The clatter of clogs, the ring of clashing swords and the cheers of hundreds of spectators echo around Weavers Square. In the centre of the medieval village of Heptonstall, as at every Good Friday, the Pace Egg play, a Calder Valley version of the traditional hero-combat British folk or mumming play, is being performed. Whether or not it can trace its roots back, as Victorian antiquarians claimed, to ancient Pagan spring ritual dramas of death and rebirth, the local tradition nonetheless has a significant lineage dating from at least the 18th century. The historian and naturalist W.B. Crump writes in The Little Hill Farm of still finding a performance in 1913 at the nearby village of Midgley, by which time others in the north of England had largely died out. After the First World War his colleague Henry William Harwood, together with the headteacher of Midgley School, revived performances, some of which were broadcast and televised by the BBC through the 1930s. A 1960 film held in the Yorkshire Film Archive shows that the tradition was still alive and well at that time, touchingly attended by Mr Harwood, then 75. A few years later, a pupil of Heptonstall School, David Burnop, and his school friends brought the tradition back to his village, and after a short gap he revived it again in 1979. Forty-four years later, under budding cherry and sycamore, beside the ruins of the 12th-century St Thomas a’ Becket Church, the cheer as he produces the bottle of Nip Nap to resurrect Bold Slasher, just vanquished by St George, is as loud as ever.

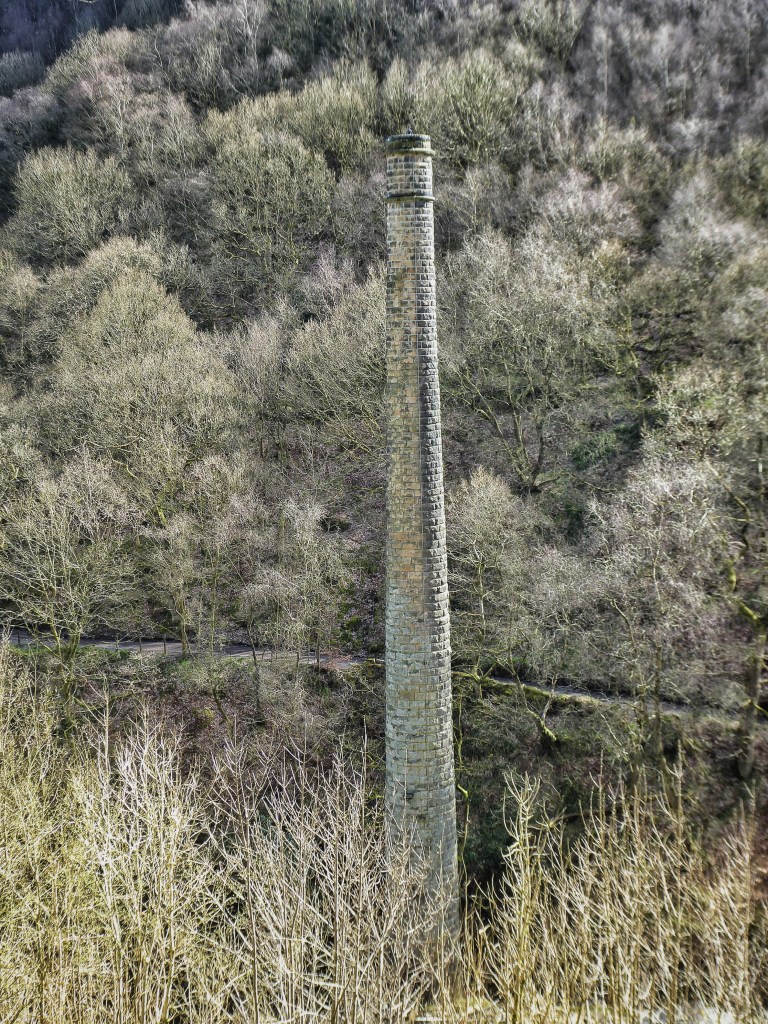

Heptonstall is perched on a peninsula, a headland created by the carvings of the Colden and Hebden waters. On the western, Colden side, the afternoon sun bakes the still leaf-bare Eaves Wood. Rising thermals bring spring scents of warming earth and a buzzard, spiralling and soaring into the sun. Larch, already out in their fresh baize green, bristle on the shoulder of Dill Scout’s Wood across the tributary valley. Below them, the weathered sandstone of the two chimneys of the Lumb Mills are the same colour as the trees they tower over. Crowds labour up the long ascent under the heather- and gorse-clad slope of The Whins, carrying jumpers in the sudden warmth as they head for the final, merriest performance of the day.

The morning of Easter Sunday is cold again, but the egg hunt on the village green is exciting enough for the eleven children taking part not to notice. The older ones tear about at breakneck speed, knowing all the likely places from years of experience, and knowing also to only take one egg from each nest, hidden in the crooks of willows, among the daffodils, at the base of the hazels that they planted two years ago, under the knots of buckler ferns about to unfurl the new season’s fronds. They even occasionally remember to go back and help the little ones trailing along in their wake. The warmth returns as the day goes on, and, in a sign of things to come, several of the egg hunters never go in and spend the entire day outside.

In Knott Wood, a block of ancient oak woodland on the northern slopes of the valley, the gas flames of the first bluebells are already alight, but a halt is put to further flarings by the return of single-figure temperatures. Greater stitchwort and wood sorrel flowers hang hunched in shame at having jumped the gun, and the wild garlic and lords-and-ladies’ leaves are glossed with rain. The waterfalls in Dale and Jumble Hole cloughs are in full voice after a meek late winter, a reminder not to take such tameness for granted as work continues to calm them in these conditions, the latest of which are willow revetments below Blackshaw Royd, constructed in recent weeks by Forus Tree.

But this whole hillside is wilding on its own; the bee-boled terraces of Beverley End are a riot of ramsons, the cemetery of Mount Olivet, its chapel long gone, has not had a burial since 1932, willows are prising apart what is left of Higgin House, and the fields named on the 1774 estate map of Underbank House – Long Pasture, Well Field, Orchard Field, Great Pinhill – are now overtaken by oak saplings and bramble. It is 30 years since John was the last of generations to keep chickens and grow vegetables on terraces which are now clothed in bluebells under maturing woodland. A roe buck, its antlers sheathed in velvet it will never thrash off on the nearby rowan that has been stripped in the past, lies newly dead under the hollowed-out bower of holly that has grown back in the century since photographs show the oaks with no understory to speak of. The paths of its kin show as much use as the human paths they cross. The bathtub in Peter’s old pig field is seething with tadpoles, and the tracks he used to drive his tractor down grow every year narrower as the leaf litter banks up against the crumbling walls.