Here we are again, my boy, like so many times before, emerging from the frosty morning shadows of the deep valley and its woods, out and up into golden morning sun, with the promise of a beautiful, memorable day before us. We’ve certainly picked a fine day for our quest to follow Crimsworth Dean Beck to its source on the moor. We like an expedition like this, don’t we? We like there to be something to reach or hunt for or witness – a river source or a ruined old farm, curlews arriving or swifts leaving, conkers or prehistoric cup-and-ring marks, a full moon rising or a solstice sunset. Coming up with ways of making walks into mini adventures has been one of the many unexpected ways in which having you as my companion on almost every walk has made them such fun.

Sorry I had to get you up so early. It’s not long past midwinter, so the day will be short and I don’t want us to get benighted on the moor, although we should do that on purpose one day soon. But you always surprise me at how uncomplaining you are when we have an early start, whether it’s to fit in a walk on a weekend morning before you go swimming with mum in the afternoon, or a dash along the canal towpath to the railway station for a day in the Peak District or the Dales or the Lakes, or leaving a little earlier for school to climb the hill for a winter sunrise, or, like today, where we have an expedition planned that will need every daylight hour on offer. I can only remember you properly groaning once, but that was when I woke you at 3.20am last May to climb above the woods for the dawn chorus, so that was entirely fair enough. We still talk about hearing all the valley come alive with song, though, so I reckon it was worth it. I think today is going to be worth the early start, too.

I love the way you laid down and put your ear to the pipe at the Aqueduct Bridge back there. I’ve always droned on about the history of this landscape on our walks, although I don’t expect you to remember much of it at all. But you take some of it in, in your own way. You’ll listen to me tell you about John F. Bateman’s amazing 10-mile-long conduit that got the water from his new reservoir at Widdop all the way to Halifax in the 1870s, but you want to see if you can hear the water whooshing through, so down you lay. But in any case, I don’t bore you with all the history – or, for that matter, pointing out and naming all the birds and wildflowers and insects and trees – in the expectation that you’ll take it all in, or that nature and the outdoors will become your ‘thing’ in years to come, but so you can see what it is to be enthused about something, to be fascinated by your surroundings, and to love the extraordinary world we find ourselves in.

Oh look, there’s someone outside at Outwood. I’ve just got to stop and see if she knows her lovely old farmhouse is the subject of some of Peter Brook’s finest paintings. I’ll try not to spend too long chatting. I was going to say I know it must be boring at times standing around while I talk, but you always seem to find some way of entertaining yourself – kicking a ball for their dog, or digging around in the track (you found a very old coin once when we talked to Alan near his farm), or swirling the water around in a puddle, or raiding my rucksack for a snack. You never complain and are always so patient, which means so much to me, because it’s the hundreds, the thousands of conversations I’ve had with farmers and walkers and everyone else we bump into when we’re out and about that I have learnt so much about this place. And they’re often interested in you, anyway, and where we’re off to and how far we’ve come. Although I’ll admit there was one time I did get too deep in conversation with David at Pry about his cattle and his curlews, and I failed to notice that the bitter November dusk had sunk deep into your bones, and we had to ring ahead for mum to run you a bubbly bath and we ran home through the dim fields and the darkling woods.

Oof, that was a nasty fall. Let’s get you up and over to this wall. Not hurt, but spectacularly covered in mud. Let’s get some of this moss and clean you up. You’ll soon dry out in this sun. That was unusual for you to have a fall – you’re as sure-footed as a mountain goat, which you have to be to not regularly slip and slide over on all our muddy walks, let alone to swarm over the rocky spine of Striding Edge up to Helvellyn like you did. But we’re always prepared with some spare clothes in case we teeter into a stream, although I can only remember once having to use them, when you stepped in a bog on our way up to the source of the Colden Water three years ago, and your wellie filled with water. We sat beside the ruin of Crabtree Field and watched a barn owl ghost across the valley while we changed your socks. That’s the great thing about neoprene wellies, which we’ve both always worn for almost all our walks; it doesn’t much matter if they get wet inside, and of course they keep your feet toasty warm however cold it gets. And we always have our waterproofs and woolly hats and scarfs and big gloves in winter, and sun hats and suncream and plenty of water in summer, and of course you’re never without your most essential piece of equipment; your stick. What would we do without your stick? Or sticks, I should say. You’re on your third seasoned hazel with a deer antler handle now, all made by Roger, all bought from him on our annual trip to the Malhamdale Agricultural Show. He recognises you as one of his best customers every year now, as not only do you wear your sticks down with all the miles but, unlike most of his other customers, you’re still growing, meaning you need a new one twice as often.

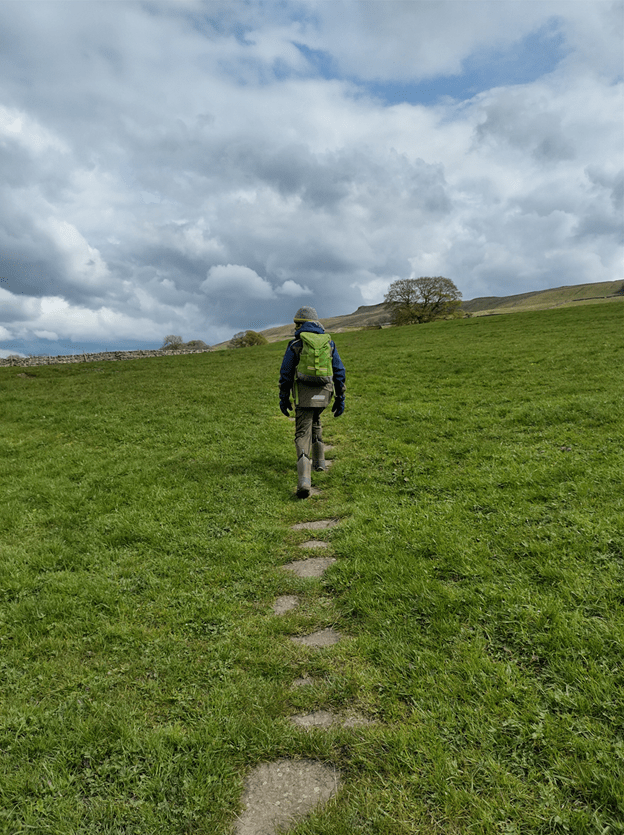

We’re making good progress here. We’ll soon be on the moor and off all the paths, as very few people must ever go where we’re going. While we’re on this track, though, just walk ahead for me for a minute, right in the middle. That’s it. It’ll make a great photo. Right, you can come back and finish breaking the ice in that puddle now. Sorry I interrupted. It’s just that there’s nothing like a figure striding off into the landscape to make a great image. But these photos hardly reflect what walking with you is really like, as you’re rarely calmly walking along in the middle of the path. I do also take photos (albeit in them you’re mostly a blur) of what you’re really up to on our walks – sword fighting with imaginary opponents with your stick, jumping over and into puddles, firing rushes from your shoulder like a bazooka in that clever way Dan showed you, scooping up green gloopy weed from ditches with your stick and flinging it into the sky, pelting dry stone walls with snowballs, skimming stones in streams, collecting feathers, pebbles, pine cones, oak galls and sheep fleece snagged on fences and stuffing it all in the mesh pockets of your rucksack, investigating every nook and cranny under boulders and amongst tree roots, and generally tirelessly, insatiably getting to know this landscape in a way that makes my efforts – which pretty much just involve walking along and looking at it – seem feeble. There’s me thinking I’m trying to teach you about how to connect with nature. It’s really the other way round.

I did not know that about the Ghostbusters’ proton packs. Where did you learn about that? You tell me so many interesting things on our walks, about obscure spells in the Harry Potter books, or the finer points of TIE Fighter engineering you’ve gleaned from your Star Wars encyclopaedias, or the troubles of Greg in the latest Diary of a Wimpy Kid, or your updated design for the most effective battle armour. I have noticed that you become particularly enthused about these sorts of things soon after I’ve deployed the most sugary treat I have stashed in my bag, which I always save for the most auspicious point of our walk. Indeed, you did just have a Crunchie back there at the point where we declared the source of Crimsworth Dean Beck to have been found. You earned it, and then some, stumbling for miles across trackless heather and bog and hidden boulders, as all our river source adventures – the River Calder, the Colden Water, Cragg Brook, Walshaw Dean Water, Luddenden Brook, Hippins Clough, Hebden Water – always end up. But I like it when you get in super chatty mode. You sometimes apologise for talking too much if you sense, as is sometimes sadly true, that I’m not really listening. But it’s me that should be saying sorry. Sometimes I’m only absently listening because I’ve got my eye on the time, or the black clouds massing at our backs, or the fork in the path coming up, or the bus we’re aiming to catch, but sometimes my mind has wandered off onto something else entirely, like how we’re going to find someone reliable to fix the roof, or why I lost touch with that friend 20 years ago. Adult minds are like that, and not just because we have responsibilities and regrets and worries, but also simply because we’re hopeless at staying in the present. But you, you’re always in the moment, and you always bring me back to it. It’s another unexpected reason why it’s so much better to be walking with you than on my own. But you want us to play a game now? Of course we can. What do you want to play? Connections? Random Words? Word-At-A-Time Story? Just a Minute? We do love a word game on our walks, don’t we? They generally become more surreal as they go on and descend into fits of giggles, but they help spur us on, especially if we’re flagging. Connections it is. You start.

Look, you can just make out the green of the Brontë Bus going down Keighley Road. That means we’ve got an hour to get across this last stretch of moor before the next bus. Urgh, it still seems like a long way, and looking at the map, it’s made up of three separately named swamps. That doesn’t sound good! And if we miss it we’ll be stranded waiting in a very bleak place for another hour, and by the time the following one comes along it will be dark, and it won’t be expecting anyone to be there and might drive right past. Let’s think. We could go north down to the Waggon and Horses and catch the next bus there, like we did a few months ago. But look, the sun’s about to drop back out of that cloud bank. If we go down on the north side of the moor we won’t see it again today. What about heading south, down the Haworth Old Road? And that gives me a great idea. We could nip onto the 595 when we get to the bus stop, and get off at the Robin Hood for a swift half of Appeltiser and a packet of crisps and a sit by the fire for half an hour before hopping on the next one back down to town. That would combine two things that have often been features of our walks – use of buses, and a little stop somewhere for a smackerel of something, which never goes amiss on a walk, does it? We’re rather spoiled for choice around here and have always made use of our options. Think of all those times we’ve hopped on the 596 for a pop into May’s Shop for some sweets and then up for a bluster on the moor, or jumped off the 595 for a warm up and a cake in the cosy cafe at Old Town Post Office, or slurped up sticky toffee pudding in the Packhorse Inn in the middle of a hike in the high hills, or trundled along on the 574 for a salted caramel milkshake at Bob’s Tearoom to power us along a walk in Luddenden, or emerged from a trek through the woods at Gibson Mill for a hot chocolate, or heaved ourselves up to Ann’s Honesty Box at Old Chamber for some Just Jenny’s ice cream, or bemused the Brontë Bus drivers by getting off in the middle of nowhere and heading for the horizon, or earned one of Lynn’s flapjacks after a climb up out of Jumble Hole to the Great Rock Co-op, or stopped in at Craggies Farm Shop, mostly getting up there on the 901 for a walk on Manshead Hill, but once for an early dinner about 17 miles into your record-breaking 24-mile trek. Goodness, thinking through all those makes it seem like all we ever do is take buses to somewhere we can scoff cake, although we know we’ve always earned it. But most of the time we make do without wheels and carry our own goodies.

And it’s not all pleasure, is it? We set you to work in this landscape as well. You’ve planted trees with Treesponsibility at Blackshaw Head and with Forus Tree at Lumb Bank, collected acorns for The Northern Forest in Hardcastle Crags, you’ve bashed balsam in Stoodley Glen with the Calder Rivers Trust, you’ve built leaky woody dams with Slow the Flow in Hardcastle Crags and Crimsworth Dean, you’ve tedded and baled hay at the High Hirst community meadow and coppiced hazel and built fascines in its neighbouring woodland, you’ve created wildflower meadows on your school playing fields, you’ve surveyed for birds for the RSPB and butterflies for Buglife and fungi for with the Ancient Grasslands Project, you’ve litter picked with the Friends of Hebden Bridge Station and in our own neighbourhood and all over town with your school, you’ve tended community vegetable gardens with Incredible Edible, you’ve mulched fruit trees in the Blackshaw Environment Action Team’s community orchard, you’ve raised hundreds of pounds for Curlew Action by doing a sponsored walk, and just the other day you were up to your neck in mud at Brearley Fields wetlands reserve helping create a new sand martin nest wall with members of the Calderdale Bird Conservation Group. We get a lot out of this place, but I’m proud that you’re always enthusiastic about putting your share back.

That was lovely coming down Thurrish Lane into the sunset. It’s going to disappear over the shoulder of Shackleton Knoll any moment. I’m glad you were up for this idea, even though it will add two and a half miles, on top of the nine we’ve already done. It never ceases to amaze me at how you cheerfully accept more miles. By my reckoning you’ve done nigh on 500 walks since you were about three years old – proper walks, that is, on muddy paths and up hills, of which we did about 40 a year when you were three and four and five, and have been doing around 80 a year since you were six – from our frequent mile-long bolts up to the gate above the woods or extended walks home from school once a week, to many day-long expeditions like today, and everything in between. Even if our average is three miles, which seems about right (it was more like two miles when you were three, and more like four or so on average nowadays), that means you’ve walked 1,500 miles – that’s Land’s End to John O’Groats, and then back again to Edinburgh. But those are just the proper walks. You walk everywhere, since we’ve never had a car. You walk 300 miles every year just to and from school, although even that daily journey we make into a walk by getting up the hill and into the woods away from the horrid main road. And then there are the walks into town, two miles there and back, which we do twice a week on average; that’s another couple of hundred miles a year. So between our proper walks (about 300 miles a year nowadays), the school run and getting to and from town, your legs have carried you at least 5000 miles so far. That would get you to India. So no wonder you’re used to it and never complain. And as for the climbing, the elevation, the sheer amount of hill you have hauled yourself up! Pretty much all our walks involve a sharp ascent up these relentlessly steep valley sides, and then yet more up as we traverse the tops and the moors, and plunge down into and back out of cloughs. Even our very shortest walk up to the gate has us climbing nearly 400 feet. Your school run always involves over 500 feet of ascent, and our longest expeditions like today have us doing over 2000 feet of ascent. If the average on our proper walks was even just 600 feet, and then adding the school run and the little bit we have to do on our way home from town, do you know how high you have climbed? Seven hundred and fifty-four thousand feet. That’s 143 miles. You won’t know what that means. I didn’t when I worked it out. Well, let’s put it another way. That’s 26 Mount Everests, one on top of the other. It’s up beyond the troposphere, and the stratosphere and the mesosphere, way beyond the Kármán line, which at 62 miles is where astronomers generally agree space begins. If we could have added all your steps upwards together, they would have propelled you well into the thermosphere, into low earth orbit with the satellites. You could have touched the aurora borealis.

Putting those upward steps together and being up there among the Northern Lights does sound pretty cool, but I wouldn’t trade it for all the wondrous things we’ve witnessed on our walks: cloud inversions at dawn and Jupiter winking on in the twilight, waterfalls in secret ravines and standing stones on lonely hills, spring lambs just born and the cattle being brought in for milking and the sweet scent of the hay being baled in summer, icicles as long as your legs in forgotten quarries and wind-sculpted snowdrifts banked against the pasture walls, buzzards flying through rainbows and deer bounding away into the woods, sun rays piercing through clouds in the last moments of grey days and blue skies that go on forever over the high moors. I have wished, on so many days, that our walks could go on forever.

Going, going, gone. Yes, that’s right: because I’m a bit taller I could see the sun as it set for a millisecond longer than you. Don’t worry, though, I’m not going to keep that advantage for much longer, the rate your legs are growing. It’s going to get cold very fast now. But I love striding on into the dusk, especially if it’s with you. And look at that sky. If only we could nip across the valley and up that hill the sun just slipped behind, the one strangely called Hamlet, we could get an even better view of the sunset. And from there you get such an amazing 360-degree panorama of the whole of our world. I mean, we love going further afield and seeing new places – we always look forward to travelling up on the Settle–Carlisle line to Garsdale and getting the Little White Bus to Hawes in Wensleydale for our annual autumn stay in the Dales, and we’ve had some fantastic adventures on the high Lakeland fells, and one day we’ll take you up to the Scottish Highlands for higher and wilder summits yet. But from up on Hamlet we can see the swell of the 40-mile length of moorland horizons that encircle and define our patch of the Pennines, and you’ve tramped over them all, and within the 80 square miles contained within them, you’ve walked thousands of miles. But aren’t we blessed that even though we’ve delved into so many cloughs, wandered along so many lanes and bounced over the bog and heather of so much of these wide open moors, there are so many paths we have yet to pace, so many streams and crags and woods still to explore, and so many places we have only passed through in one season, or at one time of day, or in one kind of weather? In the years ahead, we’ve so many more miles to tread together in these hills. But one day, you may choose to live amongst other horizons. Who knows where life will land you? You are just at the beginning of your adventures, with so far to go – but even the longest journey begins with the first step. I hope these walks, your first steps, will stand you in good stead, that they are teaching you the determination to tackle the steepest climbs, the resilience to keep on going when you are weary, how to find your way when the fog comes down, and the value of stopping once in a while to appreciate the beauty around you. And I hope that wherever you end up, you’ll always come back and walk these green hills of home with me.

A few from walks we have done since this post was published:

What a beautiful tribute to your son!

LikeLike

Thank you, Stella.

LikeLike

What a BEAUTIFUL piece!

You and your son are very lucky to have each other.

LikeLike

Well, I know I’m lucky. Thank you, Stella.

LikeLike

This is beautiful. I have a 14 month old daughter and I look forward to adventures like these 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you, Tom. It might seem a way off still, but it comes sooner than you think.

LikeLike

superb, thank you., so many of those thoughts fli through my head - especially adapting the route to catch the next bus , working out can i get there and back and persuading my (the) wife that it is sensible to cross that swampy bit,… oh the arguments after she got stuck,

thanks again and the great photos up on the south Pennine landscape i love to roam too

LikeLike

Thank you, Ian. Glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

This is beautifully written and is a wonderful record of your adventures with your son. You write so well from his point of view! I did a lot of travelling with my children when they were small and they travel continues to be a big part of their lives whether it’s exploring ghost towns in the California desert or being air vacced from Everest base camp! As you write – you don’t know where this will lead with your son.

LikeLike

Thank you, Heather.

LikeLike