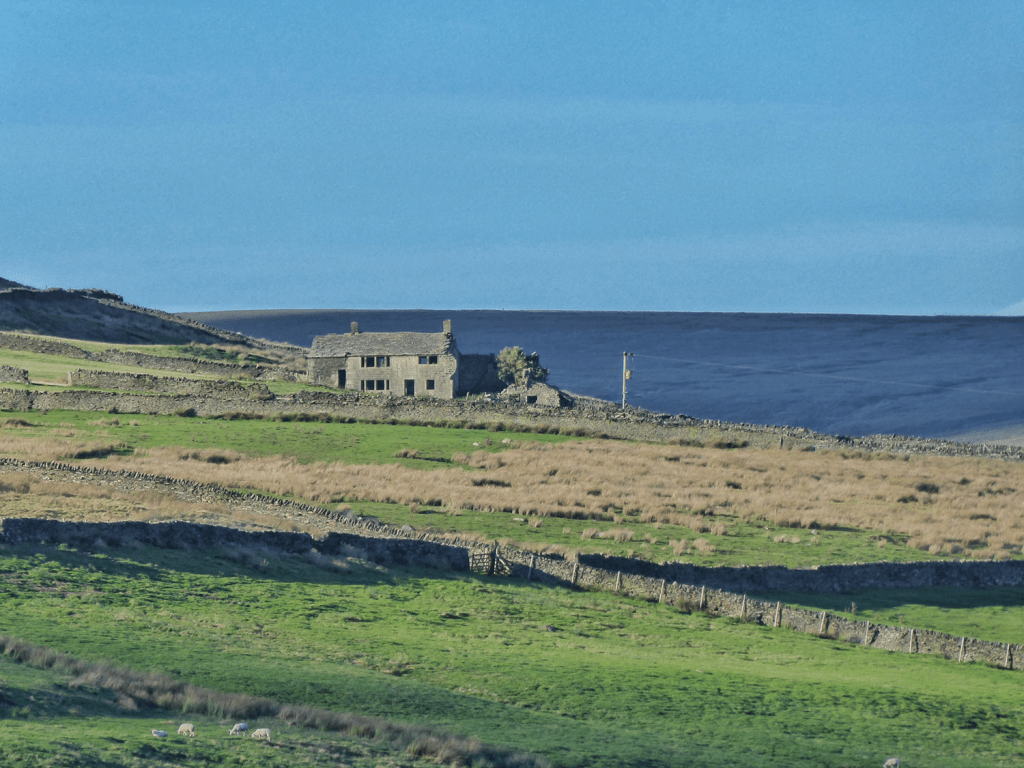

There are other fields likely to be ancient, like those around Cruttonstall, a 17th-century farmhouse on the site of a settlement mentioned in the Domesday Book. Cruttonstall was once a vaccary, a medieval manorial cattle-breeding farm. It later ended up within the Erringden Deer Park in the 14th and 15th centuries.

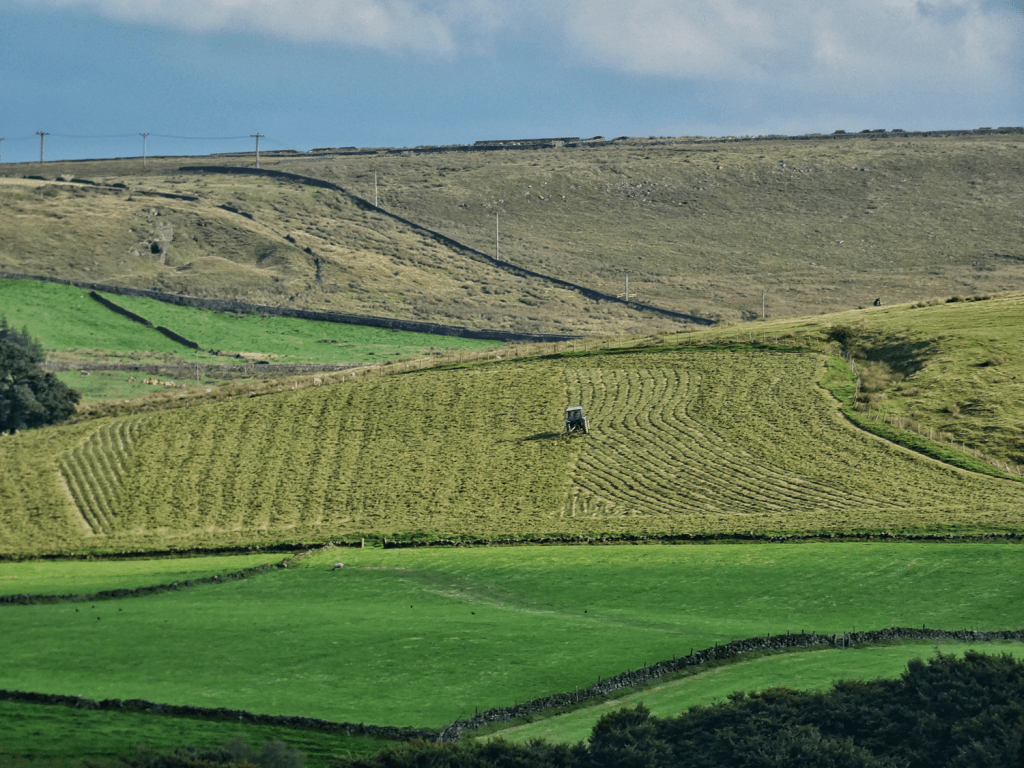

As the local population grew, the process of enclosure continued into the 19th century, becoming more formalized. The irregular shapes gave way to straighter, more ordered fields. Some of these were created by rearranging and reordering already improved land, such as those at Erringden Grange in the 1820s and ’30s…

…or these above the three Horsewood farms crouched under Langfield Edge, whose ragged walls were straightened and extended as part of the Fielden family’s scheme to keep their mill workers employed during the Amercian Civil War-induced ‘Cotton Famine’ of the 1860s.

However, most enclosures of this period were made anew by ‘taking in’ land from the moorland, or ‘waste’, as it was called. These new fields were called ‘intakes’. Here are some on the slopes of Staups Moor, created out of a parliamentary act of 1816…

…while the neat grid of 40 or so enclosures created out of Erringden Moor (the highest green fields in the image below) were a project of the Rawson family, completed to great fanfare in 1836.

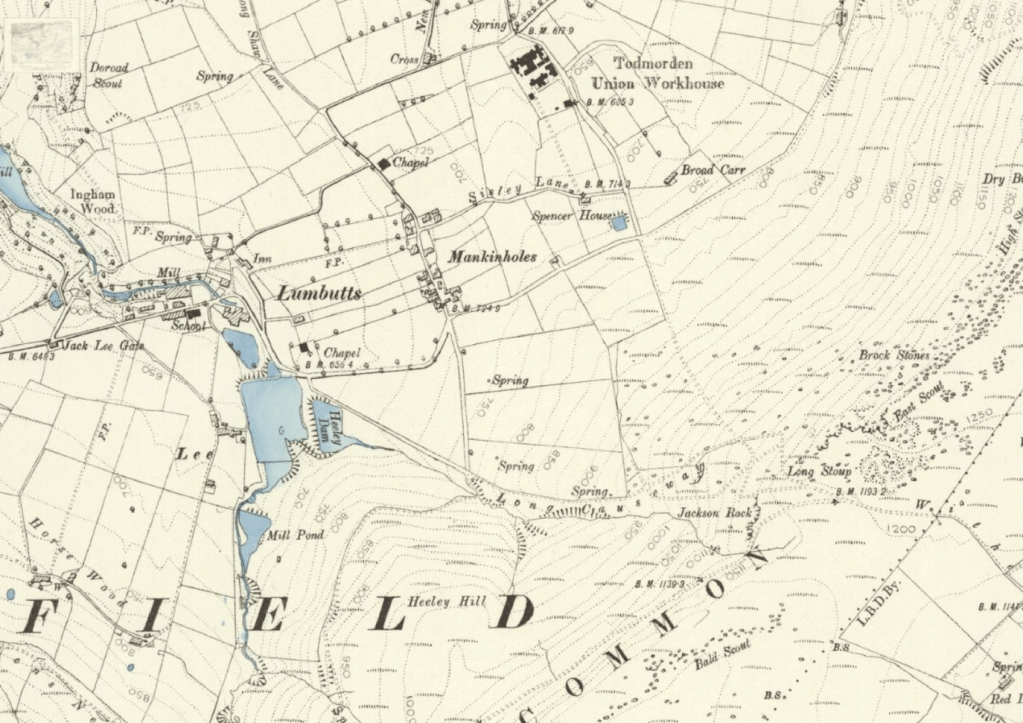

The process was ongoing well into the second half of the 19th century. For example, in the centre of this extract from the 1848-surveyed map of Mankinholes, we can see that there is open moorland stretching down to the village from the Long Causeway…

…but by the 1894 edition, four new fields have appeared…

…which can be seen here.

Fields were pushed as high as possible, reaching the limits of cultivation. The very highest enclosure wall, snaking over Jack Stones on Stansfield Moor, stands at 1,456 feet.

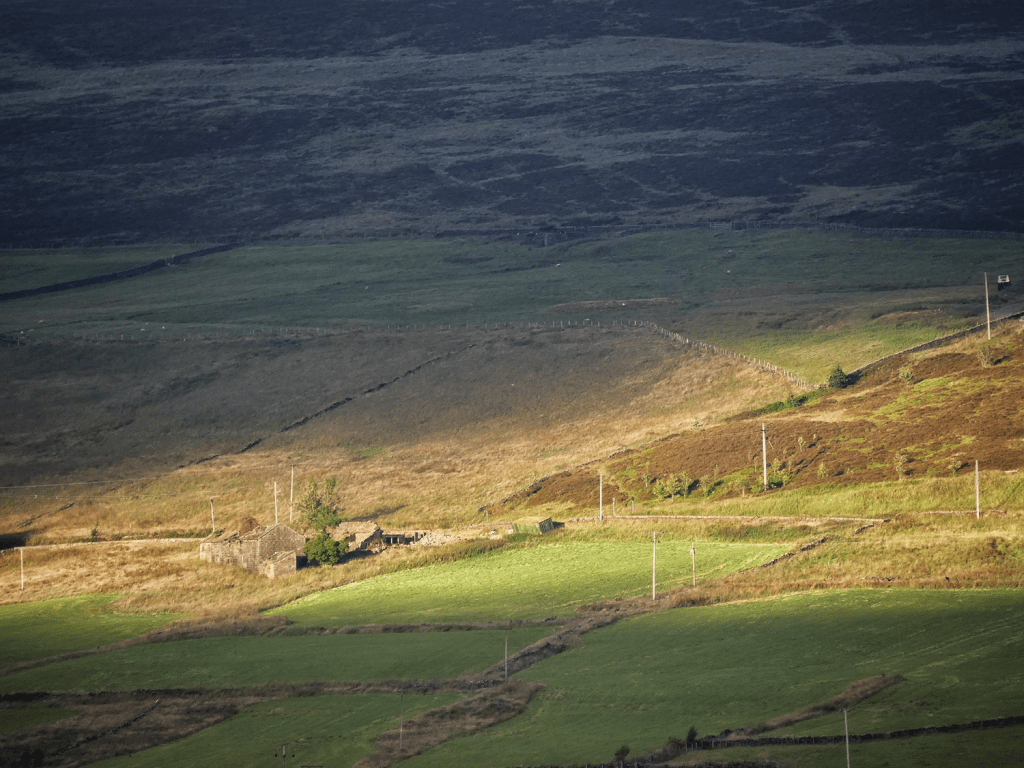

The difference between the enclosed fields and the moorland is stark. On certain days, in specific lighting conditions, you can clearly see where improved green pastures meets the rough brown vegetation of the moors, such as here at Bell House Moor…

…or here above Edge Lane in the Colden Valley, where the enclosures surrounding the stubby ruins of Wham and those on Hot Stones Hill bite up into Heptonstall Moor.

At other times, it is specific snow conditions that reveal the contrast. Here, a light dusting has settled on the unique, free-floating enclosure surrounding Old Hold, but the moorland that surrounds it remains its normal sombre winter colour.

How Fields Were Created

Carving these fields out of the moor required unimaginable labour. Rocks and the roots of tough moorland vegetation were painstakingly excavated using the locally distinctive graving spade, a wrought-iron-bladed tool used by one labourer, who would slice into the turf and push it forward, while a second, using a tool called a hack, would turn the turf over.

And this is to say nothing of the construction of the untold thousands of miles of dry stone walls which actually enclosed the land…

…or the effort that went into drainage; stone or pot field drains crisscross the landscape under the surface, and were vital in making these fields viable for farming. Mostly invisible, sometimes their subterranean patterns reveal themselves.

The cleared land was initially used for crops like oats or potatoes, which could be grown for a few years before the soil was exhausted. Afterward, the land was turned into permanent grassland.

This entire landscape—the fields, walls and drains—was created through immense effort, leaving us with the remarkable legacy of labour that defines the Upper Calder Valley today.

The Decline of Hill Farms: From Abandonment to Renewal

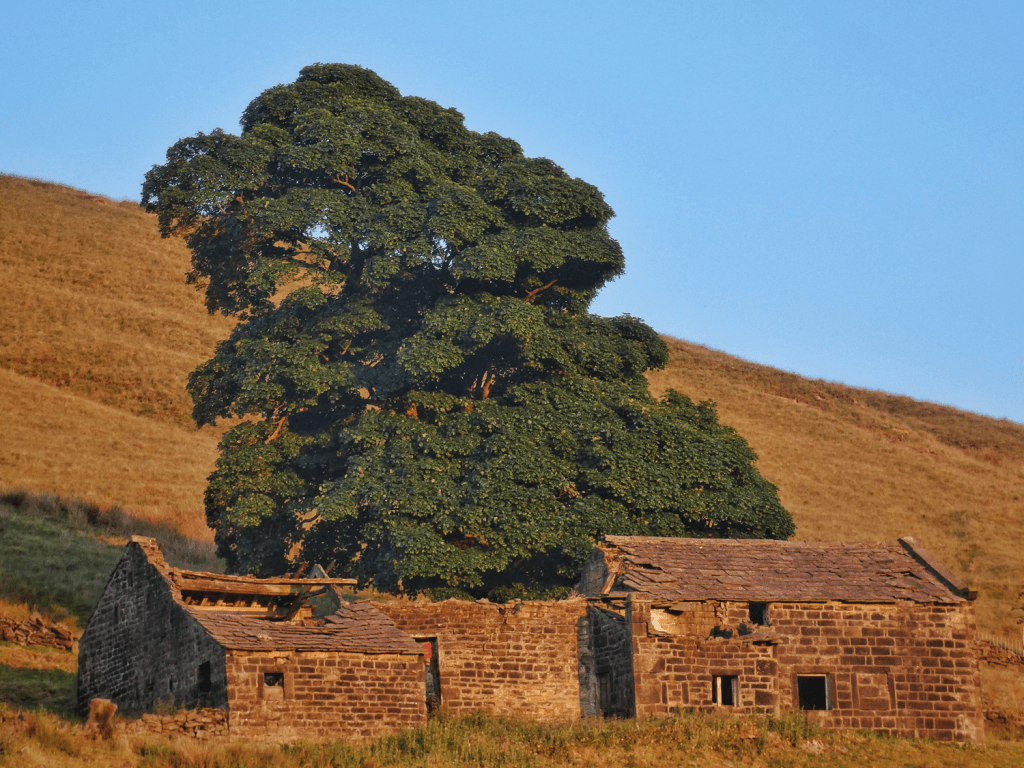

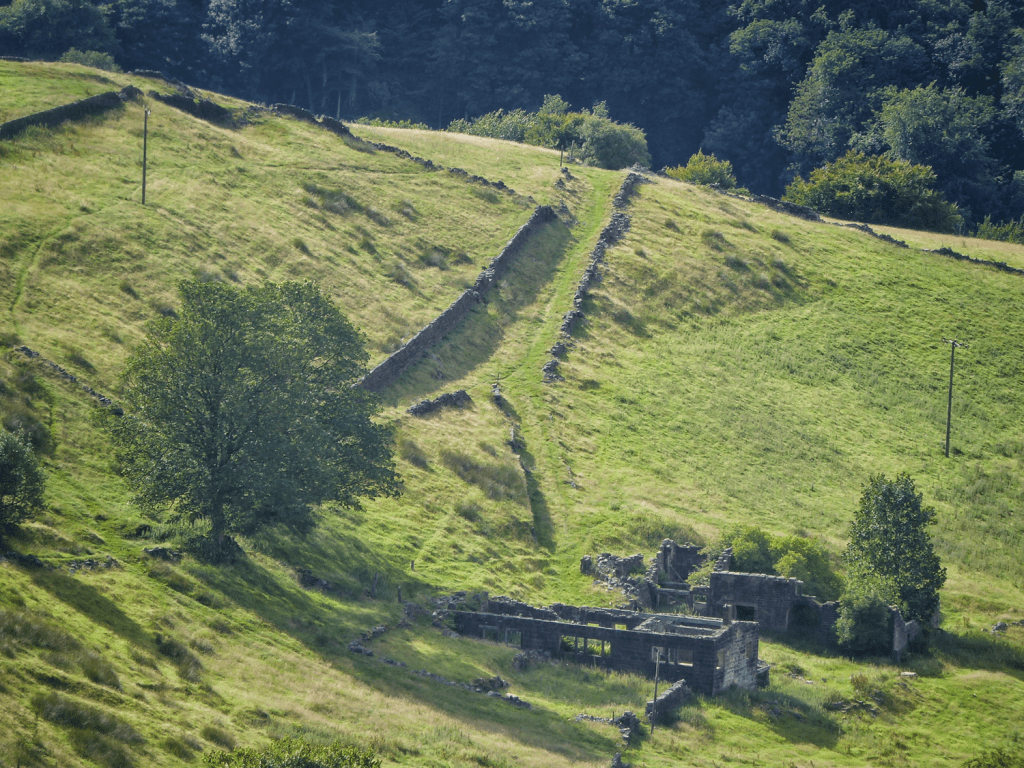

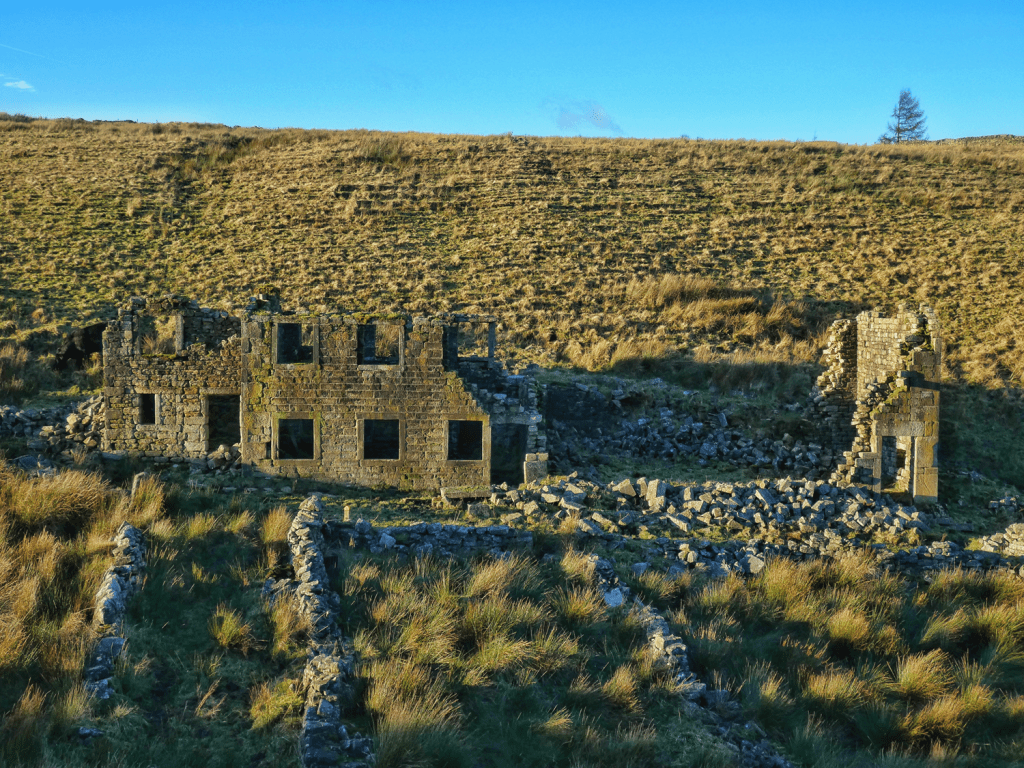

The process of taking in new fields from the moors and building new farms continued into the second half of the 19th century. However, as we look around the landscape today, we find many derelict and ruined farmhouses. Here, for example, is Handibut Hill in Crimsworth Dean…

…with Roms Greave at the head of the valley…

…and Clough Head above Hardcastle Crags.

There are approximately 100 of these abandoned farmhouses in the Upper Calder Valley. Of these, 40 or so still have substantial remains standing, another 30 or so are reduced to a footprint of foundations, scattered stones, or rotting roof beams, and the remaining 20 or so have left barely a trace that they were ever there at all.

What Caused the Abandonment?

The decline of these farms was driven by significant economic and social changes, starting with the collapse of the dual economy that had created and sustained the density of hill farms. Farmers relied on both subsistence farming and income from handloom weaving. But with the rise of water-powered mills in the cloughs and then steam-powered mills in the valley bottom, this system was swept away.

Even as the last farms were being built in the 1860s, the abandonment was beginning. For example, the sycamore marking the site of Mare Greave grows on the site of a farm that was empty by 1861.

Raistrick Greave was abandoned by the 1880s…

…as was Thorps.

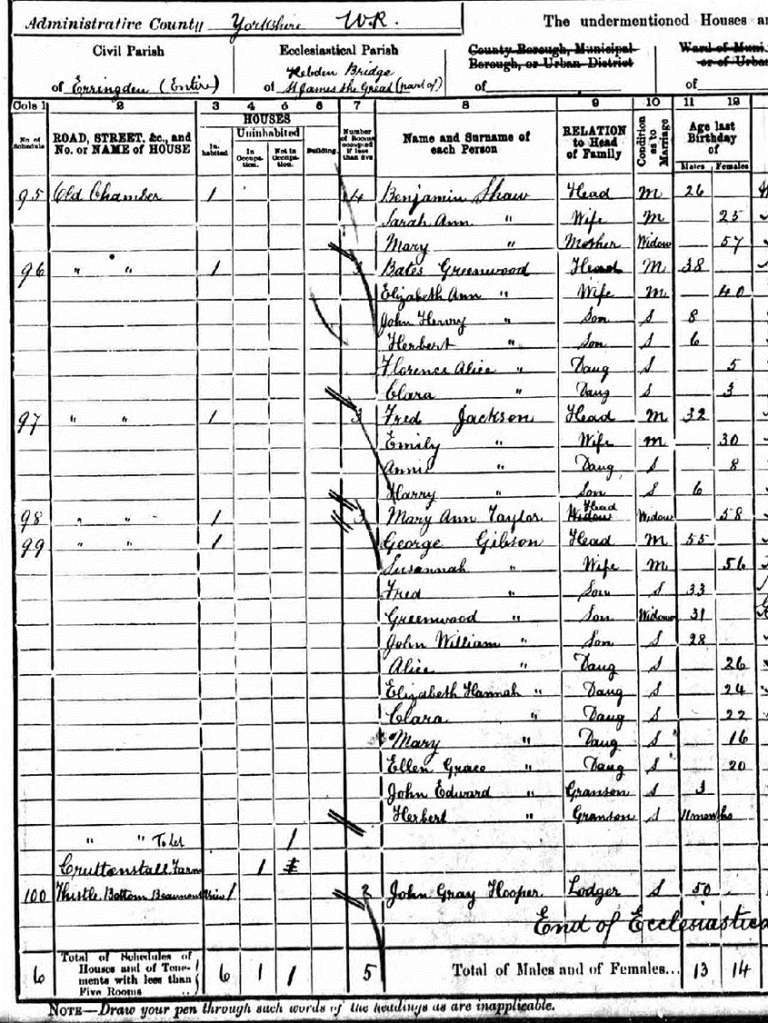

At Cruttonstall, the 1891 census records James Lumb and his family living there…

…but by 1901 it was empty…

…and by 1911 it had fallen into disuse. Today, it has stood empty for more than 120 years.

The Role of Reservoirs

Reservoirs bore responsibility for whole areas being depopulated. Although they did not flood any farmhouses directly, they drowned some of the fields of many, plus there was a prohibition on keeping cattle on their catchments, meaning that although farmers were not evicted, deriving any livelihood from farming was impossible.

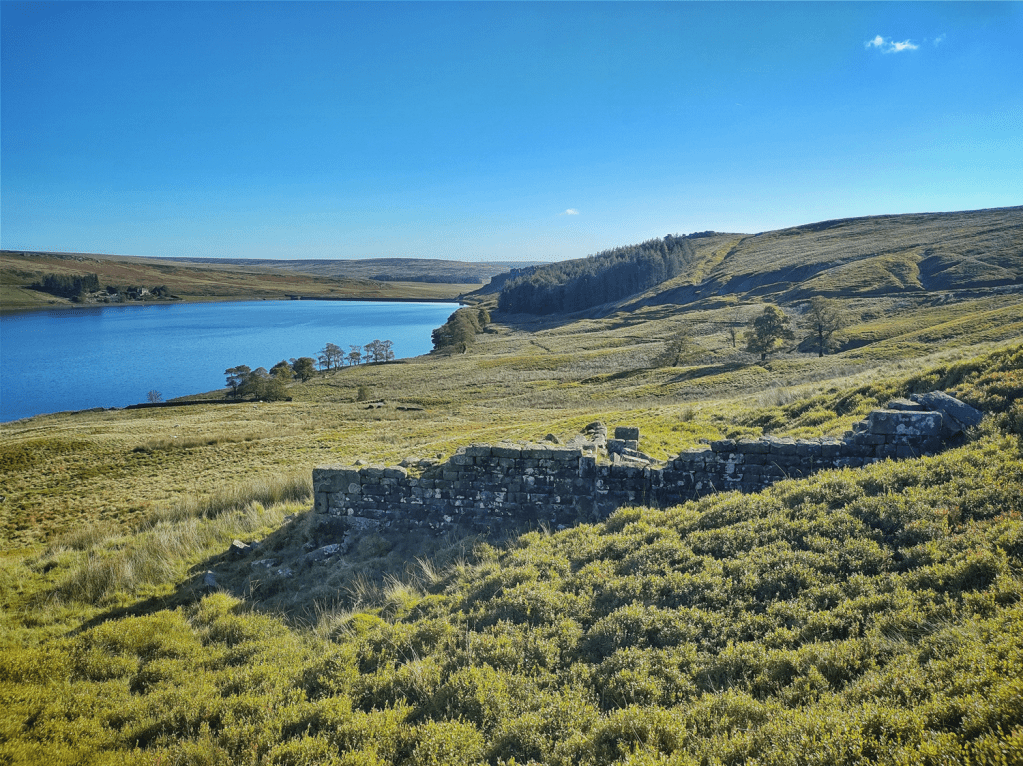

The first of these, Widdop Reservoir, completed in 1871 for the Halifax Corporation, caused the loss of a community of eight farms. Of the four on the north shore, only Lower Houses and the barn of Higher Houses remain…

…while on the south side, the ruins of World’s End and Wood Plumpton are just about traceable, but Ladies Walk and Old House have entirely vanished.

The community of seven farms at Alcomden, as the lower reaches of Walshaw Dean were known, also did not long survive the coming of the three reservoirs in the early 1900s.

And lonely Gorple, marooned on its island of enclosures among the vast moors, while still inhabited by the time of the 1911 census, cannot have remained so for long after the navvies arrived to construct the two Gorple reservoirs in the 1920s.

Marginal Land and Farm Abandonment

Many farms on the higher, more marginal land couldn’t survive in the shifting economy. Law Hill, built by the Rawson family in 1836, was abandoned after just 30 years.

There is some evidence of empty farms sometimes being reoccupied for a time. Pad Laithe appears to have been abandoned for decades after the 1890s, but I have recently come across a photograph of it apparently occupied again in 1938.

Nook was likely abandoned by the 1930s…

…while above it, even though it survived long enough to be connected to the electricity network, Coppy has been empty since the mid-1950s.

Red Dikes outlasted almost all of the community of 15 farms that once occupied Withens Clough. In 1893, when the Morley Corporation built its reservoir there, all but Red Dikes and Pasture (still inhabited today) were cleared away, and very little trace of them remains. But Tommy Ormerod, the last in a long line of gamekeepers living at Red Dikes, could not face another winter like that of 1947, and crossed the moor for kinder climes.

Not all of today’s derelict farmhouses were on marginal land, though. Burnt Acres is snug in Parrock Clough, but in a terrible case of nominative determinism, succumbed to a fire in the 1960s.

East Rodwell End also had a fine position, low down on the farmland shelf above Todmorden, but has been empty since the late-1970s. Today, it is up for sale for £695,000—an indication of how the landscape continues to evolve.

And all that remains of Beverley End, sheltered in Jumble Hole Clough, are its remarkable tenter terraces—used for stretching out drying woollen cloth on wooden tenter frames—and their silent bee boles.

Archiving the Changing Fortunes of Farmhouses

The process of farm abandonment, as we have seen, continued for a little over a century from the 1860s. While many were permanently abandoned, others were rescued and renovated, particularly from the 1960s. The trajectory of this process has been captured in several remarkable photographic archives.

Karl Grave’s project for the Hebden Bridge Camera Club in the late-1970s helps us determine which farms that were ruinous then, such as Colden Water…

…are even more ruinous today…

…but also which farms that were abandoned then, such as Haven…

…came to be restored and reinhabited.

Similarly, Roger Birch’s collection of farmer portraits, which can be seen at the Top Brink pub or in his book Todmorden People: A Celebration of Local Folk 1973–1996, and the architectural historian Christopher Stell’s photographs of local farmhouses from the late-1950s contained in his Masters thesis, are invaluable records of the state of Calder Valley farms at times of great change. Unfortunately, I cannot show images from either collection here.

Happily, though, we also have the astonishing archive of Ralph Cross, recently preserved in the Pennine Horizons Digital Archive. Working in the 1960s and ’70s, he recorded the architecture of farms and barns, including renovations like Old Edge, photographed in 1963…

…and again in 1974 as restoration began.

This process of renewal is still ongoing: Far Nook, empty since the 1970s when Ernest Stansfield left, is now being restored.

Despite the presence of about 100 ruins, the real story is how few farmhouses were truly lost. Over 400 have transitioned from working farms to preserved and renovated homes. This remarkable preservation speaks to the resilience of the Calder Valley’s architecture and its enduring connection to the past.

The Fate of the Fields

With less than 10% of the valley’s farms still working, one might expect a significant loss of the farmland itself. Surprisingly, this isn’t the case. While some fields have been reclaimed by the moor, the vast majority remain cultivated.

Some examples of fields that have returned to the ‘waste’ include those of Wood Plumpton, overtaken by bilberry and rough moorland grasses…

…and those that once surrounded Lower Good Greave, its absence marked by the two sycamores, and Upper Good Greave, the low ruins of which you can see in the strip of sun beyond.

The pastures and meadows of Pad Laithe, Noah Dale and Broad Holme in the upper reaches of the Colden Valley, while still grazed by hardy Aberdeen Angus cattle, are not what they must once have been…

…while at the head of Withens Clough, where the farms of Rough and Watergate are marked by memorial sycamores, traces of green among the rushes betray their past use as more productive grazing, but these are fading as the decades pass.

The 15 acres of enclosures once cultivated at Raistrick Greave are now virtually indistinguishable from the surrounding moorland…

…and while at 1,300 feet, Gorple‘s seven fields were unlikely ever to have been lushly productive, today, after patiently lapping at the green shores for centuries, the moorland sea has finally submerged the island our ancestors once raised here.

The Farming Cycle

But just as with the farm buildings themselves, the proper perspective to take is not how much, but how little has been lost. Of the 12,000 acres of enclosed land, most have been retained as productive pasture (permanent grazing) and meadow (from which stock is excluded in spring to allow the grass to grow, which is then mown in summer to preserve for winter fodder). This is because the relatively few remaining working farms have expanded their holdings, taking on land once farmed by the hundreds of abandoned and former farmhouses. Even in areas that have reverted somewhat to the ‘waste’ from which they were once claimed, much is still used for rough grazing.

The farming calendar that maintains these fields has changed remarkably little over the centuries. Today’s farmers follow practices that would be familiar to their predecessors. The land is grazed…

…the stock gathered…

…and moved between different fields.

Perhaps some supplementary feed is put out.

In addition to the traditional practice of spreading lime (pulverised limestone) to reduce the acidity of the soil and thereby improve productivity…

…modern machinery and chemicals offer some additional options for stimulating grass growth: fields might be flat-rolled…

…or a dressing of nitrogen fertiliser applied.

In summer, the meadows are mown…

…and the cut grass is then turned, or ‘tedded’, to help it dry…

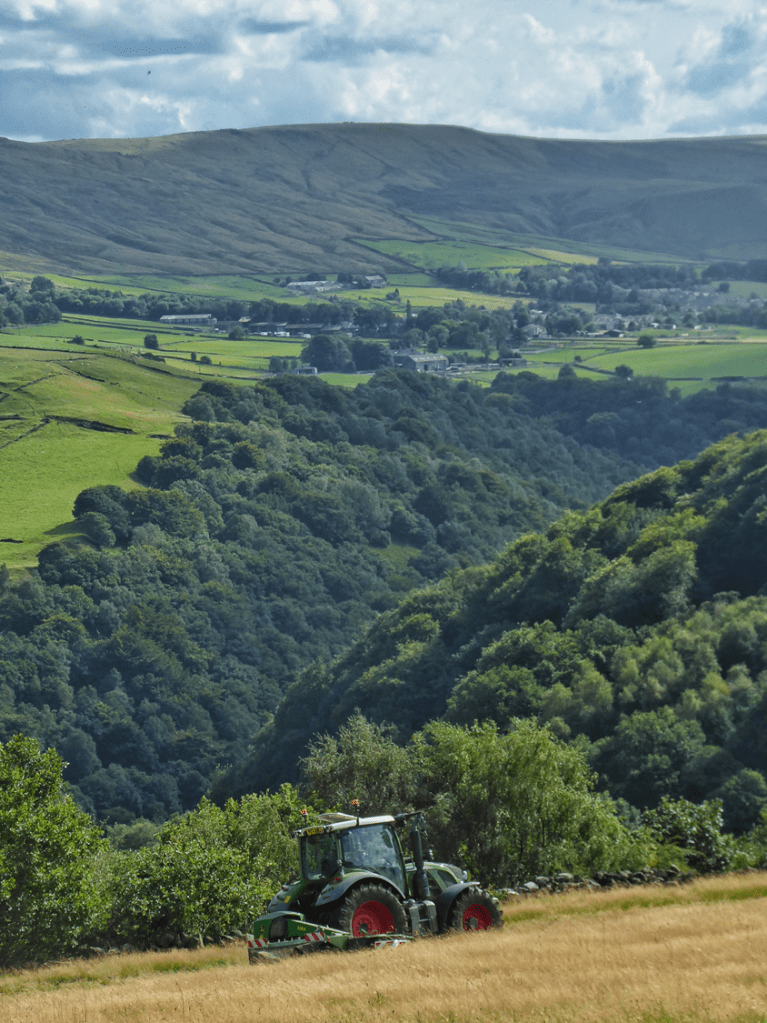

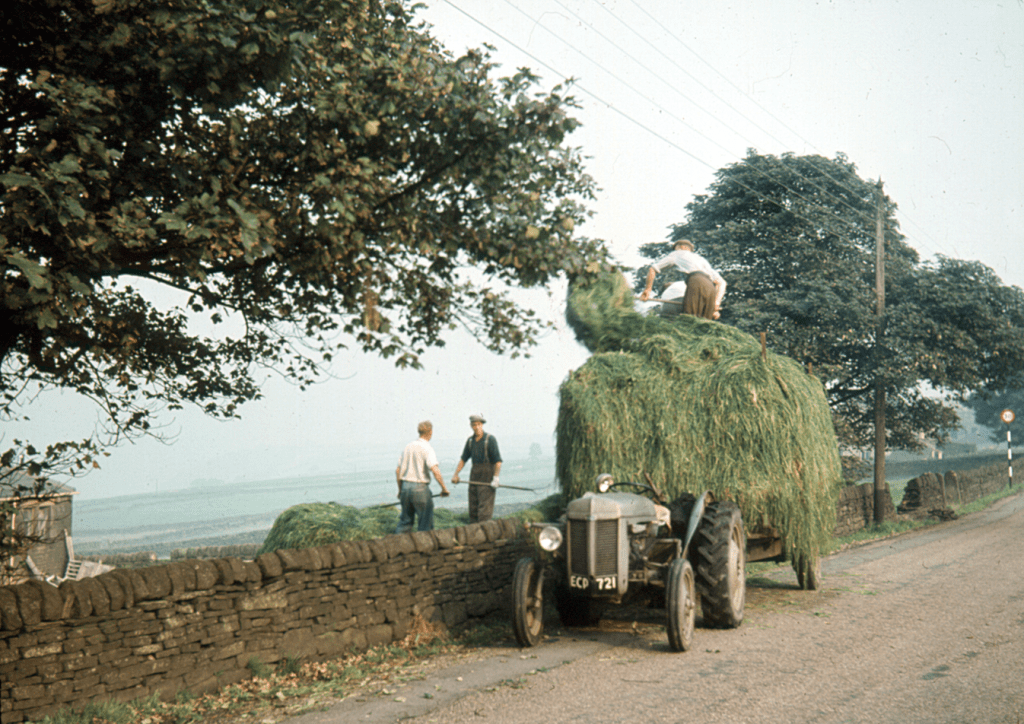

…then rowed up…

…ready for baling, either as big silage or haylage bales, which are wrapped in black plastic…

…or more traditional small hay bales.

Dressings of muck are applied to replace lost nutrients in the soil.

Cattle are brought into the barn…

…and fed with the grass preserved from the meadows through the winter…

…or else, with the hardier breeds, stay out all winter…

…with the help of some bales being brought out to them in the lean months.

Sheep stay out all winter, also with the help of some supplementary feeding…

…which is where small bales can come in handy, fitting on a quad bike so the use of tractors on wet fields can be avoided.

The tups having been put to the ewes traditionally in November, mid-April is the typical start of lambing.

This cycle ensures that the fields remain productive, perpetuating a tradition that has created and maintained the Calder Valley landscape for centuries.

What Did These Farms Produce?

Our understanding of historic farm production comes from a variety of sources (all of which are listed in the bibliography):

- Probate records: Wills and inventories from the 1600s and 1700s frequently mention stock and farming implements.

- Manorial court rolls: Settling disputes involving livestock and tools, these offer glimpses into historic farming practices.

- Agricultural statistics: Systematic records from 1866, with earlier snapshots during the Napoleonic Wars, detail crops and livestock.

- First-hand accounts: Five detailed accounts from 20th-century farmers provide invaluable insights.

- Secondary sources: These draw on the above materials to create a broader picture.

While the evidence is patchy, it provides enough detail to form a reliable understanding of what these farms produced and how.

Cattle: A Farming Staple

Cattle have always been at the heart of farming here. The valley’s medieval vaccaries—cattle-breeding farms—set the stage for centuries of reliance on livestock. Probate records from the 1600s and 1700s consistently mention cattle, as do agricultural statistics, which show increases in cattle numbers during the 19th century.

The architecture of farms reflects this focus: barns (locally called laithes) were designed to house cattle. The lower floor, or mistal (sometimes called a shippon), held the cattle in their stalls (booses, or boices), while the upper floor stored hay in the haymow.

By the 19th century, dairy shorthorns became the breed of choice, valued for their milk and their ability to be fattened for slaughter at the end of their lives.

Initially, cattle were kept solely for subsistence, with farming families consuming salt beef through the winter. For a long time, meat would have been unaffordable for many landless millworkers. However, as populations and incomes grew, farmers began raising additional cattle to meet demand. Herds were driven from the Craven grasslands in the southern Yorkshire Dales to markets at Hebden Bridge, Todmorden and Keb Cote (the former Sportsman’s Arms).

Cows were milked during the era of subsistence farming, but from the 1780s onward, as industrialisation spurred the growth of a landless millworking population, farmers identified a new market opportunity. This shift became increasingly significant as the handloom weaving economy declined. Agricultural records from this period reveal a rise in the number of milk cows relative to other cattle.

Initially, people would have collected milk directly from farms, but over time, networks of retail distribution developed. Farmers began carrying milk churns on their backs or using donkey packsaddles, eventually transitioning to one-horse traps to expand their delivery reach. Milk rounds became a common feature of many farms.

Like much of the country, the number of dairy farms in the area has drastically declined. Today, there are only two remaining dairy farms in the region of focus, and neither operates a milk round. However, just outside the area, two dairy farms continue this tradition. John Hitchen, at Old Crib above Luddenden Foot, maintains a milk round serving Hebden Bridge.

Here’s a photo of my son watching the Old Crib herd as they more or less guided themselves to the parlour for afternoon milking.

Another local dairy, operated by the Midgley family at Dean Head in Luddenden, also serves the valley with a milk round. Here’s their herd, patiently awaiting their turn in the small milking parlour.

Butter, too, was important. In 1913, Mrs. Greenwood at Outwood in Crimsworth Dean was producing up to 30 pounds of butter weekly, selling it in Mytholmroyd for 1s 4d per pound.

There is little mention of cheese in the historical records, but it can be assumed that small cheeses were made for domestic consumption, as would have been typical on most farms. However, cheese-making never seems to have been a significant enterprise in this area. Given that history, it’s a fortunate development that the Pextenement Cheese Company now operates here, bringing local cheese production into the modern era.

Sheep: A Surprising History

Sheep are, of course, a ubiquitous sight in the landscape today, but this is a relatively recent development. The 17th- and 18th-century probate records reveal that only a minority of farmers kept sheep. Numbers likely increased when local breeds—the Lonk, the Whitefaced Woodland and the Derbyshire Gritstone—were improved to better tolerate the wet and acidic conditions of the moorlands, but even then, sheep-keeping remained largely limited to the moor-edge farms, particularly around Walshaw and Widdop. The 1851 census, for example, shows that out of 155 farms in the parish of Wadsworth, only eight were keeping sheep.

It’s tempting to assume that sheep-keeping was vital due to the importance of the local woollen textile industry, but in reality, the connection was minimal. While local sheep breeds may have supplied wool for weaving in earlier periods, as the market expanded, technology advanced and fashion trends shifted, the coarse, poor-quality fleeces of local breeds proved unsuitable. Instead, wool was imported from regions like East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire to meet the needs of the growing domestic weaving industry. Consequently, sheep-keeping in this area had little to do with the woollen trade that shaped its industrial history.

Pigs and Poultry

Pigs were not a major feature of the local farming economy. In the 1600s and 1700s, probate records indicate that only a minority of farmers kept pigs, with an average of fewer than one pig per farm. However, there was a modest increase in domestic pig-keeping following the repeal of the Corn Laws, as it became more feasible to feed pigs a portion of corn. Post-World War II, there was also a slight uptick in commercial pig rearing in the area, but it remained a small part of the farming economy.

Unlike pigs, poultry-keeping was far more significant in the Upper Calder Valley. The National Farm Survey, conducted during World War II, reveals that many farms, though not all, kept substantial numbers of poultry, with some flocks reaching into the hundreds or even thousands. In 1949, when there were concerns about flooding Hardcastle Crags for a new reservoir, evidence presented to defend the beauty spot claimed that the 18 affected farms produced an average of 14,500 eggs per year. This indicates the scale of poultry farming in the area at the time.

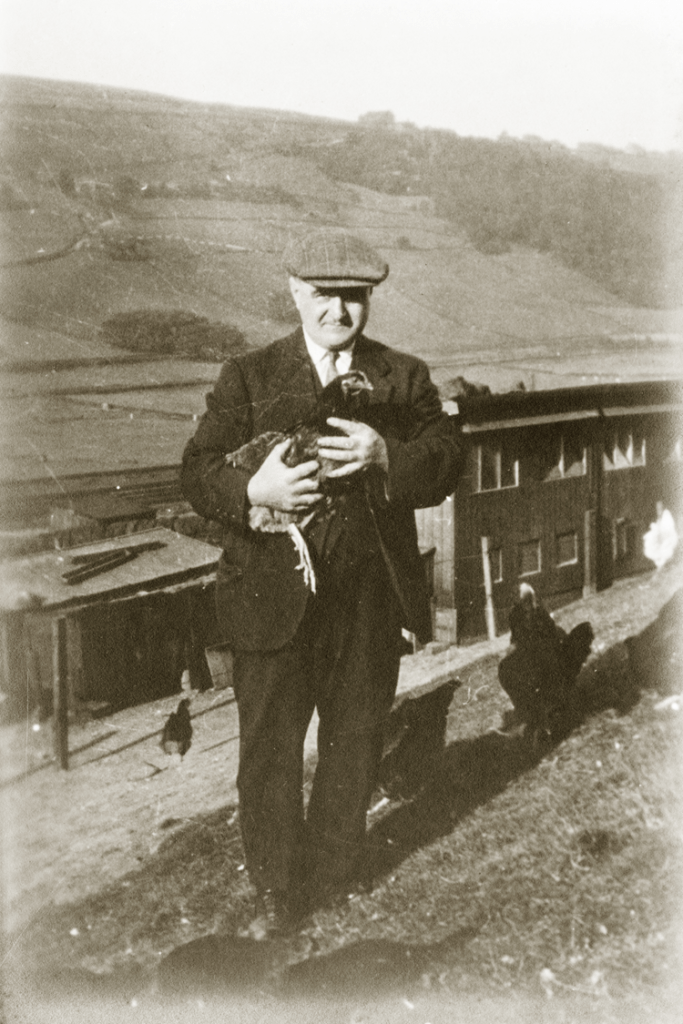

Poultry farming grew into a major industry in the 20th century. For instance, Lumb’s hatchery above Hebden Bridge Station was one of the many local operations.

Another notable commercial enterprise was located under Heptonstall.

However, the most significant poultry operation was the Thornber empire, which became globally important, producing millions of chicks in large brood sheds. The Thornber company didn’t just breed poultry; they also manufactured and exported battery cages worldwide. They produced millions of one-day-old chicks, which were delivered across the country within 24 hours, and employed around 1,500 people. This massive operation ran from the 1910s through to the 1970s but has since ceased to exist, marking the end of a once-thriving industry in the valley.

Arable Farming

Today, there is no arable farming in the Upper Calder Valley, but historically, this was a significant part of the agricultural landscape. The primary crop grown was oats, with small amounts of wheat and rye.

In earlier times, the local population would have relied heavily on oats, consuming them in the form of porridge and oatcakes, right through to the 19th century. Every farm would have had a few fields of oats, which were harvested with a toothed sickle and threshed in the barn using a flail. The threshing was done on the threshing stead, a specific area in the barn where the grain was winnowed in the through draft between two barn doors to separate the husks from the kernels. The kernels were then taken to the Lord of the Manor’s mill, such as Bridge Mill in Hebden Bridge, for grinding into oatmeal.

Every farm would have kept the oatmeal safe from pests by storing it in a special chest called an ark. They also had a bakestone, a flat stone on which oatcakes were baked, and a fleak, a rack suspended from the ceiling where the oatcakes would be hung to dry, much like washing. The straw left over from the harvest would have been used to feed livestock and horses through the winter months.

The prevalence of oats as a crop was highest during the warmer period between the 1100s and 1300s. However, even then, yields were low, with only two bushels of oats produced for every one bushel sown. As the climate cooled through the 17th century, yields continued to decrease. This decline in productivity likely contributed to the rise of the handloom weaving industry, as subsistence farming became less viable.

It seems likely that a form of convertible husbandry was practiced in the valley, where fields would alternate between oats and grassland in a rotation, lasting anywhere between three and twelve years. This rotation helped mitigate the rapid depletion of the soil’s fertility caused by arable farming.

As the network of turnpike roads improved, and the Rochdale Canal and the railway arrived, they allowed for the importation of corn, and oat-growing began to decline in the 19th century. By 1866, Wadsworth, with its 2,500 acres of enclosed land, had only eight acres dedicated to oats. By 1880, it seems oats had disappeared entirely from the landscape.

However, they made a brief comeback during the two World Wars. At this time, the government required farmers to plough up grassland to increase arable production. In 1942, for instance, this field above Rake Head on the edge of Erringden Moor was sown with oats. It just so happened that on the day I took this photo, the long grass resembled what it might have looked like in that long-ago summer.

After the wars, the practice quickly died out again, and there is no record of how successful the harvests were.

Vegetable Growing in the Valley

When it comes to vegetable growing, while market gardens could be found on the outskirts of towns in the lower valley, there was nothing of any substantial scale in the upper valley. Of course, allotments would have existed in the towns; below is an image of one on the site of Crown Street before it was built. However, there are no records of any commercial vegetable growing on the farms in the area.

Where vegetables are grown on farms in the valley, it is always for livestock fodder. There are still a few farmers around here who continue this practice. For example, I recently came across fields of forage brassica at Gib…

…and also fields of fodder beet, a cross between mangold and sugar beet, being grown at Owlers above Hardcastle Crags. These crops are not harvested, but rather the sheep are allowed in to directly consume the crop.

Potatoes were introduced to the Upper Calder Valley in the mid-18th century and became somewhat important, but crop returns from the 19th century show that only very small quantities were grown in each parish. For instance, in 1801, an account from Midgley mentions that each farm grew around two perches—about 16 yards—of potatoes, meaning they were primarily for personal consumption, rather than for commercial sale.

Insights from the National Farm Survey

The National Farm Survey, conducted during the Second World War, provides further insight into the crops grown in the valley. This extensive survey sent inspectors to all 300,000 farms across the country, requiring detailed returns on every aspect of farm life. One return for Higher Rawtonstall and Pry, near Blackshaw Head, which were farmed together as one holding at the time, shows that the farm grew four acres of oats and three acres of kale, alongside meadow and pasture land. The survey also records the farm’s livestock: 56 cattle, no sheep (it was still common for farms to have no sheep in the 1940s), some pigs, poultry, and two horses. It had just one worker.

The primary return provides extensive information about the farm, including a sometimes harsh assessment of the farmer’s abilities. For instance, a box marked ‘If personal failings, detail’ could include assessments such as ‘no arable knowledge’ or, at worst, ‘idle and obstinate’. However, no such assessment was made for the farmer at Higher Rawtonstall and Pry.

The survey detailed every field, with maps linking individual field numbers to their uses, with details of any crops grown in 1941, 1942 and 1943.

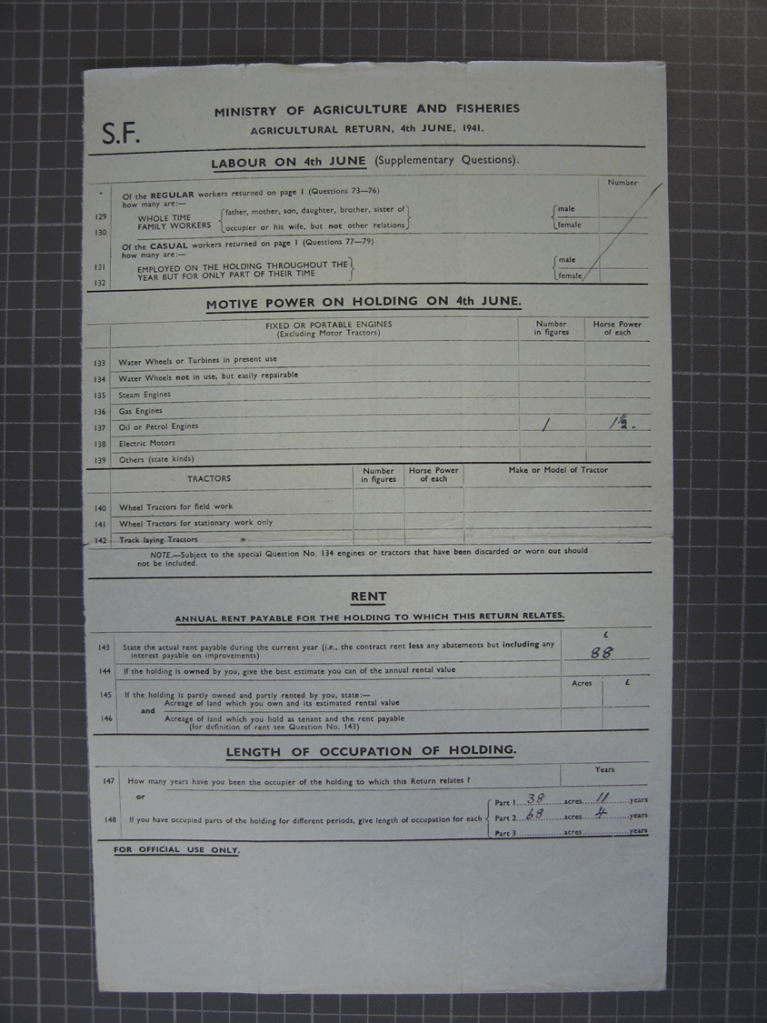

Supplementary returns included information on motive power, rent and length of occupation.

In addition, there is a horticultural return asking about small fruit and vegetables grown for human consumption. As shown in the survey for this farm, the response was ‘nil’. Indeed, of the roughly 400 farms I’ve examined in the valley, only three recorded anything other than ‘nil’ in the horticultural return. This suggests that in the 1940s, there was essentially no commercially grown fruit or vegetables in the valley for human consumption.

Honey

Honey was also a part of the diet in the Upper Calder Valley. Evidence of this can be found in the bee boles scattered across various locations in the valley. These small, sheltered enclosures were designed to house skeps—traditional wicker beehives. While honey would have provided a valuable source of sweetness in the past, its production would have been on a small scale, reflecting the self-sufficiency of the valley’s farms.

Common Fields in the Upper Calder Valley

Before the large-scale enclosure that shaped the landscape into the jigsaw pattern of fields we see today, the land was largely worked as open or common fields, also known locally as ‘town’ fields. These fields typically surrounded or were adjacent to the main ancient hilltop settlements, such as Heptonstall, Saltonstall in Luddenden, Midgley and Old Town. The town fields were divided into long, narrow strips, and some remnants of these strips are still visible in the landscape today, such as those below Old Town.

These strips were managed on a rotational basis, with some used for arable farming and other crops, and others for grassland. The rotation ensured the land’s fertility was maintained, and the strips would be alternately open or closed for grazing at various times of the year. The management of these fields was overseen by the manorial court, which regulated their use.

The Hay Harvest

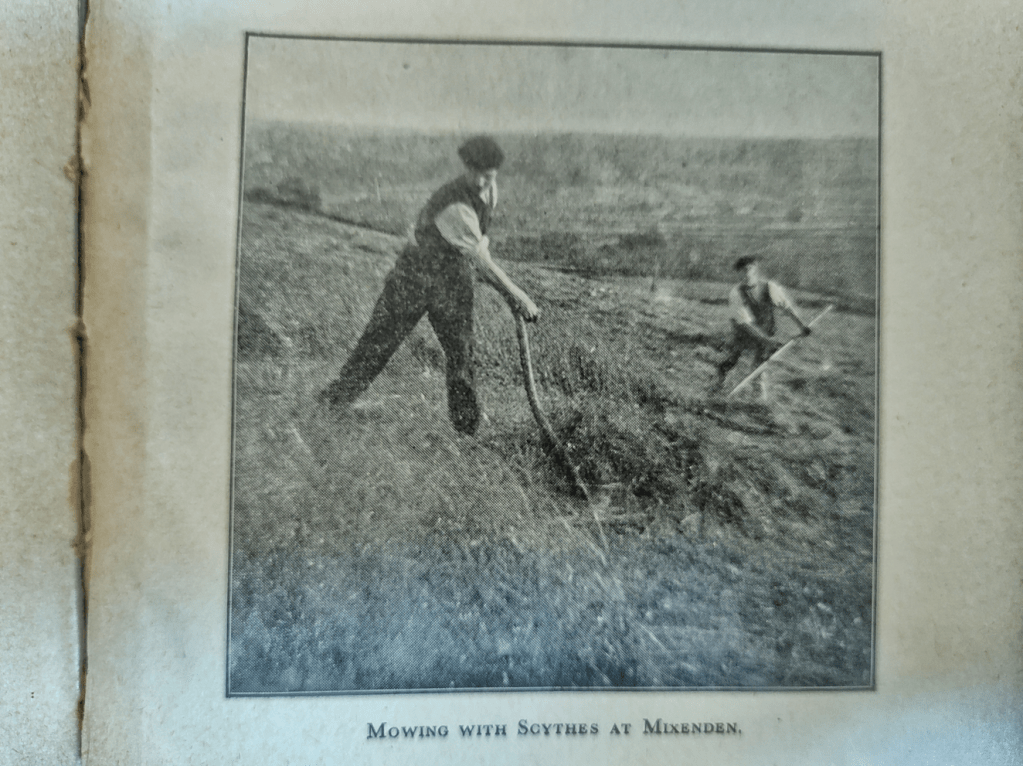

The upland environment of the Upper Calder Valley excels at producing grass, making the hay harvest the most significant event of the farming calendar. For generations, farmers have anxiously awaited breaks in the weather—a stretch of four or five days of settled conditions—to mow their meadows and dry the hay properly. This anxious wait and careful timing are still familiar to today’s farmers.

As the domestic handloom industry grew and flourished, farmers became too occupied with this work to handle the hay harvest themselves. A long-standing tradition emerged where Irish labourers, many of whom were farmers from County Mayo, came to the valley each summer to assist with the hay harvest. From mid-June through to mid-July, they would return year after year, often to the same farm, creating a familiar rhythm in the valley’s agricultural calendar.

The valley would have been buzzing with activity during these good weather spells, as everyone worked hard to get the hay into the barn and dried perfectly, ensuring it didn’t spoil or combust in storage.

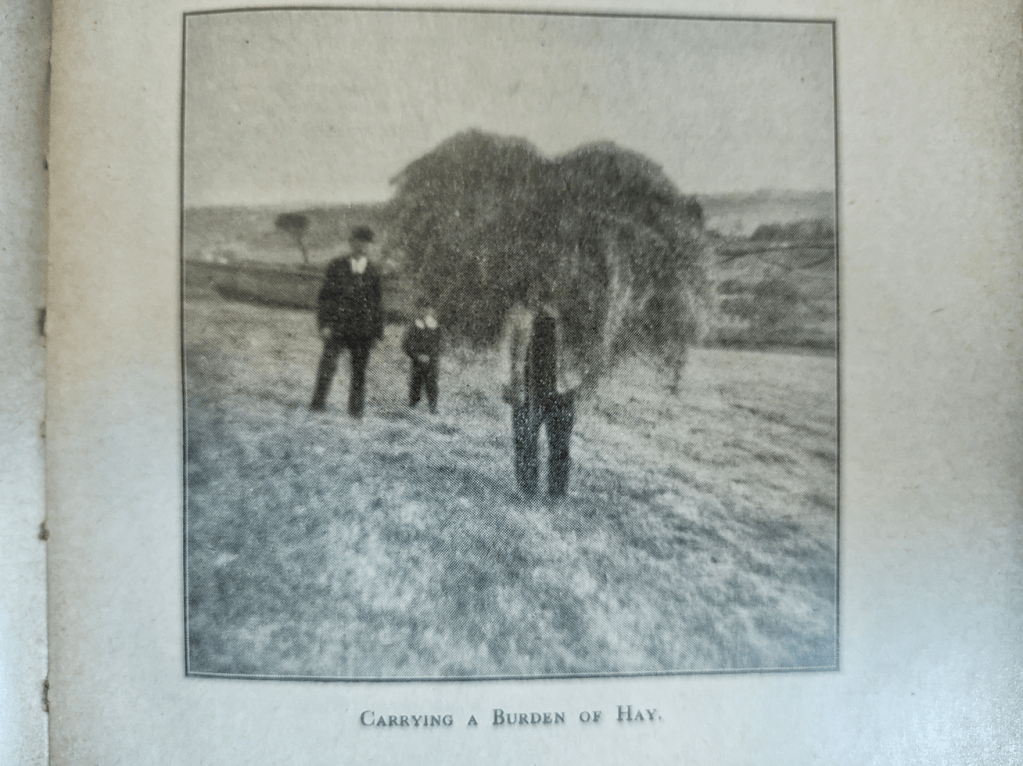

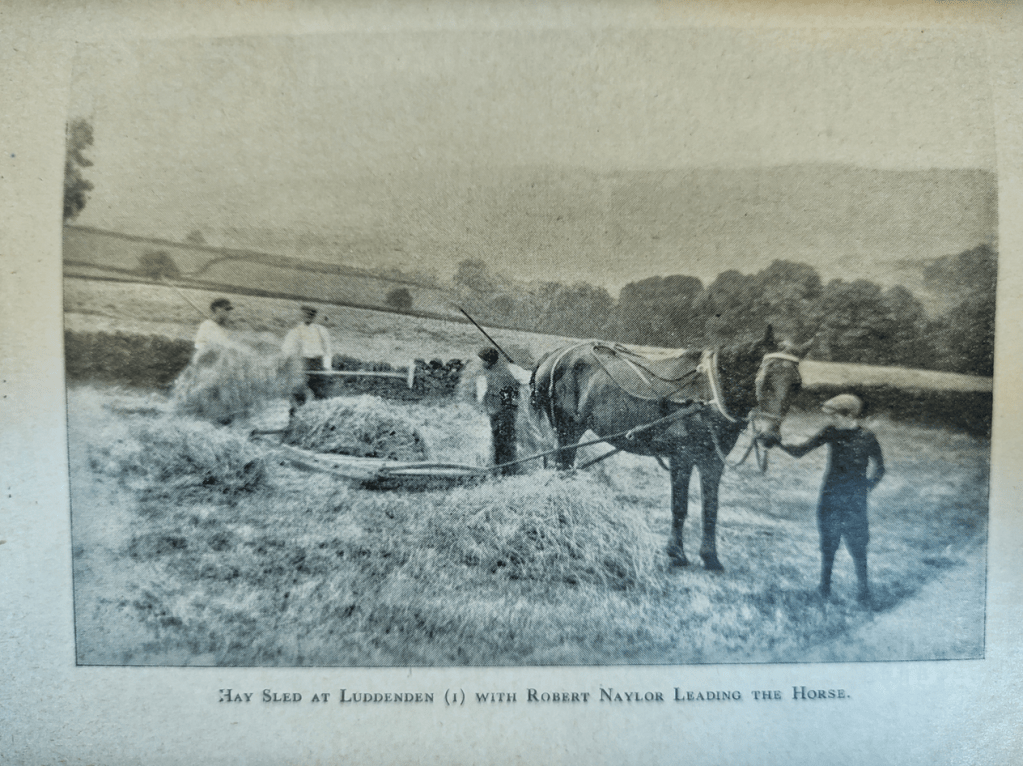

Transporting hay to the barn, once a significant task, was commonly done using a hay rope to carry it as a burden or a hay sled, either horse-drawn or person-drawn.

Eventually, the process was further mechanised with the introduction of baling. Today, modern forage harvesters handle the task incredibly efficiently, completing what was once a lengthy and physically demanding job with remarkable speed.

However, there’s a small revival of more traditional methods happening today at High Hirst Woodmeadow, where we’ve taken up scything. For the past three years, a small team of scythers has mown the meadow, giving us a glimpse of what it might have been like for those labourers from the past.

We also involve local children in the process of haymaking, because, after all, what are those long summer holidays for?

The Biodiversity of Grasslands

The last thing I want to emphasise is the incredible array of plant, fungal, insect and avian diversity that these fields have supported over centuries. The management of these permanent grasslands has been crucial in fostering this rich biodiversity. Any changes to the way these fields are managed will inevitably affect the species that thrive within them. This diversity isn’t here in spite of the land’s management—it exists because of it.

I hope this exploration of farming’s history provides context for discussions about where the valley’s landscape goes from here. Understanding the intricate relationship between the land, its management and its people helps us appreciate the delicate balance that has been sustained over centuries. This history is not just a record of the past but a guide to the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. As we face pressures from climate change, biodiversity loss and shifts in farming practices, reflecting on the lessons of the past can inform more thoughtful decisions for the future. The choices we make now will shape the legacy we leave behind, ensuring the valley remains a rich, thriving and resilient landscape for generations to come.

This article is an adaptation of a talk I was invited to give in September 2024 at an event called ‘Save Our Soil’. Organised by the Calderdale Ecological Land Trust and held at Hebden Bridge Town Hall, it proved to be a fascinating day, with talks from ancient grassland fungi expert Steve Hindle and soil scientist Charlie Clutterbuck, stalls from local food producers, and a panel discussion on food sovereignty with environmental justice campaigner Leonie Nimmo, local farmer Ann Jones and agroecological consultant Darren Roberts. In my talk, I aimed to provide the historical context for our deliberations about what might be possible in the future by looking at what had been achieved by way of local food production in the past. Thank you to Sue Mellis and Jenny Slaughter for the invitation, which provided me with the impetus I needed to draw my years of research, which I had scattered among the 128 posts on this website, together into a coherent story.

Among and in addition to the authors listed in the bibliography below, I’d like to thank the following local historians who have been particularly helpful: Nigel Smith, Keith Stansfield, David Cant, Diana Monaghan, Heather Morris and Peter Thornborrow, and to Ann Kilbey for supplying the images from the Pennine Horizons Digital Archive.

Most of all, I would like to thank the farmers who have generously taken the time to share their knowledge with me over the years. Through their stories, I have gained a deeper understanding of this landscape and how they uphold and adapt the traditions that have shaped it. Their insights have been invaluable in connecting the past to the present and highlighting the enduring relationship between the landscape and those who care for it. In particular, I’d like to thank Allan Midgley; Ann Jones; Bruce Kenworthy; Carl Warburton and Sandra Evans; Chris, Kath and Paul Miller; David Ingram; David Pratt; Dick Baldwin; Ed Sutcliffe; Eleanor Logg; Fiona and Andy Gibbon; Gordon and Miriam Whittaker; Ian and Rachel Pratt; Joanne Redman; Julie Greenwood; Luke Westall; May Stocks; Peter Logg; Roger, Rosemary and Jack Butterworth; Spiros Spyrou; Tony Ingram; and Trevor and Anne Shackleton.

All uncredited photos are my own. Some people have asked me if I used a drone to take some of them, but no, my feet were planted firmly on the ground and the camera in my hand when I took them. My camera is nothing special, but it does have a good zoom, so when I take photos from high ground looking down it can look like they were taken from a drone.

Bibliography

Pennine Pespectives: Aspects of the History of Midgely, edited by Ian Bailey, David Cant, Alan Petford and Nigel Smith, 2007.

Field and Yard, Bernard Barnes, Pennine Heritage, 1983.

Todmorden People: A celebration of local folk 1973–1996, Roger Birch, edited by his son Daniel Birch (many of the photographs which make up the ‘Farmers’ section of the book are viewable at Top Brink Inn).

Traditional Food in the South Pennines, Peter Brears, 2022.

‘Revealing a New Northern England: Crossing the Rubicon with Daniel Defoe’, published in the journal Prose Studies: History Theory, Criticism, Stephen Caunce, 2007.

Erringden, Langfield and Stansfield Probate Records 1688–1700, edited by Mike Crawford and Stella Richardson, 2015.

Heptonstall and Wadsworth Probate Records 1688–1700, edited by Mike Crawford and Stella Richardson, 2020.

The Little Hill Farm, W.B. Crump, 1951 (republished by the Hebden Bridge Local History Society in 2023).

The Diaries of Cornelius Ashworth 1782–1816, Richard Davies, Alan Petford and Janet Senior, 2011.

Industrial Landscapes, David Ellis, Pennine Heritage, 1983.

‘A Pennine Worsted Community in the Mid-Nineteenth Century’, published in the journal Textile History, G.A. Feather, 1972.

Setting the Scene: An Introductory Outline to the Man-made Landscape of the South Pennines, David Fletcher, Pennine Heritage, 1982.

A Hilltop Community and the Changes in a Lifetime (early unfinished draft), Mary Gibson.

Flock books of the Pennine Sheepkeepers Association, summarised for me by Mary Gibson.

The West Yorkshire Moors: a hand-drawn guide to walking and exploring the county’s open access moorland, Christopher Goddard, 2013.

Enclosing the Moors: Shaping the Calder Valley Landscape Through Parliamentary Enclosure, Sheila Graham, 2014.

Early Trackways in the South Pennines, Margaret and David Drake, Pennine Heritage, 1983.

Crimsworth Dean, Pecket Well and Hebden Bridge: A Bit of Local History, W. Stanley Greenwood, 1987.

Oxenhope: The Making of a Pennine Community, Reg Hindley, 2005 (particularly chapter 6, ‘Farms and Farming Since 1800’).

Pennine Valley: A History of Upper Calderdale, edited by Bernard Jennings, 1992 (particularly chapters 4, ‘Farming and the Medieval Landscape’; 6, ‘Land and Society in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries’; 8, ‘The Age of the Yeoman Clothier’; and the subsection on agriculture in chapter 13, ‘Economic Life Between 1836 and 1914).

Born to be a Farmer, Edgar Lumb, 2000.

Mount Tabor Farmer, Edward Lumb, 2010.

The Fabric of the Hills: The Interwoven Story of Textiles and the Landscape of the South Pennines, Elizabeth Jane Pridmore, 1989.

A History of Crimsworth Dean, J.D. Smith, 1972.

‘Farming Before the Nineteenth Century’, Nigel Smith, published in Pennine Perspectives: Aspects of the History of Midgley, edited by Ian Bailey, David Cant, Alan Petford and Nigel Smith, 2007.

‘The Location and Operation of Demesne Cattle Farms in Sowerby Graveship circa 1300’, Transactions of the Halifax Antiquarian Society, Nigel Smith, 2007.

‘Cruttonstall Vaccary: the Extent in 1309’, Transactions of the Halifax Antiquarian Society, Nigel Smith, 2008.

‘The Medieval Park of Erringden: Creation and Extent in the Fourteenth Century’, Transactions of the Halifax Antiquarian Society, Nigel Smith, 2009.

Settlement and Field Patterns in the South Pennines: A Critique of Morphological Approaches to Landscape History in Upland Environments (PhD thesis), Nigel Smith, 2013.

History in the South Pennines: The Legacy of Alan Petford, edited by Nigel Smith, 2017.

‘Haymaking in Colden’, published in the Hebden Bridge Local History Society Spring 2020 newsletter, Keith Stansfield.

Vernacular Architecture in a Pennine Community (MA thesis), Christopher Stell, 1960.

‘Pennine Houses: An Introduction’, Christopher Stell, published in the journal Folk Life, 1965.

History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax, in Yorkshire, John Watson, 1775.

The Laithe House of Upland West Yorkshire: Its Social and Economic Significance (PhD thesis), Christine Westwood, 1986.

Other Resources

1841–1921 Censuses

From Weaver to Web: Online Visual Archive of Calderdale History, https://www.calderdale.gov.uk/wtw/

History of Widdop, https://www.widdop.info/, John Shackleton

Jack Uttley Photo Library, www.fieldhead.net

Land Valuation Survey, 1910–15

Malcolm Bull’s Calderdale Companion, http://www.calderdalecompanion.co.uk/

National Farm Survey 1941–43

Ordnance Survey Maps, viewable at the National Library of Scotland map images site, Six-inch maps 1842–1952 (https://maps.nls.uk/os/6inch-england-and-wales/), 25-inch maps 1841–1952 (https://maps.nls.uk/os/25inch-england-and-wales/)

Pennine Horizons Digital Archive, https://penninehorizons.org/

‘Settlements, Buildings and Fields of the Upper Calder Valley’, Nigel Smith, https://settlements.hebdenbridgehistory.org.uk/map

This is a remarkable research of the farming history of the area Paul. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it and have sent it to friends. xx

LikeLike

An absolutely brilliant piece of work, Paul, accompanied by some amazing photography. It draws on such a wide variety of sources, and challenges some assumptions while explaining many interesting farming features interesting to help put our own work in a proper historical perspective!

Neil Diment (Friends of High Hirst Woodmeadow)

LikeLike

Paul this is a wonderful piece of work to have researched and brought this history together. A wealth of infirmation and a such an interesting read. Not to mention your lovely photographs.

And I hope too, as you say, that it will enable informed choices as the Upper Valley tries to get to grips with the challenges and opportunities (diplomatically put!) ahead.

LikeLike

Just a stunning piece of work , you should be very proud of your achievment !

LikeLike

Thank you, Bob. Very kind.

LikeLike

As a child I roamed those hlls , stone horse troughs with ice cool water .

I had a friend who lived on a farm , she had a pet magpie and flagstone floors .

Doughty farm …I looked for it but it seems to have gone .

Again thanks for your work

LikeLike