Storm Larisa blusters all day, the swirl of snow impressive, yet it’s all to little effect: at last light there is disappointment among the would-be sledgers at the meagre covering of snow on the village green. But after dark it redoubles its efforts, raging all night. School closure notices are sent out at dawn, and the neighbourhood children are building snowmen fully an hour before the normal school run time, remaining out for nine hours. Their joyful screams are answered by the calls of a flock of 10 curlews sailing overhead.

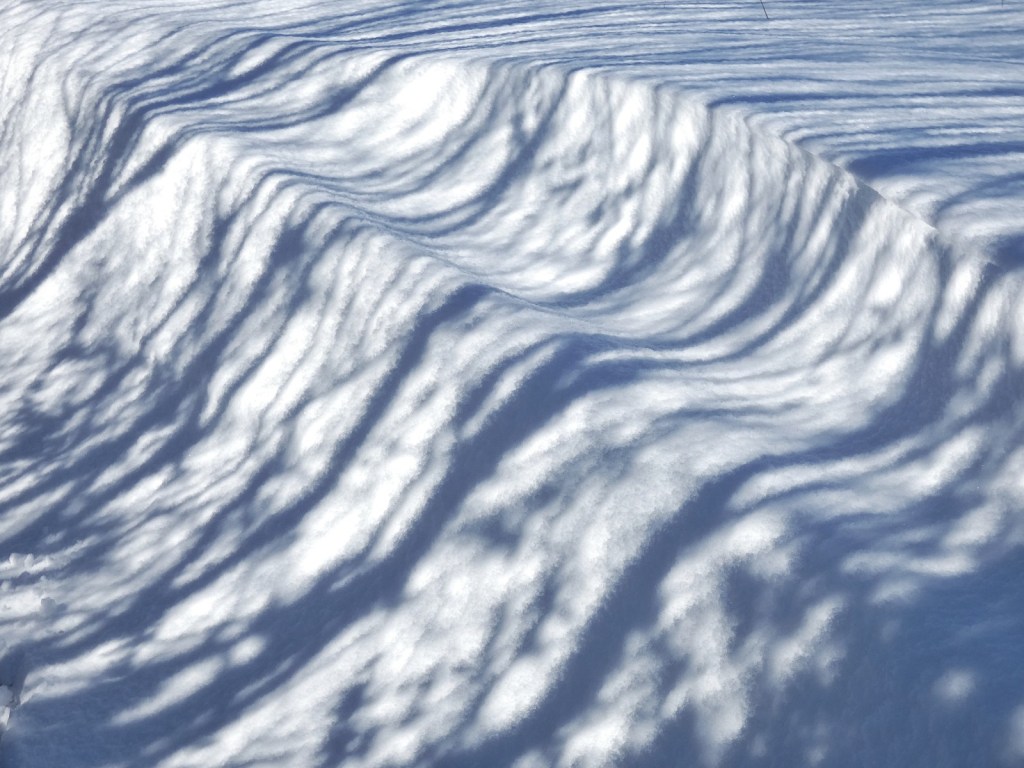

In the woods, the plastered hollies are bent low over the paths, but they are soon unburdening themselves of the weight they carry; as the warmth of the sun asserts itself through the morning, there is the slap, pat and slump of snow sliding off branches. Slender tree shadows drape themselves over the drifts on Dark Lane, and the sheep leave mazy tracks in the Home Field at Edge End Farm where the hay has been brought out.

By dusk, the village green is substantially living up to its name and the south-facing valley side woods have been thoroughly defrosted, but opposite, the Callis Wood birches retain the smothering on their north-east-facing side, and the old zig-zagging avenue of Foster’s Rake is still deep in trackless snow. The drifts at Cruttonstall are the deepest since 2010’s Big Freeze, and as soon as the sun slips behind the Bride Stones the temperature begins its spectacular 10 degree plunge.

Thirty-six hours after this nadir, it is 21 degrees warmer and the snow has all but vanished. The melt has half-filled the rivers, leaving uncomfortably little room for a day of torrential rain, but Calder Valley residents have learnt that there is rain and then there is rain, and this band’s limited effect on river levels is as welcome as Storm Larisa’s first day of snow was disappointing. A mink thinks nothing of any of it, slinking along the canal as voraciously curious as always, gliding along close to the bank opposite the towpath, craning into every cranny, nipping into and out of nooks, diving under the Stubbing bridge and emerging with a fish to crunch.

The temperature plummets again. The resident pair of goosanders glide downstream on the river’s swift current, but then somehow anchor midstream between the Station Road bridge and the weir, and after a little light preening, tuck their bills into the wing feathers folded on their backs and doze, oblivious to the blizzard that capriciously arrives in defiance of the Met Office’s assurance of a morning of unbroken sun. The newly-dug ponds at one side of High Hirst Woodmeadow reflect the blank sky and ripple in the winds, and in its maturing woodland on the other side, the hazel catkins, browning now but some still fresh and green, shake and wriggle like so many suspended caterpillars. Their tiny flowers on the end of their leaf buds are almost all shrivelled and spent, but a few of their little scarlet tongues remain.

The snow returns yet again the following morning. The bogs and puddles on Flaight Hill, where the farmers of Crimsworth Dean and Pecket Well once cut peat for their fires, are frozen and rimed. But a skylark is singing of drowsy summer days up in the cloud that bears down on the moorland plateau, and curlews, lapwings and golden plover, too, are far from convinced that this amounts to a slamming shut of spring’s door. It is no more than a brief pause on the threshold, they sing. And they are not wrong; a couple of hours later, the morning’s snow has vanished, leaving only the remnants of last week’s drifts in the seven crumpled and canyoned acres of Delph End Quarry.

It is difficult to imagine the clamour that cleaving these moors apart would have created, but in the late-1860s there was yet more upheaval when John F. Bateman arrived nearby to sink a ventilation shaft. This superstar engineer’s task was to dam the Widdop Water for the burgeoning population and industry of Halifax, but that he was also able to devise a route for its waters to flow through eight miles of tortuous terrain – clough after moorland plateau after clough – using gravity alone, is nothing short of a marvel. After five and a half meandering miles along the north side of the Graining Water and Hebden Water, it takes a 300-foot plunge down to an aqueduct disguised as a bridge across Crimsworth Dean Beck, before launching an equal height up the other side by means of the syphon effect. Snaking its way into Pecket Well Clough, it then disappears into the Castle Carr Tunnel under Wadsworth Moor for a mile and a half, before crossing the top of Luddenden and eventually completing its nine-and-a-half-mile journey at Ramsden Wood Reservoir. The Castle Carr Tunnel needed three ventilation shafts. This first one is nearly 400 feet deep, and from its grated windows comes the same sound it has issued for a century and a half – the rush of water from deep within the moor. But the sound is an aural illusion, perhaps as a result of the depth and echo having an amplifying effect on how swiftly it sounds like the water is speeding, for it is actually moving no faster than one mile per hour, the decline of the conduit being so slight, losing no more than 30 feet of height across its nine-and-a-half-mile course. The hare that sprints away from it, though, more than matches its sound, scattering startled sheep as it bolts through the rushes.

I’ve just found out that one of my ancestors was born at Marsh farm in 1848. He had the most amazing name: George Frederick Handel Halstead. As a musician myself it was his name that attracted me to finding out more about him!

LikeLike

Marsh Farm is one of my favourite farms to photograph, both from this vantage and from the other side of the valley. I’ll look forward to reading about this extraordinarily-named individual, Heather.

LikeLike