The Callis Wood birches are bowing out of autumn early; having shed their leaves in the past weeks, they have faded to an ashen, winter-ready grey. Among them, though, the beech are beginning to blaze. Fleets of red admirals marshall on the buddleia in the soft sun, though the watery light belies the unseasonable warmth for October; at 20 degrees C the month is already slamming down the gauntlet to the record-breaking September that has just preceded it as the wake-up call that humanity must finally heed, decades too late but still better late than never.

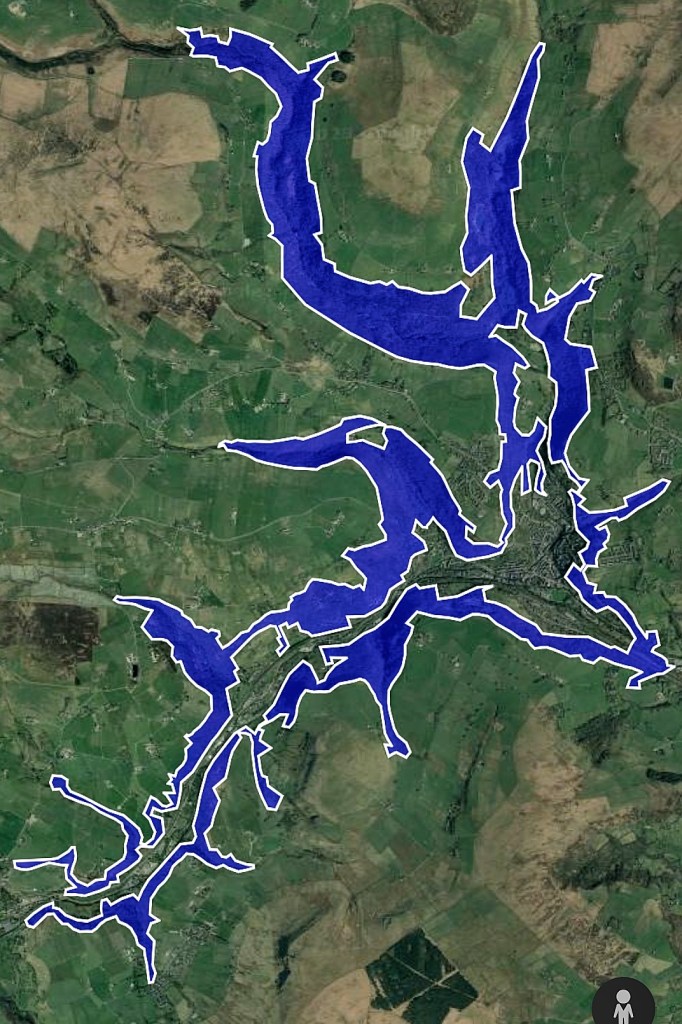

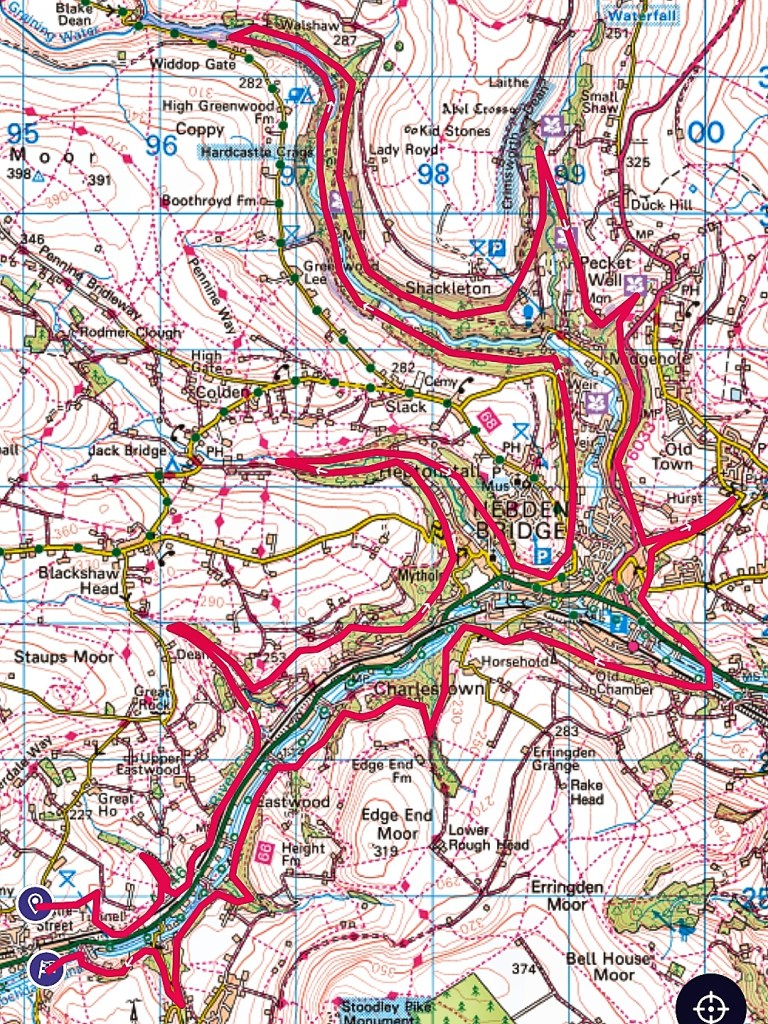

The quiet, largely unaided reforestation of these steep valley sides is the most significant landscape-scale change since the last days of the enclosures. This is not to say they were not wooded before this arboreal renaissance; in the mid-19th century, between Todmorden and Mytholmroyd, there were 62 named woodlands on either side of the Calder and within its tributary cloughs. But many of these were isolated from one another by intervening fields that had been cleared wherever less steep, less boulder-strewn areas of hillside proved more suitable for cultivation and pasture. But no longer: if one were to start at Woodhouse Mill Bridge on the outskirts of Todmorden and traverse the slopes on the north side of the valley all the way to Fallingroyd, and then cross the Calder and do the same on the south side back again, and delve into every clough – Ingham, Jumble Hole, Ibbot Royd, Beaumont, Stoodley, Shaw – and tributary valley – Colden, Hebden Dale, Crimsworth Dean – along the way, one could now walk for 22 miles without ever breaking from the shade of tree canopy. From Bean Hole Wood near Cross Stone to Horse Wood near Fallingroyd the river-cut slopes of the main Calder Valley are swaddled in oaks and beech, the former fields that once separated the older woods are now stocked with birch and willow, and every incised clough is crowded with rowan and sycamore and holly – all told, it is a 1500-acre near-continuous band of woodland.

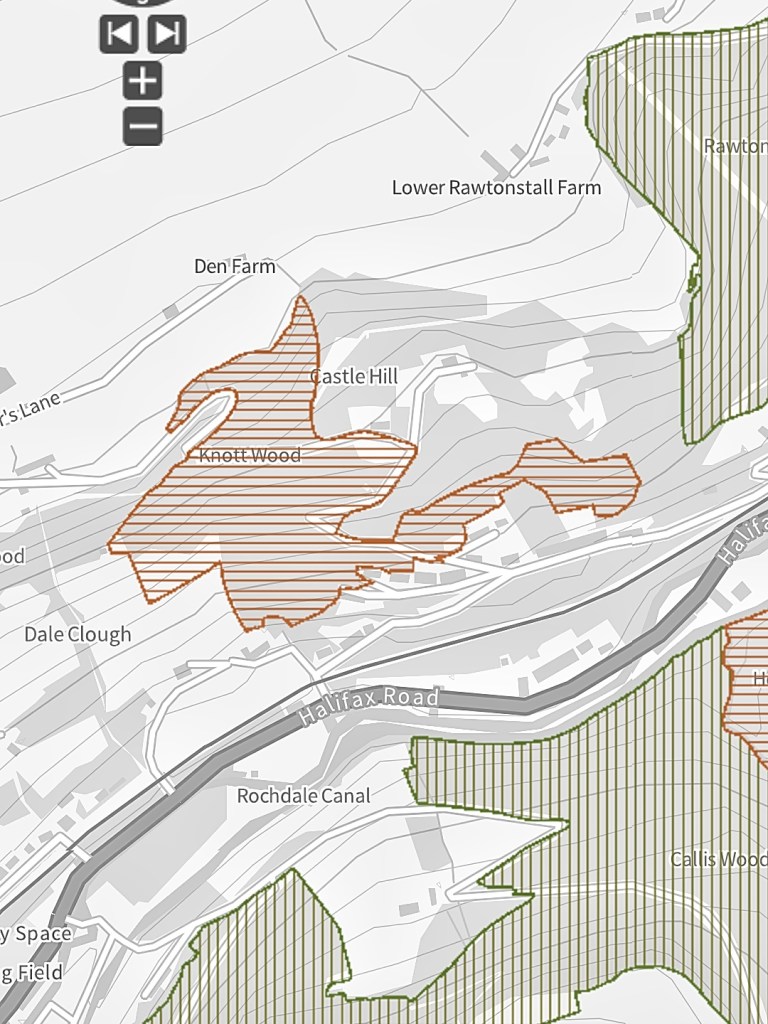

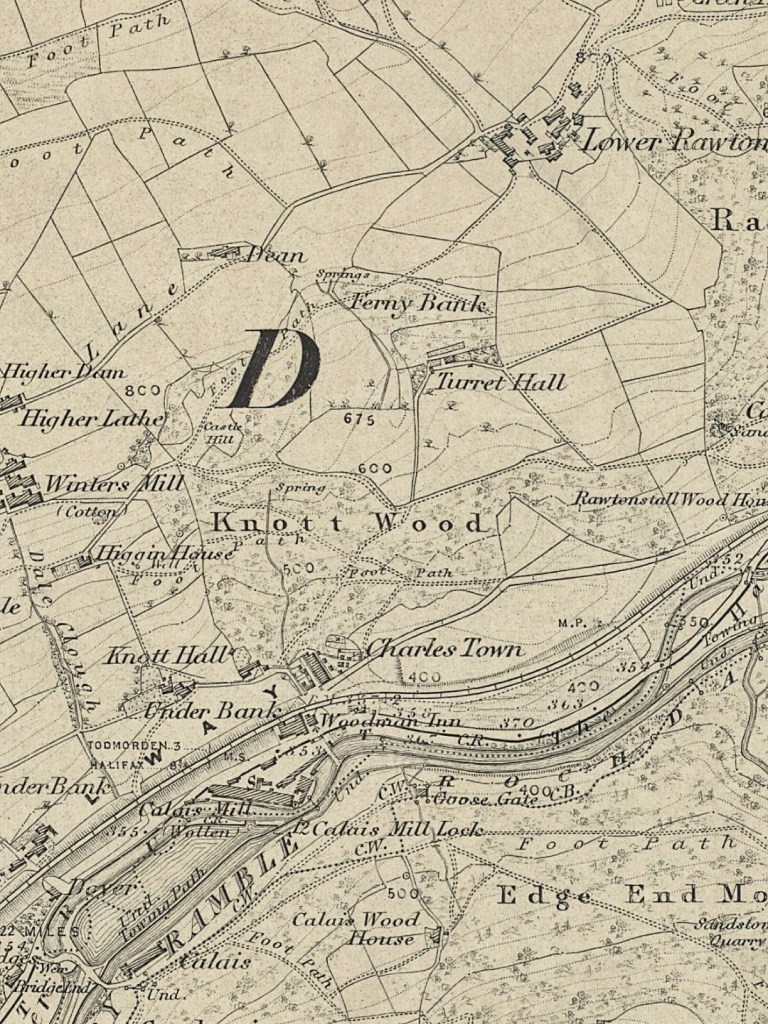

Knott Wood, which climbs the northern side of the valley above Charlestown, is a microcosm of these changes. If English Nature’s seminal 1980s Ancient Woodland Inventory survey is correct, it was once an isolated 20-acre woodland. Moreover, while its appearance on the resulting survey map means there is evidence that it has been continuously woodland since at least 1600 (the definition of ‘ancient’ woodland in the UK), it is not accorded the survey’s premier award of ‘Ancient and Semi-natural Woodland’, but the second-class stature of ‘Ancient Replanted Woodland’, meaning that when the Inventory was being compiled, there was some reason – perhaps the fact that it is not depicted on Jefferies’ 1775 map of Yorkshire, maybe that its magnificent oaks appear to all be of similar age – to believe that it had been cleared and replanted at some point in the last four centuries. From the assumed 17th- or 18th-century minimum size depicted on the AWI, by the time of the 1835 Myers map and the very first edition of the Ordnance Survey in 1851, it has extended a little along its top edge at Ferny Bank, but otherwise its shape and extent remains the same for the next century and more.

On its western side, Knott Wood was bounded by fields above Underbank House, built by the Horsfall family in the 1550s, and occupied (and rebuilt twice) by them over the next 400 years, until 1966. A 1774 estate map names the fields, Tenter Field and Well Field, that the wood borders, but the Horsfalls did benefit from a little spillage of the wood onto their land, six dayworks’ worth of ‘Spring Wood’, a local name for a coppice. But apart from this small section, the rest of Knott Wood was historically part of the vast Savile Estate, as was Turret Hall and its fields, which press down on the wood from above and keep it from ascending anywhere near as far up the hill in its eastern half, only allowing a tendril to curl above the terraces built along Oakville Road, the pre-turnpike route to Todmorden, until the final field of the estate – named Long Field on estate maps – reaches down to the road, severing Knott Wood from its neighbour, Rawtonstall Wood.

With the principal aim of capturing steam locomotives thundering around the infamous Charlestown Curve, a number of photographers recorded Knott Wood in the early decades of the 20th century from the Horsehold hillside opposite. A latticework of heavily-used footpaths can be seen under the oaks, as can the terraces and huts that occupied Long Field, evidently rented to the residents of Oakville Road for cultivation and poultry-keeping. Mr A. Sunderland, the resident of Turret Hall in 1943 (the Savile Estate sold it to Richard Greenwood in 1897, and his successor, Charles, sold it to the Sunderlands in 1924) when the inspector for the wartime National Farm Survey came calling, seemed to have little appetite to revive his pre-war poultry business and was now letting his neighbour up the hill at Lower Rawtonstall graze his animals on the fields in the summer, though he still kept 600 fowls. Similarly, Mr S.T. Horsfall at Underbank House provided little hope to the inspector of increasing his contribution towards feeding a beleaguered nation, with his 13 acres seeming to support all of four heifers, and cautioning in a hand-written note that ‘the land is very, very steep’, with any fertiliser which could improve productivity needing to be ‘carried up…in 56lb bags’. When the RAF flew over and photographed the valley in May 1948, there was scant evidence of any active farming at Underbank at all, though Mr Sunderland still seems to have at least some poultry, with bare earth around the sheds in Turret Hall’s enclosures – Old Hall Field, Meadow Field, Square Field, Steep Field and Turret Brink. This was still the case in the 1960s, with another photograph showing the sheds still in place and possibly still used, though Long Field has largely been abandoned and trees are starting to colonise and bridge the gap between Knott and Rawtonstall woods. By the 1990s, another aerial photo shows the sheds have gone, with Old Hall Field substantially turned to woodland, and Square Field, Steep Field and Turret Brink beginning to follow. Knott Wood’s liberation has finally arrived.

But unusually here, this woodland’s expansion was, in parts, assisted. Peter, the Sunderland’s successor at Turret Hall (long since called Wood Farm) after the 1970s, initially farmed the land, keeping chickens and pigs. But after retiring from these enterprises in the late-1980s, not only did he actively plant trees himself on half of Turret Brink, he also invited local conservation group Treesponsibility to traditionally manage the woodland for nature and community use. In the 1990s and early-2000s, they established areas of coppice, both within the existing core of ancient woodland, and by planting new hazel trees in Steep Field. They planted fruit trees in Meadow Field, and created new steps into and an encampment within the self-seeded young woods in Square Field for children’s Forest School activities. More recently, the lower half of Meadow Field has been more densely planted.

This planting has augmented the natural regeneration that filled in gaps beside Ferny Bank and on the site of the former commercial nurseries behind Beechwood View, where greenhouses were demolished in the 1960s; in the Horsfall’s Well Field and Tenter Field; and in Long Field, where John, the last of Oakville’s growers and poultry-keepers, still gazes up from the road and recalls it as his field. Taken together, all this means Knott Wood has more than doubled its size from 20 to 44 acres, and has joined with its neighbours of Marsh Wood and Rawtonstall Wood.

This is the story of how just one of the 62 woods between Todmorden and Mytholmroyd expanded and joined with its neighbours in the last century to help form the most extraordinary landscape feature of a nearly two-and-a-half-square-mile band of woodland in the Upper Calder Valley. Each of the woods that make it up have their own stories hidden in the leaf litter, to add to Knott Wood’s old walls and lost trackways and early-20th-century municipal tip and former fields overwhelmed by the new growth; its network of pipes and cisterns that brought water from the fields of Pry Farm down to the terraces that were built along its lower edge from the 1880s onwards; its charcoal burning platforms and ancient coppice stools and quarry at Castle Hill with myths of Saxon fortifications and a medieval moated manor house; its protection in 1946 by a Tree Preservation Order and later designation as a Local Wildlife Site; its new stories of use by Forest Schoolers and foragers, dog walkers and mountain bikers, bird conservationists and bee keepers; its revival of ancient woodland crafts by the Knott Wood Coppicers and Black Bark; and of course the extraordinary diversity of species it supports, with 380 found when the ecologist Charles Flynn surveyed it in 2009, including 153 species of plants, 131 of fungi, 33 species of birds and 10 of butterflies. The Calder Valley’s relationships with its woods, like the woodlands themselves, will continue to evolve.

Fascinating information. Thank you so much for doing this research and, just as importantly, distributing it, so that we can read about it. Some positive news is always welcome!!

LikeLike

Fascinating information. Thank you so much for doing this research and, just as importantly, distributing it, so that we can read about it. Some positive news is always welcome!!

LikeLike

Thank you, Stella.

LikeLike

Excellent combination of landscape photography and history.

LikeLike

Thank you, David. I’m looking forward to your HBLHS talk.

LikeLike

Fascinating read. Do you know where one might obtain a copy of the survey by Charles Flynn?

LikeLike

Thanks, Tom. I have a copy. If you email me (pauljamesknights@gmail.com) I’ll send you it.

LikeLike