Lapwings plunge and soar, their pitches and rolls so sudden it is as if they are caught in violent eddies of the air, freak vortexes that suck them in and swirl and spin them above the boggy, rush-filled pastures at the head of Hippins Clough. But they are in absolute control, their aerobatics ending every time with them alighted on the ground without a feather in their upswept crest out of place.

It is a shallow valley here, the string of farmhouses that straggles away from Blackshaw Head along the Long Causeway on one side, the dark slopes of Staups Moor, an island of ‘waste’ that escaped enclosure, on the other. Above Hippins Bridge, where the stream incises its way down the valley side to form Jumble Hole Clough, there have only ever been two dwellings close to the water in the valley bottom: Copley Holme, now a ruin and refused planning permission for an environmentally-sensitive renovation in 2016, and Daisy Bank, a permaculture smallholding hosting visitors in ‘rural retreat’ cabins.

The stream splits a little above where Earnshaw Water furtively joins it through a culvert, and on its southern, unnamed branch a tiny arch of stones forms a footbridge, its diminutive span impressive were it not for an even smaller one slightly downstream. The two tributaries above this fork are separated by a headland of heather, beset by heather beetles which have stripped its leaves to reveal the silvery stems, giving the moor a wan, sickly pallor. Hidden among the rushes, is the head of the Staups Moor Drain, a mile-long goit that curves on a contour around the moor to feed Staups Dam, which burst in 1896, its waters rushing down through Dean Bottom Farm to Jumble Hole Clough.

Across the old lane of Long Row, a cuckoo is pursued by two furious meadow pipits, one of the species it parasitises. It issues a single ‘cuck-oo’ and then its lesser-known hoarse, throaty cackle, a sound ripe for human interpretation as displaying an utter lack of compunction for what it was likely attempting to do at the pipits’ nest. From the pastures between the low ruin of Old White Reaps and (what was once New) White Reaps, thick with lambs, some playing together, others still finding their feet, comes the rusty pump song of the snipe.

Rosebay willowherb is emerging on the verges of Eastwood Road; a curlew draws a worm like spaghetti from the meadows surrounding Keelam, where children bounce on a trampoline on their school strike day off; and meadow pipits perch on the rocks among the quarries that pockmark the summit of Staups Moor. Over the other side of the intake wall, Jonathan’s silage meadows, first carved from the moor by the ‘encroachments’ of John Horsfall and subsequently privately purchased by him during the Stansfield Enclosure Act of 1815, are coming on nicely, all dandelions and daisies among the lush growing grass. Not every allotment awarded by the Act was used, however; bordering Cow Side Road, an ‘occupation road’, now just a track, constructed as part of this period of enclosure, there are awards to William Sutcliffe on the enclosure map that he never claimed and remain ‘unimproved’ moor to this day. On the other side of the road, two centuries after Henry Greenwood secured his 17 acres by act of parliament, one of the largest farmers in the district is intensively trying to improve the fertility of these fields, to the consternation of locals who noticed plastic waste – subsequently cleared – within the spread fertiliser in 2020.

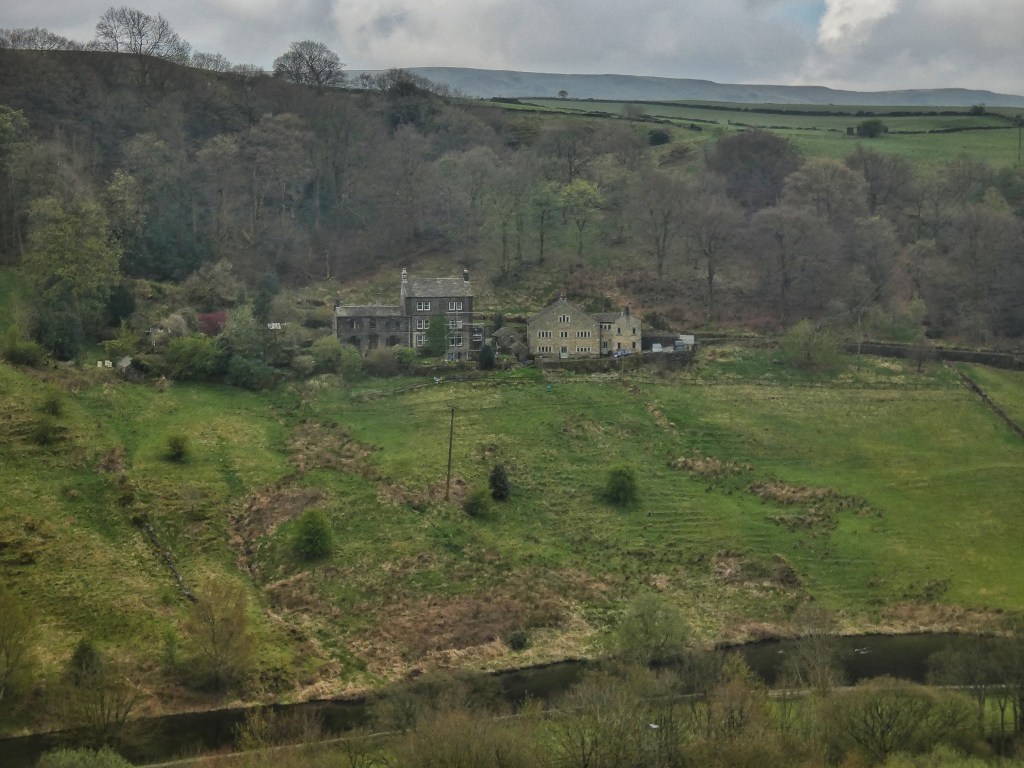

Across the stream at the finest yeoman’s farmhouse in the parish, the magnificent 17th-century Hippins, Tristan is hoisting its old stones to a roof by a pulley in the latest stage of the renovation of his childhood home. Up the causey stones, worn by water and feet into a shallow ‘U’, past the farm’s former barn, Betram and Lewis and their fellow alpacas at Apple Tree Farm are gathered, waiting while the routes along which visitors will lead them on walks are mown into their field.

Down the hill and days later, the renovation and conversion of the monumental barn and its attached cottage at Rodwell End is only just beginning, father and son wheelbarrowing out rubble and detritus. The barn’s cathedral-like interior is cool and dark, its stone arches soaring to the ceiling, its one remaining wooden cattle stall a reminder of its past. Along the lane at East Rodwell End, the 22 cherry trees in Mary’s garden are in bloom, their blossom thin now the trees are so old, petals just beginning to fall among the nettles and old glass bottles, a mistle thrush sadly singing on the wires behind the well, only adding to the melancholy.

But the brightness breaks through. Carpets of lesser celandine illuminate the confines of Rodwell Clough, and as the sun strengthens, its warmth rises off the precipitous slopes of Bean Hole Wood, a buzzard finding buoyancy on its currents. To travellers on Long Lane, teetering along the top edge of the wood, the uppermost trees, their roots just feet from the lane but already some way downhill, offer their flowers and fruits for an unusually close view into the canopy. At eye level are pine cones and willow catkins, rowan umbels readying to froth, an oak apple from last year with its resident wasp’s exit hole drilled underneath, and oak buds tentatively opening, hoping to avoid their fate in May 2020 when a late and vicious frost shrivelled and blackened the fresh leaves. Cow parsley and common sorrel, foxgloves and the furry tarantula legs of buckler ferns ready to spring from their comb fringe the lane. The beehives at Bean Hole Head are a bustle of activity.

Notwithstanding the usual hush of such places, the vast cemetery at Cross Stone is a forlorn place, with a battle evidently raging against the rhododendron, Japanese knotweed and bramble that threaten to swamp it. Closed to new burials in 2021, it is not clear that anything other than a full scale effort can save it from being consumed by such formidable opponents. Across the lane, an exceptional elder grows hard against its church, St Paul’s. Built in the 1830s with funds paid as an indemnity by France after the Napoleonic Wars, its slender tower, visible for miles around in its elevated position above Todmorden, belies the size of the body of the building, sunk into the hillside on a terrace. Long converted to a residence, under its shadow a neighbour, despairing at the unending task of holding her little flower bed’s ground against a yellow tide of dandelions that swells across the courtyard, recalls the bells ringing on its final day of service 45 years ago. The town has surged against the headland it perches on, but cannot quite reach it. There is a profusion of growth in the gardens that clamber up the valley side, a yew arch leading into one, a hazel coppice in another, and from under a tall, straggling privet hedge that has long since been freed from the usual zealous clipping that stunts its species, a sulphur-yellow brimstone butterfly launches itself into frantic flight.