We brought along a best friend of my son’s on one of our walks over the summer. It made for a very different experience for the both of us. For him, the walk was essentially turned into a mobile version of the hours of play that they usually spend on our local green. For myself, I spent much more time than I usually would observing and listening to their play, and walking alongside them for hours while they kept up a constant stream of imaginative play – building worlds out of the dark rocks and wizened hawthorns we passed and inventing elaborate characters to inhabit the strange hybrid reality they created – made for a fascinating experience.

My imaginative powers evidently being greatly diminished as an adult, I could not join in their play to any great extent, but I am glad I was able to lead them through a landscape that proved fertile ground for their play, for we did not compromise on our usual habit of tramping the wilder, less frequented paths, with an ascent of Foster’s Rake to the Domesday settlement of Cruttonstall and its crumbling 17th century farmhouse, before mounting the muscular shoulder of Lodge Hill and bullying down through the rushes of Edge End Moor to Lower Rough Head.

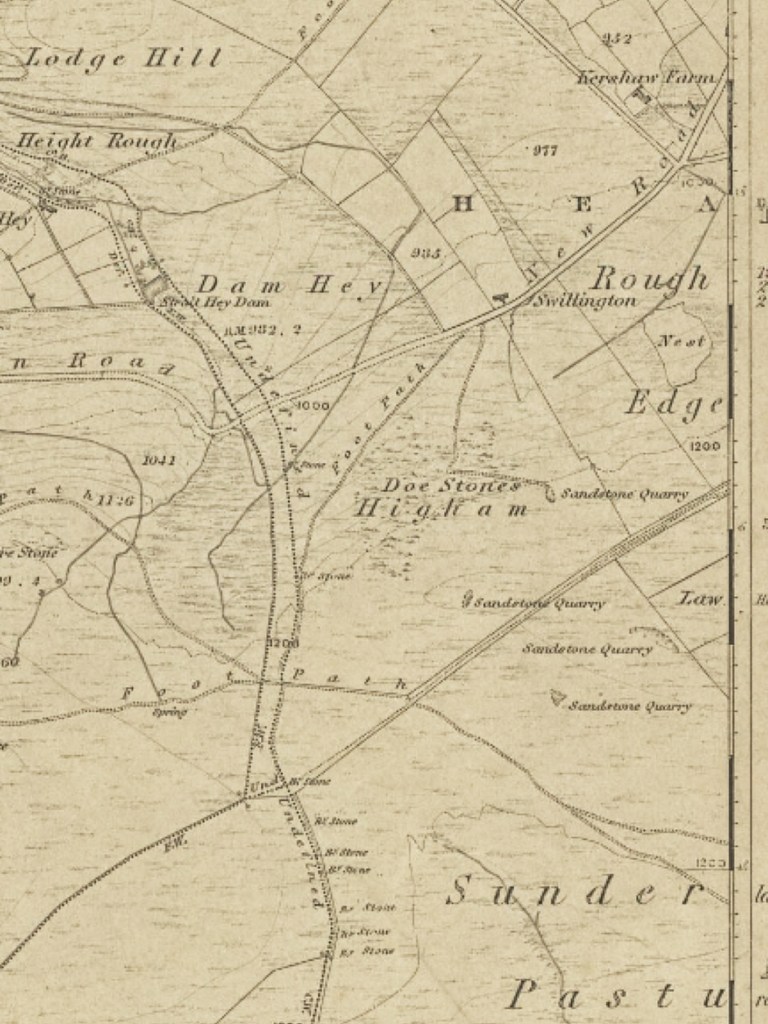

After a peer down the gurgling field drain that funnels the stream to Beaumont Clough and a lunch break sitting on an enormous prostrate gate stoop in Pinnacle Lane, we took to a right of way that I think must be one of the least used in the whole valley. There is simply no need for anyone to want to ascend the rush-choked, boggy, pathless rise of Rough Edge from Swillington to the site of the vanished house at Johnny’s Gap, since both ends of the route are served by good tracks. But I had spotted something intriguing on the mid-19th-century OS map that made me want to take this route: a very irregularly-shaped, one-and-a-half-acre enclosure that is granted its own name, Nest. I know of no other like it, either in shape or in the stature apparently accorded it by being named.

Once we had fought our way through rush and bog and up the slope to its top edge and picked out its fallen walls, now almost invisible under grass and moss and bilberry, its former purpose was no more clear. At least, that is, it was not clear to me – the boys were in no doubt it was for rearing dragons and must immediately be reconstructed. They set about this urgent task with some gusto, hauling stones about so large that I had to cover my eyes.

After having given free reign to their enthusiasm for as long as I dared, before there was a crushed finger to nurse I moved us on to Johnny’s Gap and through two failed experiments to bring order and productivity to the moor: Christopher Rawson’s grid of shattered enclosures and vanished farms, and the muffled hush of Sunderland Pasture’s conifer plantation, destined, it seems, never to be harvested. In here, they spooked themselves by telling ghost stories while squinting into the deep, dead shadows that pressed on either side, and we burst with relief back into the wide spaces of the moor.

I only allowed them a few yards on the easy, well-trodden path from Stoodley Pike before plunging us off it and down one of the few remaining stretches of the 14th-century Erringden Deer Park’s ditch-and-bank boundary, at the bottom of which we found an enormous horned sheep’s skull, which they agreed to share custody of. They kept up their uninterrupted stream of chatter the entire way round, moving seamlessly from exchanging designs for new Star Wars spaceships to finding geocaches (one on Pinnacle Lane and one at Johnny’s Gap), from crouching and examining little caves under rocks to inventing gnome-like characters to live in them, complete with the attire they would wear and the weapons they would carry.

Back on our street, while I was more than ready for a sit down after this six-hour, seven-mile walk, all they wanted to do was get their cloaks on (Hogwarts for my son, Jedi for his friend) and carry on their play on the green, which they did until finally called in for dinner.