At dusk on the penultimate day of the unprecedented September heatwave, small sounds are swallowed in the muffled dimness of the valley side woodlands: the purring ‘seep’ of a treecreeper, a squirrel’s peculiar throaty grunting, the patter and slap of acorns prematurely falling. After shielding and shading from the blaze of the day, the canopy now cradles the sticky heat. But up in the pastures under the open twilight sky, the air is finally cooling. Hay bales are awaiting collection in the last meadow to be mown at Cruttonstall; the Butterworths are busy gathering in their bales at Scammerton, their cattle unmoved by the tractor’s activity in the neighbouring field; and across the Colden Valley below Great Lear Ings, Stephen’s black-wrapped bales are jet beetles huddled in small herds for the night. As peach-topped cumuli tower over the moors, sounds are magnified in the almost-still air: the bark of a dog, the laughter of children playing out late near the village school, the ricochets of jackdaw calls from a roost in the clough, the trickle of water into a stone trough under a copse of sycamore.

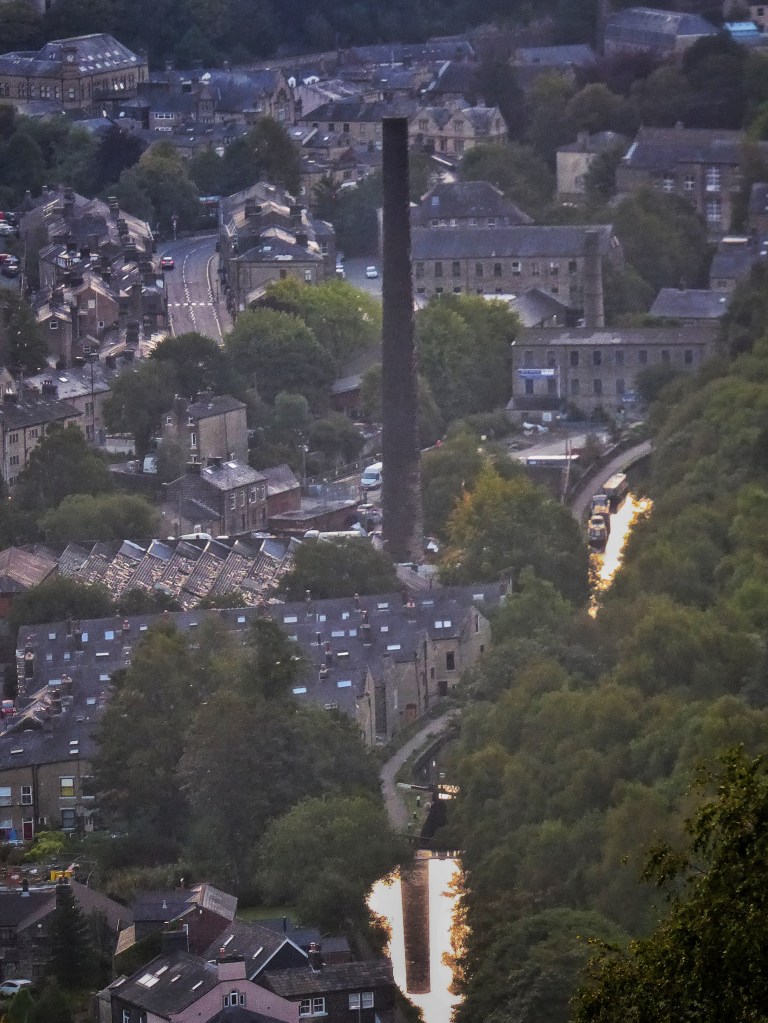

The following dawn, the upper reaches of the valley exhale a mist. It becomes the glacier that never made it beyond the Cliviger Gorge, moving downstream at a glacial pace, lapping into Stoodley and Parrock and Jumble Hole and Beaumont cloughs, but melting as its snout is squeezed between the Calais and Dover hillsides. In Hebden Bridge, unaware it was nearly shrouded, other than the flashing amber of the Belisha beacons at the Co-op zebra crossing, all remains quiet and still for now before the heave of tourists arrive for the day. The meadows that were cut a week ago at the beginning of the heatwave, having been starved of rain since, have remained fawn, but this morning they are sheened and greened by dew. Siskin, bullfinch and chaffinch call in their closely-related dialects from within the hazel coppice at Turret Brink. A wood pigeon and a pheasant meditatively wheeze and cluck from above the boulder-strewn wood at Ferny Bank, and the sun breaks free of the moor above a wedding marquee erected near the ruin of Johnny House.

After two days of rain and cooler temperatures, the fluttering of sycamore leaves into the Hebden Water above Foster Mill Bridge and the smell of decaying balsam brings this September much more in line with its predecessors. Beside the river path, over the locally-rare field boundary of a traditionally laid hedge, the arrows of the White Rose archers are thudding into wicker targets scattered on Salem Field, and upstream, beyond the allotments that have colonised the former sludge beds and settling tanks of a sewage works, the weir beside the Hebden Bridge Bowling Club is in good voice. A chiffchaff, imminently leaving for southern Europe or Africa, calls a farewell at Upper Lee.

The rarely-grazed long grass of the pastures in Middle Dean are saturated and sparkling with dew, with the larger lilac and yellow jewels of devil’s bit scabious and hawkweed among the rainbow of crushed diamonds. Between the hanging beech woods – recently thinned, with crates of logs ready to stock local woodsheds in preparation for winter beside the track – and the rushing waters of Bridge Clough, open-grown ash and oak lend the space a parkland air. The ash has already started shedding its leaves around the old leaning stone gate stoop at its base, and a dragonfly lands in the canopy of an oak.

Upstream further, where the three-mile tributary valley becomes known as Crimsworth Dean, house martins by the hundred swirl above the ruins of Nook and Lower Sunny Bank. As if paranoid that these strict aerial insectivores have designs on their own dietary requirements, a chattering charm of goldfinch frantically lay claim to a birch beside the rush-clogged track of Sunny Bank Road, and while continuing to vigorously gossip, lever the tiny winged nutlets out of the tightly-rolled catkins, leaving the fleur-de-lys bracts to fall, as they already have been without this kind of help lower down in the valley. A stoat furtively crosses the track beside Nook, and at Lumb Falls below, a group of students from Manchester University are laughing and lunching together on the rocky ledge beside the torrent. Oblivious to all this, a skein of 80 pink-footed geese, fresh in a day earlier than last year from Greenland or Iceland, where they have been since March, bugle eastwards.

The fields enfolded by the moor at the head of the valley, an inheritance from centuries of stewardship, are green and still growing. Bales are being collected below Broadshaw, and a tractor is spreading lime below Bedlam, raising the acidic soil’s pH value to promote greater productivity, reducing the need to buy in grain for winter feed. The few farming families that still tend these acres, some of whom have a centuries-old connection to their fields, will have difficult decisions to make in the coming years, balancing the increasing environmental demands of society against the marginal economics it forces on them. But coaxing a livelihood from this land was ever a struggle. As the trumpeting geese have heralded today, winter is coming.

Love the cloud bursting like trails from a firework in the photo after “ascending Pry Hill” Wouldn’t be lovely if you could add some of the sounds you so delightfully describe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Ann. It was a strange cloud formation. It was a quietly spectacular evening.

I haven’t looked into whether I can add audio recordings. I know I can’t add videos, at least not on the basic WordPress plan I am on. Thanks for the suggestion.

LikeLike